Books

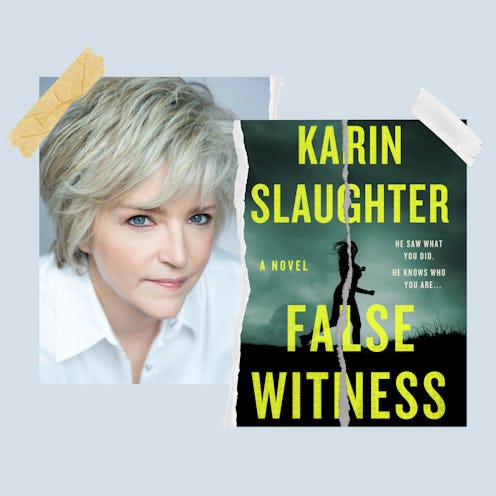

Karin Slaughter’s False Witness Is Out Next Month — But You Can Start Reading It Now

Get a peek at an exclusive excerpt — and check back over the next two weeks for further installments.

Karin Slaughter’s much-anticipated fifth standalone novel — her 21st overall — is almost here. Set to hit stores on July 20, False Witness centers on Leigh Collier, a lawyer who has built a stable career and a safe home for her teenage daughter, Maddy — until her past catches up with her, and threatens to ruin everything. Leigh has no choice but to turn to her kid sister, Callie, for assistance, even if it means unearthing skeletons in both of their closets.

Bustle is excited to publish an exclusive excerpt from False Witness below, and to announce two subsequent sneak peeks, going live on June 22 and 29. Check back for each installment, and read up to the novel’s fifth chapter — before the book is even released.

Keep scrolling for your first look at the prologue and first chapter from Karin Slaughter’s False Witness — out from William Morrow next month, and available for preorder now. (Update: the second excerpt, featuring Chapters 2 and 3, is now live as well.)

Trigger Warning: This piece contains descriptions of sexual assault, child sexual abuse, and the production of child sexual abuse materials.

Summer 1998

From the kitchen, Callie heard Trevor tapping his fingers on the aquarium. Her grip tightened around the spatula she was using to mix cookie dough. He was only ten years old. She thought he was being bullied at school. His father was an asshole. He was allergic to cats and terrified of dogs. Any shrink would tell you the kid was terrorizing the poor fish in a desperate bid for attention, but Callie was barely holding on by her fingernails.

Tap-tap-tap.

She rubbed her temples, trying to ward off a headache. “Trev, are you tapping on the aquarium like I told you not to?”

The tapping stopped. “No, ma’am.”

“Are you sure?”

Silence.

Callie plopped dough onto the cookie sheet. The tapping resumed like a metronome. She plopped out more rows on the three count.

Tap-tap-plop. Tap-tap-plop.

Callie was closing the oven door when Trevor suddenly appeared behind her like a serial killer. He threw his arms around her, saying, “I love you.”

She held on to him as tightly as he held on to her. The fist of tension loosened its grip on her skull. She kissed the top of Trevor’s head. He tasted salty from the festering heat. He was standing completely still, but his nervous energy reminded her of a coiled spring. “Do you want to lick the bowl?”

The question was answered before she could finish asking it.

He dragged a kitchen chair to the counter and made like Pooh Bear sticking his head into a honeypot.

Callie wiped the sweat from her forehead. The sun had gone down an hour ago, but the house was still broiling. The air conditioning was barely functioning. The oven had turned the kitchen into a sauna. Everything felt sticky and wet, herself and Trevor included.

She turned on the faucet. The cold water was irresistible. She splashed her face, then, to Trevor’s delight, sprinkled some on the back of his neck.

Once the giggling died down, Callie adjusted the water to clean the spatula. She placed it in the drying rack beside the remnants from dinner. Two plates. Two glasses. Two forks. One knife to cut Trevor’s hot dog into pieces. One teaspoon for a dollop of Worcestershire sauce mixed in with the ketchup.

Trevor handed her the bowl to wash. His lips curved up to the left when he smiled, the same way his father’s did. He stood beside her at the sink, his hip pressing against her.

She asked, “Were you tapping the glass on the aquarium?”

He looked up. She caught the flash of scheming in his eyes. Exactly like his father. “You said they were starter fish. That they probably wouldn’t live.”

She felt a nasty response worthy of her mother press against the back of her clenched teeth — Your grandfather’s going to die, too. Should we go down to the nursing home and stick needles under his fingernails?

Callie hadn’t said the words out loud, but the spring inside of Trevor coiled even tighter. She was always unsettled by how tuned in he was to her emotions.

“Okay.” She dried her hands on her shorts, nodding toward the aquarium. “We should find out their names.”

He looked guarded, always afraid of being the last one to get the joke. “Fish don’t have names.”

“Of course they do, silly. They don’t just meet each other on the first day of school and say, ‘Hello, my name is Fish.’” She gently nudged him into the living room. The two bicolored blennies were swimming a nervous loop around the aquarium. She had lost Trevor’s interest several times during the arduous process of setting up the saltwater tank. The arrival of the fish had sharpened his focus to the head of a pin.

Callie’s knee popped as she knelt down in front of the aquarium. The throbbing pain was more tolerable than the sight of Trevor’s grimy fingerprints clouding the glass. “What about the little guy?” She pointed to the smaller of the two. “What’s his name?”

Trevor’s lips curved up at the left as he fought a smile. “Bait.”

“Bait?”

“For when the sharks come and eat him!” Trevor burst into too-loud laughter, rolling on the floor at the hilarity.

Callie tried to rub the throb out of her knee. She glanced around the room with her usual sinking depression. The stained shag carpet had been flattened sometime in the late eighties. Streetlight lasered around the puckered edges of the orange and brown drapes. One corner of the room was taken up by a fully stocked bar with a smoky mirror behind it. Glasses hung down from a ceiling rack and four leather bar stools crowded around the L-shape of the sticky wooden top. The entire room was centered around a giant television that weighed more than Callie. The orange couch had two depressing his-and-her indentations on opposite ends. The tan club chairs had sweat stains at the backs. The arms had been burned by smoldering cigarettes.

Trevor’s hand slipped inside of hers. He had picked up on her mood again.

He tried, “What about the other fish?”

She smiled as she rested her head against his. “How about...” She cast around for something good — Anne Chovey, Genghis Karp, Brine Austin Green. “Mr. Dar-Sea?”

Trevor wrinkled his nose. Not an Austen fan. “What time is Dad getting home?”

Buddy Waleski got home whenever he damn well got home. “Soon.”

“Are the cookies ready yet?”

Callie winced her way to standing so she could follow him back into the kitchen. They watched the cookies through the oven door. “Not quite, but when you’re out of your bath —”

Trevor bolted down the hallway. The bathroom door slammed.

She heard the faucet squeak. Water splattered into the tub. He started humming.

An amateur would claim victory, but Callie was no amateur. She waited a few minutes, then cracked open the bathroom door to make sure he was actually in the tub. She caught him just as he dipped his head under the water.

Still not a win — there was no soap in sight — but she was exhausted and her back ached and her knee was pinching when she walked up the hallway so all she could do was grit through the pain until she reached the bar and filled a martini glass with equal parts Sprite and Captain Morgan.

Callie limited herself to two swigs before she leaned down and checked for blinking lights under the bar. She had discovered the digital camera by accident a few months ago. The power had gone out. She’d been looking for the emergency candles when she noticed a flash out of the corner of her eye.

Callie’s first thought had been — sprained back, trick knee, and now her retina was detaching — but the light was red, not white, and it was flashing like Rudolph’s nose between two of the heavy leather stools under the bar. She had pulled them away. Watched the red light flash off the brass foot rail that stringed along the bottom.

It was a good hiding place. The front of the bar was done up in a multi-colored mosaic. Shards of mirror punctuated broken pieces of blue, green, and orange tile, all of which obscured the one-inch hole cut through to the shelves in the back. She’d found the Canon digital camcorder behind a cardboard box filled with wine corks. Buddy had taped the power cord up inside the shelf to hide it, but the power had been off for hours. The battery was dying. Callie had no idea whether or not the camera had been recording. It was pointed directly at the couch.

This is what Callie had told herself: Buddy had friends over almost every weekend. They watched basketball or football or baseball and they talked bullshit and business and women, and they probably said things that gave Buddy leverage, the kind of leverage that he could later use to close a deal, and probably that’s what the camera was for.

Probably.

She left out the Sprite on her second drink. The spiced rum burned up her throat and into her nose. Callie sneezed, catching most of it with the back of her arm. She was too tired to get a paper towel from the kitchen. She used one of the bar towels to wipe off the snot. The monogrammed crest scratched her skin. Callie looked at the logo, which summed up Buddy in a nutshell. Not the Atlanta Falcons. Not the Georgia Bulldogs. Not even Georgia Tech. Buddy Waleski had chosen to be a booster for the division two Bellwood Eagles, a high school team that went zero-to-ten last season.

Big fish/small pond.

Callie was downing the rest of the rum when Trevor came back into the living room. He wrapped his skinny arms around her again. She kissed the top of his head. He still tasted sweaty, but she had fought enough battles for the day. All she wanted now was for him to go to sleep so that she could drink away the aches and pains in her body.

They sat on the floor in front of the aquarium as they waited for the cookies to cool down. Callie told him about her first aquarium. The mistakes she had made. The responsibility and care it took to keep the fish thriving. Trevor had turned docile. She told herself it was because of the warm bath and not because of the way the light went out of his eyes every time he saw her standing behind the bar pouring herself another drink.

Callie’s guilt started to dissipate as they got closer to Trevor’s bedtime. She could feel him start to wind himself up as they sat at the kitchen table. The routine was familiar: An argument about how many cookies he could eat. Spilled milk. Another cookie argument. A discussion about which bed he would sleep in. A struggle to get him into his pajamas. A negotiation over how many pages she would read from his book. A kiss goodnight. Another kiss goodnight. A request for a glass of water. Not that glass, this glass. Not this water, that water. Screaming. Crying. More battling. More negotiating. Promises for tomorrow — games, the zoo, a visit to the water park. And so on and so on until she eventually, finally, found herself standing alone behind the bar again.

She stopped herself from rushing to open the bottle like a desperate drunk. Her hands were shaking. She watched them tremor in the silence of the dingy room. More than anything else, she associated the room with Buddy. The air was stifling. Smoke from thousands of cigarettes and cigarillos had stained the low ceiling. Even the spiderwebs in the corners were orangey-brown. She never took her shoes off inside the house because the feel of the sticky carpet cupping her feet made her stomach turn.

Callie slowly twisted the cap off the bottle of rum. The spices tickled at her nose again. Her mouth started to water from anticipation. She could feel the numbing effects just from thinking about the third drink, not the last drink, the drink that would help her shoulders relax, her back stop spasming, her knee stop throbbing.

The kitchen door popped open. Buddy coughed, the phlegm tight in his throat. He threw his briefcase onto the counter. Kicked Trevor’s chair back under the table. Snatched up a handful of cookies. Held his cigarillo in one hand as he chewed with his mouth open. Callie could practically hear the crumbs pinging off the table, bouncing against his scuffed shoes, scattering across the linoleum, tiny cymbals clanging together, because everywhere Buddy went, there was noise, noise, noise.

He finally noticed her. She had that early feeling of being glad to see him, of expecting him to envelop her in his arms and make her feel special again. Then more crumbs dropped from his mouth. “Pour me one, baby doll.”

She filled a glass with Scotch and soda. The stink of his cigarillo wafted across the room. Black & Mild. She had never seen him without a box sticking out of his shirt pocket.

Buddy was finishing the last two cookies as he pounded his way toward the bar. Heavy footsteps creaking the floors. Crumbs on the carpet. Crumbs on his wrinkled, sweat-stained work shirt. Trapped in the stubble of his five o’clock shadow.

Buddy was six-three when he stood up straight, which was never. His skin was perpetually red. He had more hair than most men his age, a little bit of it starting to gray. He worked out, but only with weights, so he looked more gorilla than man — short-waisted, with arms so muscled that they wouldn’t go flat to his sides. Callie seldom saw his hands when they weren’t fisted.

Everything about him screamed ruthless motherfucker. People turned in the opposite direction when they saw him in the street.

If Trevor was a coiled spring, Buddy was a sledgehammer. He dropped the cigarillo into the ashtray, slurped down the Scotch, then banged the glass down on the counter. “You have a good day, dolly?”

“Sure.” She stepped aside so he could get a refill.

“I had a great one. You know that new strip mall over on Stewart? Guess who’s gonna be doing the framing?”

“You,” Callie said, though Buddy hadn’t waited for her to answer.

“Got the down payment today. They’re pouring the foundation tomorrow. Nothing better than having cash in your pocket, right?” He belched, pounding his chest to get it out. “Fetch me some ice, will ya?”

She started to go, but his hand grabbed her ass like he was turning a doorknob.

“Lookit that tiny little thing.”

There had been a time early on when Callie had thought it was funny how obsessed he was with her petite size. He would lift her up with one arm, or marvel at his hand stretched across her back, the thumb and fingers almost touching the edges of her hip bones. He called her little bit and baby girl and doll and now...

It was just one more thing about him that annoyed her.

Callie hugged the ice bucket to her stomach as she headed toward the kitchen. She glanced at the aquarium. The blennies had calmed down. They were swimming through the bubbles from the filter. She filled the bucket with ice that smelled like Arm & Hammer baking soda and freezer-burned meat.

Buddy swiveled around in his bar stool as she made her way back toward him. He had pinched off the tip of his cigarillo and was shoving it back into the box. “God damn, little girl, I love watching your hips move. Do a spin for me.”

She felt her eyes roll again — not at him, but at herself, because a tiny, stupid, lonely part of Callie still bought into his flirting. He was honest-to-God the first person in her life who had ever made her feel truly loved. She had never before felt special, chosen, like she was all that mattered to another human being. Buddy had made her feel safe and cared for.

But lately, all he wanted to do was fuck her.

Buddy pocketed the Black & Milds. He jammed his paw into the ice bucket. She saw dirt crescents under his fingernails.

He asked, “How’s the kid?”

“Sleeping.”

His hand was cupped between her legs before she caught the glint in his eye. Her knees bowed awkwardly. It was like sitting on the flat end of a shovel.

“Buddy —”

His other hand clamped around her ass, trapping her between his bulging arms. “Look at how tiny you are. I could stick you in my pocket and nobody’d ever know you were there.”

She could taste cookies and Scotch and tobacco when his tongue slid into her mouth. Callie returned the kiss because pushing him away, bruising his ego, would take up so much time and end up with her back at the exact same damn place.

For all his sound and fury, Buddy was a pussy when it came to his feelings. He could beat a grown man to a pulp without blinking an eye, but with Callie, he was so raw sometimes that it made her skin crawl. She had spent hours reassuring him, coddling him, propping him up, listening to his insecurities roll in like an ocean wave scratching at the sand.

Why was she with him? She should find someone else. She was out of his league. Too pretty. Too young. Too smart. Too classy. Why did she give a stupid brute like him the time of day? What did she see in him — no, tell him in detail, right now, what exactly was it that she liked about him? Be specific.

He constantly told her she was beautiful. He took her to nice restaurants, upscale hotels. He bought her jewelry and expensive clothes and gave her mother cash when she was short. He would beat down any man who even thought about looking at her the wrong way. The outside world would probably think that Callie had landed like a pig in shit, but, inside, she wondered if she’d be better off if he was as cruel to her as he was to everyone else. At least then she’d have a reason to hate him. Something real that she could point to instead of his pathetic tears soaking her shirt or the sight of him on his knees begging for her forgiveness.

“Daddy?”

Callie shuddered at the sound of Trevor’s voice. He stood in the hallway clutching his blanket.

Buddy’s hands kept Callie locked in place. “Go back to bed, son.”

“I want Mommy.”

Callie closed her eyes so she wouldn’t have to see Trevor’s face. “Do as I say,” Buddy warned. “Now.”

She held her breath, only letting it go when she heard the slow pad of Trevor’s feet back down the hall. His bedroom door creaked on its hinges. She heard the latch click.

Callie pulled away. She walked behind the bar, started turning the labels on the bottles, wiping down the counter, pretending like she wasn’t trying to put an obstacle between them.

Buddy huffed a laugh, rubbing his arms like it wasn’t sweltering in this wretched house. “Why’s it so cold all a sudden?”

Callie said, “I should go check on him.”

“Nah.” Buddy came around the bar, blocking her exit. “Check on me first.”

Buddy guided her palm to the bulge in his pants. He moved her hand up and down, once, and she was reminded of watching him jerk the rope on the lawnmower to start the motor.

“Like that.” He repeated the motion. Callie relented. She always relented. “That’s good.”

Callie closed her eyes. She could smell the pinched-off tip of his cigarillo still smoldering in the ashtray. The aquarium gurgled from across the room. She tried to think of some good fish names for Trevor tomorrow.

James Pond. Darth Baiter. Tank Sinatra.

“Jesus, your hands are so small.” Buddy unzipped his pants. Pressed down on her shoulder. The carpet behind the bar felt wet. Her knees sucked into the shag. “You’re my little ballerina.”

Callie put her mouth on him.

“Christ.” Buddy’s grip was firm on her shoulder. “That’s good. Like that.”

Callie squeezed her eyes closed.

Tuna Turner. Leonardo DeCarpio. Mary Kate and Ashley

Ocean.

Buddy patted her shoulder. “Come on, baby. Let’s finish on the couch.”

Callie didn’t want to go to the couch. She wanted to finish now. To go away. To be by herself. To take a breath and fill her lungs with anything but him.

“God dammit!” Callie cringed.

He wasn’t yelling at her.

She could tell from the shift in the air that Trevor was back in the hallway. She tried to imagine what he’d seen. One of Buddy’s meaty hands gripping the counter, his hips thrusting at something underneath the bar.

“Daddy?” he asked. “Where did —”

“What did I tell you?” Buddy bellowed. “I’m not sleepy.”

“Then go drink your medicine. Go.”

Callie looked up at Buddy. He was jamming one of his fat fingers toward the kitchen.

She heard Trevor’s chair screech across the linoleum. The back banging against the counter. The cabinet creaking open. A tick-tick-tick as Trevor turned the childproof cap on the NyQuil. Buddy called it his sleepy medicine. The antihistamines would knock him out for the rest of the night.

“Drink it,” Buddy ordered.

Callie thought of the delicate ripples in Trevor’s throat when he threw his head back and gulped down his milk.

“Leave it on the counter,” Buddy said. “Go back to your room.”

“But I —”

“Go back to your damn room and stay there before I beat the skin off your ass.”

Again, Callie held her breath until she heard the click of Trevor’s bedroom door latching closed.

“Fucking kid.”

“Buddy, maybe I should —”

She stood up just as Buddy swung back around. His elbow accidentally caught her square in the nose. The sudden crack of breaking bones split her like a bolt of lightning. She was too stunned to even blink.

Buddy looked horrified. “Doll? Are you okay? I’m sorry, I —” Callie’s senses toggled back on one by one. Sound rushing into her ears. Pain flooding her nerves. Vision swimming. Mouth filling with blood.

She gasped for air. Blood sucked down her throat. The room started spinning. She was going to pass out. Her knees buckled. She frantically grabbed at anything to keep from falling. The cardboard box toppled from the shelf. The back of her head popped against the floor. Wine corks hit her chest and face like fat drops of rain. She blinked up at the ceiling. She saw the bicolored fish swimming furiously in front of her eyes. She blinked again. The fish darted away. Breath swirled inside of her lungs. Her head started pounding along with her heartbeat. She wiped something off her chest. The box of Black & Mild had fallen out of Buddy’s shirt pocket, scattering the slim cigarillos across her body. She craned her neck to find him.

Callie had expected Buddy to have that apologetic puppy-dog look on his face, but he barely noticed her. He was holding the video camera in his hands. She’d accidentally pulled it off the shelf along with the box. A chunk of plastic had chipped off the corner.

He let out a low, sharp, “Shit.”

Finally, he looked at her. His eyes went shifty, the same way Trevor’s did. Caught red-handed. Desperate for a way out.

Callie’s head fell back against the carpet. She was still so disoriented. Everything she looked at pulsed along with the throb inside her skull. The glasses hanging down from the rack. The brown water stains on the ceiling. She coughed into her hand. Blood speckled her palm. She could hear Buddy moving around.

She looked up at him again. “Buddy, I already —”

Without warning, he wrenched her up by the arm. Callie’s legs struggled to stand. His elbow had smacked her harder than she’d first thought. The world had started to stutter, a record needle caught in the same rut. Callie coughed again, stumbling forward. Her entire face felt smashed open. A thick stream of blood ran down the back of her throat. The room was swirling like a globe. Was this a concussion? It felt like a concussion.

“Buddy, I think I —”

“Shut it.” His hand clamped down hard on the back of her neck. He muscled her through the living room and into the kitchen like a misbehaving dog. Callie was too startled to fight back. His fury had always been like a flash fire, sudden and all-encompassing. Usually, she knew where it was coming from.

“Buddy, I —”

He threw her against the table. “Will you fucking shut up and listen to me?”

Callie reached back to steady herself. The entire kitchen turned sideways. She was going to throw up. She needed to get to the sink.

Buddy banged his fist on the counter. “Stop playing around, dammit!”

Callie’s hands covered her ears. His face was scarlet. He was so angry. Why was he so angry?

“I’m dead fucking serious.” Buddy’s tone had softened, but the register had a deep, ominous growl. “You need to listen to me.”

“Okay, okay. Just give me a minute.” Callie’s legs were still shaky. She lurched toward the sink. Twisted on the faucet. Waited for the water to run clear. She stuck her head under the cold stream. Her nose burned. She winced, and the pain shot straight through her face.

Buddy’s hand wrapped around the edge of the sink. He was waiting.

Callie lifted her head. The dizziness nearly sent her reeling again. She found a towel in the drawer. The rough material scratched her cheeks. She stuck it under her nose, tried to staunch the bleeding. “What is it?”

He was bouncing on the balls of his feet. “You can’t tell anybody about the camera, okay?”

The towel had already soaked through. The blood would not stop pouring from her nose, into her mouth, down her throat. Callie had never wanted so desperately to lie down in bed and close her eyes. Buddy used to know when she needed that. He used to sweep her up in his arms and carry her down the hall and tuck her into bed and stroke her hair until she fell asleep.

“Callie, promise me. Look me in the eye and promise you won’t tell.”

Buddy’s hand was on her shoulder again, but more gently this time. The rage inside of him had started to burn itself out. He lifted her chin with his thick fingers. She felt like a Barbie he was trying to pose.

“Shit, baby. Look at your nose. Are you okay?” He grabbed a fresh towel. “I’m sorry, all right? Jesus, your beautiful little face. Are you okay?”

Callie turned back to the sink. She spat blood into the drain. Her nose felt like it was cranked between two gears. This had to be a concussion. She saw two of everything. Two globs of blood. Two faucets. Two drying racks on the counter.

“Look.” His hands gripped her arms, spinning her around and pinning her against the cabinets. “You’re gonna be okay, all right? I’ll make sure of that. But you can’t tell nobody about the camera, okay?”

“Okay,” she said, because it was always easier to agree with him.

“I’m serious, doll. Look me in the eye and promise me.” She couldn’t tell if he was worried or angry until he shook her like a rag doll. “Look at me.”

Callie could only offer him a slow blink. There was a cloud between her and everything else. “I know it was an accident.”

“Not your nose. I’m talking about the camera.” He licked his lips, his tongue darting out like a lizard’s. “You can’t make a stink about the camera, dolly. I could go to prison.”

“Prison?” The word came from nowhere, had no meaning. He might as well have said unicorn. “Why would —”

“Baby doll, please. Don’t be stupid.”

She blinked, and, like a lens twisting into focus, she could see him clearly now.

Buddy wasn’t concerned or angry or eaten up with guilt. He was terrified.

Of what?

Callie had known about the camera for months, but she had never let herself figure out the purpose. She thought about his weekend parties. The cooler overflowing with beer. The air filled with smoke. The TV blaring. Drunken men chuckling and slapping each other on the back as Callie tried to get Trevor ready so they could go to a movie or the park or anything that got them both out of the house.

“I gotta —” She blew her nose into the towel. Strings of blood spiderwebbed across the white. Her mind was clearing but she could still hear ringing in her ears. He had accidentally knocked the shit out of her. Why had he been so careless?

“Look.” His fingers dug into her arms. “Listen to me, doll.”

“Stop telling me to listen. I am listening. I’m hearing every damn thing you say.” She coughed so hard that she had to bend over to clear it. She wiped her mouth. She looked up at him. “Are you recording your friends? Is that what the camera is for?”

“Forget the camera.” Buddy reeked of paranoia. “You got conked in the head, doll. You don’t know what you’re talking about.”

What was she missing?

He said he was a contractor, but he didn’t have an office. He drove around all day working out of his Corvette. She knew he was a sports bookie. He was also an enforcer, muscle for hire. He always had a lot of cash on him. He always knew a guy who knew a guy. Was he recording his friends asking for favors? Were they paying him to break some knees, burn down some buildings, find some leverage that would close a deal or punish an enemy? Callie tried to hold on to the pieces of a puzzle she couldn’t quite snap together in her head. “What’re you doing, Buddy? Are you blackmailing them?”

Buddy held his tongue between his teeth. He paused a beat too long before saying, “Yeah. That’s exactly what I do, baby. I blackmail them. That’s where the cash comes from. You can’t let on that you know. Blackmail’s a big crime. I could be sent away for the rest of my life.”

She stared into the living room, imagined it filled with his friends — the same friends every time. Some of them Callie didn’t know, but others were a part of her life and she felt guilty that she was a partial beneficiary of Buddy’s illegal scheming. Dr. Patterson, the school principal. Coach Holt from the Bellwood Eagles. Mr. Humphrey, who sold used cars. Mr. Ganza, who manned the deli counter at the supermarket. Mr. Emmett, who worked at her dentist’s office.

What had they done that was so bad? What horrible things had a coach, a car salesman, a handsy geriatric asshole for the love of Christ, done that they were stupid enough to confess to Buddy Waleski?

And why did these idiots keep coming back every weekend for football, for basketball, for baseball, for soccer, when Buddy was blackmailing them?

Why were they smoking his cigars? Swilling his beer? Burning holes in his furniture? Screaming at his TV?

Let’s finish on the couch.

Callie’s eyes followed the triangle from the one-inch hole drilled into the front of the bar, to the couch directly across from it, to the giant TV that weighed more than she did.

There was a glass shelf underneath the set. Cable box. Cable splitter. VCR.

She had grown used to seeing the three-pronged RCA cable that hung down from the jacks on the front of the VCR. Red for the right audio channel. White for the left audio. Yellow for video. The cable threaded into one long wire that lay coiled on the carpet below the television. Not once, ever, had Callie wondered what the other end of that cable plugged into.

Let’s finish on the couch.

“Baby girl.” Buddy’s desperation was sweating out of his body. “Maybe you should go home, all right? Lemme give you some money. I told you I got paid for that job tomorrow. Good to spread it around, right?”

Callie was looking at him now. She was really looking at him.

Buddy reached into his pocket and pulled out a wad of cash. He counted off the bills like he was counting off all the ways he controlled her. “Buy yourself a new shirt, all right? Get some matching pants and shoes or whatever. Maybe a necklace? You like that necklace I gave you, right? Get another one. Or four. Be like Mr. T.”

“Do you film us?” The question was out before she could consider the kind of hell that the answer could rain down. They never made love in the bed anymore. It was always on the couch. And all those times he’d carried her back to tuck her in? It was right after they had finished on the couch. “Is that what you do, Buddy? You film yourself fucking me and you show it to your friends?”

“Don’t be stupid.” His tone was the same as Trevor’s when he promised he wasn’t tapping the glass on the aquarium. “I wouldn’t do that, would I? I love you.”

“You’re a goddam pervert.”

“Watch your nasty mouth.” He wasn’t screwing around with his warning. She could see exactly what was going on now — what had been going on for at least six months.

Dr. Patterson waving at her from the bleachers during pep rallies.

Coach Holt winking at her from the sidelines during football games.

Mr. Ganza smiling at Callie as he passed her mother some sliced cheese over the deli counter.

“You —” Callie’s throat clenched. They had all seen her with her clothes off. The things she had done to Buddy on the couch. The things that Buddy had done to her. “I can’t —”

“Callie, calm down. You’re getting hysterical.”

“I am fucking hysterical!” she screamed. “They’ve seen me, Buddy. They’ve watched me. They all know what I — what we —”

“Doll, come on.”

She dropped her head into her hands, humiliated.

Dr. Patterson. Coach Holt. Mr. Ganza. They weren’t mentors or fatherly figures or sweet old men. They were perverts who got off on watching Callie get screwed.

“Come on, baby,” Buddy said. “You’re blowing this out of proportion.”

Tears streamed down her face. She could barely speak. She had loved him. She had done everything for him. “How could you do this to me?”

“Do what?” Buddy sounded flip. His eyes darted down to the wad of cash. “You got what you wanted.”

She shook her head. She had never wanted this. She had wanted to feel safe. To feel protected. To have someone interested in her life, her thoughts, her dreams.

“Come on, baby girl. You got your uniforms paid for, and your cheerleading camp, and your —”

“I’ll tell my mother,” she threatened. “I’ll tell her exactly what you did.”

“You think she gives a shit?” His laugh was genuine, because they both knew it was true. “As long as the cash keeps coming, your mama don’t care.”

Callie swallowed the glass that had filled her throat. “What about Linda?”

His mouth fished open like a trout’s.

“What’s your wife gonna think about you fucking her son’s fourteen-year-old babysitter for the last two years?”

She heard the hiss of air sucking past his teeth.

In all of the time Callie had been with him, Buddy had talked constantly about Callie’s small hands, her tiny waist, her little mouth, but he had never, ever talked about the fact that there was more than thirty years between them.

That he was a criminal.

“Linda’s still at the hospital, right?” Callie walked over to the phone hanging by the side door. Her fingers traced the emergency numbers that were taped onto the wall. Even as she went through the motions, Callie wondered if she could go through with the call. Linda was always so kind. The news would devastate her. There was no way Buddy would let it get that far.

Still, Callie picked up the receiver, expecting him to wail and plead and beg for her forgiveness and reaffirm his love and devotion.

He did none of this. His mouth kept trouting. He stood like a frozen gorilla, his arms bulging out at his sides.

Callie turned her back to him. She rested the receiver against her shoulder. Stretched the springy cord out of her way. Touched the number eight on the keypad.

The entire world slowed down before her brain could register what was happening.

The punch to her kidney was like a speeding car sideswiping her from behind. The phone slipped from her shoulder. Callie’s arms flew up. Her feet left the ground. She felt a breeze on her skin as she launched into the air.

Her chest slammed into the wall. Her nose crushed flat. Her teeth dug into the Sheetrock.

“Stupid bitch.” Buddy palmed the back of her head and banged her face into the wall again. Then again. He reared back a third time.

Callie forced her knees to bend. She felt her hair rip from her scalp as she folded her body into a ball on the floor. She had been beaten before. She knew how to take a hit. But that was with someone whose size and strength were relatively close to her own. Someone who didn’t thrash people for a living. Someone who had never killed before.

“You gonna fuckin’ threaten me!” Buddy’s foot swung into her stomach like a wrecking ball.

Callie’s body lifted off the floor. She huffed all of the air out of her lungs. A sharp stabbing pain told her that one of her ribs had fractured.

Buddy was on his knees. She looked up at him. His eyes were crazed. Spit speckled the corners of his mouth. He wrapped one hand around her neck. Callie tried to scramble away but ended up on her back. He straddled her. The weight of him was unbearable. His grip tightened. Her windpipe flexed into her spine. He was pinching off her air. She swung at him, trying to aim her fist between his legs. Once. Twice. A sideswipe was enough to loosen his grip. She rolled out from under him, tried to find a way to stand, to run, to flee.

The air cracked with a sound she couldn’t quite name.

Fire burned across Callie’s back. She felt her skin being flayed. He was using the telephone cord to whip her. Blood bubbled up like acid across her spine. She raised her hand and watched the skin on her arm snake open as the phone cord wrapped around her wrist.

Instinctively, she jerked back her arm. The cord slipped from his grasp. She saw the surprise in his face and scrambled to get her back against the wall. She lashed out at him, punching, kicking, recklessly swinging the cord, screaming, “Fuck you, motherfucker! I’ll fucking kill you!”

Her voice echoed in the kitchen.

Suddenly, somehow, everything had come to a standstill.

Callie had at some point managed to spring to her feet. Her hand was raised behind her head, waiting to whip the cord around. Both of them stood their ground, no more than spitting distance between them.

Buddy’s startled laugh turned into an appreciative chuckle. “Damn, girl.”

She had opened a gash along his cheek. He wiped the blood onto his fingers. He put his fingers in his mouth. He made a loud sucking noise.

Callie felt her stomach twist into a tight knot.

She knew the taste of violence brought out a darkness in him. “Come on, tiger.” He raised his fists like a boxer ready for a knock-out round. “Come at me again.”

“Buddy, please.” Callie silently willed her muscles to stay primed, her joints to keep loose, to be ready to fight back as hard as they could because the only reason he was acting calm right now was because he had made up his mind that he was going to enjoy killing her. “It doesn’t have to be like this.”

“Sugar doll, it was always going to be like this.”

She let that knowledge settle into her brain. Callie knew that he was right. She had been such a fool. “I won’t say anything. I promise.”

“It’s too far gone, dolly. I think you know that.” His fists still hung loose in front of his face. He waved her forward. “Come on, baby girl. Don’t go down without a fight.”

He had nearly two feet and at least one hundred fifty pounds on her. The heft of an entire second human being existed inside of his hulking body.

Scratch him? Bite him? Pull out his hair? Die with his blood in her mouth?

“Whatcha gonna do, little bit?” He kept his fists at the ready. “I’m giving you a chance here. You gonna come at me or are you gonna fold?”

The hallway?

She couldn’t risk leading him to Trevor.

The front door?

Too far away.

The kitchen door?

Callie could see the gold doorknob out of the corner of her eye.

Gleaming. Waiting. Unlocked.

She walked herself through the motions — turn, left-foot-right-foot, grab the knob, twist, run through the carport, out into the street, scream her head off the whole way.

Who was she kidding?

All she had to do was turn and Buddy would be on her. He wasn’t fast, but he didn’t need to be. In one long stride, his hand would be around her neck again.

Callie stared all of her hatred into him. He shrugged, because it didn’t matter.

“Why did you do it?” she asked. “Why did you show them our private stuff?”

“Money.” He sounded disappointed that she was so stupid. “Why the hell else?”

Callie couldn’t let herself think about all those grown men watching her do stuff she did not want to do with a man who had promised he would always, no matter what, protect her.

“Bring it.” Buddy punched a lazy right hook into the air, then a slow-motion uppercut. “Come on, Rocky. Gimme whatcha got.”

She let her gaze ping-pong around the kitchen.

Fridge. Oven. Cabinets. Drawers. Cookie plate. NyQuil. Drying rack.

Buddy smirked. “You gonna hit me with a frying pan, Daffy Duck?”

Callie sprinted straight toward him, full out, like a bullet exploding from the muzzle of a gun. Buddy’s hands were up near his face. She tucked her body down low so that when he finally managed to drop his fists, she was already out of his reach.

She crashed into the kitchen sink. Grabbed the knife out of the drying rack.

Spun around with the blade slicing out in front of her. Buddy grinned at the steak knife, which looked like something Linda had bought at the grocery store in a six-piece set made in Taiwan. Cracked wooden handle. Serrated blade so thin that it bent three different ways before straightening out at the end. Callie had used it to cut Trevor’s hot dog into pieces because otherwise he would try to shove the whole thing in his mouth and start to choke.

Callie could see she’d missed some ketchup.

A thin streak of red ran along the serrated teeth. “Oh.” Buddy sounded surprised. “Oh, Jesus.” They both looked down at the same time.

The knife had slashed open the leg of his pants. Left upper thigh, a few inches down from his crotch.

She watched the khaki material slowly turn crimson.

Callie had been involved in competitive gymnastics from the age of five. She had an intimate understanding of all the ways that you could hurt yourself. An awkward twist could tear the ligaments in your back. A sloppy dismount could wreck the tendons in your knee. A piece of metal — even a cheap piece of metal — that cut across your inner thigh could open your femoral artery, the major pipeline that supplied blood to the lower part of your body.

“Cal.” Buddy’s hand clamped down on his leg. Blood seeped through his clenched fingers. “Get a — Christ, Callie. Get a towel or —”

He started to fall, broad shoulders banging into the cabinets, head cracking off the edge of the countertop. The room shook from his weight as he dropped down.

“Cal?” Buddy’s throat worked. Sweat dripped down his face. “Callie?”

Her body was still tensed. Her hand was still gripping the knife. She felt enveloped by a cold darkness, like she’d somehow stepped back into her own shadow.

“Callie. Baby, you gotta —” His lips had lost their color. His teeth began to chatter as if her coldness was seeping into him, too. “C-call an ambulance, baby. Call an —”

Callie slowly turned her head. She looked at the phone on the wall. The receiver was off the hook. Slivers of multi-colored wires stuck out where Buddy had ripped away the springy cord. She found the other end, following it like a clue, and located the receiver underneath the kitchen table.

“Callie, leave that — leave that there, honey. I need you to —” She got down on her knees. Reached under the table. Picked up the receiver. Placed it to her ear. She was still holding the knife. Why was she still holding the knife?

“That one’s b-broken,” Buddy told her. “Go to the bedroom, baby. C-call an ambulance.”

She pressed the plastic tight to her ear. From memory, she summoned a phantom noise, the bleating siren sound that a phone made when it was off the hook too long.

Wah-wah-wah-wah-wah-wah-wah... “The bedroom, baby. G-go to the —” Wah-wah-wah-wah-wah-wah-wah... “Callie.”

That’s what she’d hear if she picked up the phone in the bedroom. The unrelenting bleating and, looped over that, the operator’s mechanical voice —

If you’d like to make a call...

“Callie, baby, I wasn’t going to hurt you. I would never h-hurt —”

Please hang up and try again.

“Baby, please, I need —”

If this is an emergency...

“I need your help, baby. P-please go down the hall and —”

Hang up and dial 9-1-1.

“Callie?”

She laid the knife on the floor. She sat back on her heels. Her knee didn’t throb. Her back didn’t ache. The skin around her neck didn’t pulse where he had choked her. Her rib didn’t stab from his kicks.

If you’d like to make a call...

“You fucking bitch,” Buddy rasped. “You f-fucking, heartless bitch.”

Please hang up and try again.

Spring 2021

Sunday

1

Leigh Collier bit her lip as a seventh-grade girl belted out “Ya Got Trouble” to a captive audience. A gaggle of tweens skipped across the stage as Professor Hill warned the townsfolk about out-of-town jaspers luring their sons into horse-race gambling.

Not a wholesome trottin’ race, no! But a race where they set right down on the horse!

She doubted a generation that had grown up with WAP, murder hornets, Covid, cataclysmic social unrest, and being forcibly homeschooled by a bunch of depressed day drinkers really understood the threat of pool halls, but Leigh had to hand it to the drama teacher for putting on a gender-neutral production of The Music Man, one of the least offensive and most tedious musicals ever staged by a middle school.

Leigh’s daughter had just turned sixteen years old. She’d thought her days of watching nose-pickers, mamas’ boys, and stage hogs break into song were blissfully over, but then Maddy had taken an interest in teaching choreography so here they were, trapped in this hellhole of trouble with a capital T and that rhymes with P and that stands for pool.

She looked for Walter. He was two rows down, closer to the aisle. His head was tilted at a weird angle, sort of looking at the stage, sort of looking at the back of the empty seat in front of him. Leigh didn’t have to see what was in his hands to know that he was playing fantasy football on his phone.

She slipped her phone out of her purse and texted — Maddy is going to ask you questions about the performance.

Walter kept his head down, but she could tell from the ellipses that he was responding — I can do two things at once.

Leigh typed — If that was true, we would still be together.

He turned to find her. The crinkles at the corners of his eyes told her he was grinning behind his mask.

Leigh felt an unwelcome lurch in her heart. Their marriage had ended when Maddy was twelve, but during last year’s lockdown, they had all ended up living at Walter’s house and then Leigh had ended up in his bed and then she’d realized why it hadn’t worked out in the first place. Walter was an amazing father, but Leigh had finally accepted that she was the bad type of woman who couldn’t stay with a good man.

On stage, the set had changed. A spotlight swung onto a Dutch exchange student filling the role of Marian Paroo. He was telling his mother that a man with a suitcase had followed him home, a scenario that today would’ve ended in a SWAT standoff.

Leigh let her gaze wander around the audience. Tonight was the closing night after five consecutive Sunday performances. This was the only way to make sure all the parents got to see their kids whether they wanted to or not. The auditorium was one-quarter full, taped-off empty seats keeping everyone at a distance. Masks were mandatory. Hand sanitizer flowed like peach schnapps at a prom. Nobody wanted another Night of the Long Nasal Swabs.

Walter had his fantasy football. Leigh had her fantasy apocalypse fight club. She gave herself ten slots to fill out her team. Obviously, Janey Pringle was her first choice. The woman had sold enough toilet paper, Clorox wipes, and hand sanitizer on the black market to buy her son a brand new MacBook Pro. Gillian Nolan knew how to make schedules. Lisa Regan was frighteningly outdoorsy, so she could do things like build fires. Denene Millner had punched a pit bull in the face when it charged her kid. Ronnie Copeland always had tampons in her purse. Ginger Vishnoo had made the AP physics teacher cry. Tommi Adams would blow anything with a pulse.

Leigh’s eyes slid to the right, locating the broad, muscular shoulders of Darryl Washington. He’d quit his job to take care of the kids while his wife worked a high-paying corporate gig. Which was sweet but Leigh wasn’t going to survive the apocalypse only to end up fucking a meatier version of Walter.

The men were the problem with this game. You could have one guy, possibly two on your team, but three or more and all the women would probably end up chained to beds in an underground bunker.

The house lights came up. The blue and gold curtains swished closed. Leigh wasn’t sure whether she had dozed off or gone into a fugue state, but she was extraordinarily happy that the intermission had finally arrived.

No one stood up at first. There was some uncomfortable shifting in seats as people debated whether or not to go to the restroom. This wasn’t like the old days when everybody busted down the doors, eager to gossip in the lobby while they ate cupcakes and drank punch in tiny paper cups. There had been a sign at the entrance instructing them to pick up a plastic bag before entering the auditorium. Inside each was a playbill, a small bottle of water, a paper mask, and a note reminding everyone to wash their hands and follow the CDC guidelines. The rogue — or, as the school called them, non-compliant — parents were given a Zoom password so they could watch the performance in the maskless comfort of their own living rooms.

Leigh took out her phone. She dashed off a quick text to Maddy — The dancing was amazing! How cute was that little librarian? I’m so proud of you!

Maddy buzzed back immediately — Mom I am working

No punctuation. No emojis or stickers. But for social media, Leigh would have no idea that her daughter was still capable of smiling.

This was what a thousand cuts felt like.

She looked for Walter again. His seat was empty. She spotted him near the exit doors, talking to another broad-shouldered father. The man’s back was to Leigh, but she could tell by the way Walter was waving his arms that they were discussing football.

Leigh let her gaze travel around the room. Most of the parents were either too young and healthy to jump ahead in the vaccine line, or smart and wealthy enough to know they should lie about buying early access. They were all standing in mismatched pairs talking in low murmurs across the required distance. After a nasty brawl had broken out during last year’s Non-Denominational Holiday Celebration That Happened Around Christmas, no one talked about politics. Instead, Leigh caught snippets of more sports talk, the mourning of past bake sales, who was in whose bubble, whose parents were Covidiots or maskholes, and how men who wore their masks below their noses were the same jerks who acted like wearing a condom was a human rights violation.

She turned her focus toward the closed stage curtains, straining her ears to pick up the scraping and pounding and furious whispers as the kids changed out the set. Leigh felt the familiar lurch in her heart — not for Walter this time, but because she ached for her daughter. She wanted to come home to a mess in the kitchen. To yell about homework and screen time. To reach into her closet for a dress that had been “borrowed” or search for a pair of shoes that had been carelessly kicked under the bed. She wanted to hold her squirming, protesting daughter. To lie on the couch and watch a silly movie together. To catch Maddy giggling over something funny on her phone. To endure the withering glare when she asked her what was so funny.

All they did lately was argue, mostly via text in the morning and on the phone at six sharp every night. If Leigh had an ounce of intelligence she would back off, but backing off felt too much like letting go. She couldn’t stand not knowing if Maddy had a boyfriend or a girlfriend or had left a string of broken hearts in her wake or had decided to give up love for the pursuit of art and mindfulness. The only thing Leigh knew for sure was that every nasty fucking thing she had ever done or said to her own mother kept slamming into her like a never-ending tidal wave.

Except Leigh’s mother deserved it.

She reminded herself that their distance kept Maddy safe. Leigh stayed in the downtown condo they used to share. Maddy had moved to the suburbs with Walter. This was a decision they had all reached together.

Walter was legal counsel for the Atlanta Fire Fighters’ Union, so his job entailed Microsoft Teams and phone calls made from the safety of his home office. Leigh was a defense attorney. Some of her work was online, but she still had to go into the office and meet with clients. She still had to enter the courthouse and sit through jury selection and conduct trials. Leigh had already caught the virus during the first wave last year. For nine agonizing days, she’d felt like a mule was kicking her in the chest. As far as anyone knew, the risk for kids seemed to be minimal — the school touted its under-one-percent infection rate on its website — but there was no way she was going to be responsible for bringing the plague home to her daughter.

“Leigh Collier, is that you?”

Ruby Heyer pulled her mask down below her nose, then yanked it quickly back up, like it was safe if you did it fast.

“Ruby. Hi.” Leigh was grateful for the six feet between them. Ruby was a mom-friend, a necessary companion back when their kids were toddlers and it was either set up a play date or blow out your brains on the coffee table. “How’s Keely?”

“She’s fine, but long time, huh?” Ruby’s red-rimmed glasses bumped up on her smiling cheeks. She was a horrible poker player. “Funny seeing Maddy enrolled here. Didn’t you say you wanted your daughter to have an in-town education?”

Leigh felt her mask suck to her mouth as she went from mild annoyance to full-on burn-the-motherfucker-down.

“Hey, ladies. Aren’t the kids doing a terrific job?” Walter was standing in the aisle, hands tucked into his pants pockets. “Ruby, nice to see you.”

Ruby straddled her broomstick as she prepared to fly away. “Always a pleasure, Walter.”

Leigh caught the insinuation that she wasn’t part of the pleasure, but Walter was shooting her his don’t be a bitch look. She shot back her go fuck yourself look.

Their entire marriage in two looks. Walter said, “I’m glad we never had that three-way with her.” Leigh laughed. If only Walter had suggested a three-way. “This

would be a great school if it was an orphanage.”

“Is it necessary to poke every bear with a sharp stick?”

She shook her head, looking up at the gold leaf ceiling and professional sound and lighting rigs. “It’s like a Broadway theater in here.”

“It is.”

“Maddy’s old school —”

“Had a cardboard box for a stage and Maglite for a spot and a Mr. Microphone for sound and Maddy thought it was the best thing ever.”

Leigh ran her hand along the blue velvet seatback in front of her. The Hollis Academy logo was stitched in gold thread along the top, probably courtesy of a wealthy parent with too much money and not enough taste. Both she and Walter had been godless, public school-supporting, bleeding heart liberals until the virus hit. Now they were scraping together every last cent they could find to send Maddy to an insufferably snooty private school where every other car was a BMW and every other kid was an entitled cocksucker.

The classes were smaller. The students rotated in pods of ten. Extra staff kept the classrooms sanitized. PPE was mandated. Everyone followed the protocols. There were hardly ever any rolling lockdowns in the suburbs. Most of the parents had the luxury of working from home.

“Sweetheart.” Walter’s patient tone was grating. “Every parent would send their kid here if they could.”

“Every parent shouldn’t have to.”

Her work phone buzzed in her purse. Leigh felt her shoulders tense up. One year ago, she had been an overworked, under-compensated self-employed defense attorney helping sex workers, drug addicts, and petty thieves navigate the legal system. Today, she was a cog in a giant corporate machine representing bankers and small business owners who committed the same crimes as her previous clients, but had the money to get away with it.

Walter said, “They can’t expect you to work on a Sunday night.”

Leigh snorted at his naiveté. She was competing against dozens of twenty-something-year-olds with so much student loan debt that they slept at the office. She dug around in her purse, saying, “I asked Liz not to bother me unless it was life or death.”

“Maybe some rich dude just murdered his wife.”

She gave him the go fuck yourself look before unlocking her phone. “Octavia Bacca just texted me.”

“Everything okay?”

“Yes, but...” She hadn’t heard from Octavia in weeks. They’d made casual plans to meet for a walk at the Botanical Garden, but Leigh had never heard back, so she’d assumed that Octavia had gotten busy.

Leigh could see the text she’d sent at the end of last month —

Are we still on to walk?

Octavia had texted her back just now — So shitty. Don’t hate me. Below the text, a link popped up to a news story. The photo showed a clean-cut guy in his early thirties who looked like every clean-cut guy in his early thirties.

ACCUSED RAPIST INVOKES RIGHT TO SPEEDY TRIAL.

Walter asked, “But?”

“I guess Octavia is tied up on this case.” Leigh scrolled through the story, pulling out the details. “Stranger assault, not date rape, which isn’t the norm. The client is up on some serious charges. He claims he’s innocent — ha, ha. He’s demanding a jury trial.”

“That’ll make the judge happy.”

“And the jury.” No one wanted to risk exposure to the virus in order to hear a rapist say he didn’t do it. And even in the likely event that he did do it, rape was a fairly easy charge to plead down. Most prosecutors were hesitant to take on the fight because the cases tended to involve people who knew each other, and those pre-existing relationships further muddled the issue of consent. As a defense attorney, you negotiated for unlawful restraint or a lesser charge that would keep your client off the sex offender registry and out of jail and then you went home and took the longest, hottest shower you could tolerate to blast off the stink.

Walter asked, “Did he get bail?”

“’Rona rules.” Given the coronavirus, judges were loath to hold over defendants pending trial. Instead, they mandated ankle monitors and dared them to break the rules. Prisons and jails were worse than nursing homes. Leigh should know. Her own exposure had come courtesy of Atlanta’s City Detention Center.

Walter asked, “Prosecutor didn’t offer a deal?”

“I’d be shocked if they didn’t, but it doesn’t matter if the client won’t take it. No wonder Octavia’s been offline.” She looked up from her phone. “Hey, if the rain holds off, do you think I can bribe Maddy into sitting with me on your back porch?”

“I’ve got umbrellas, sweetheart, but you know she’s got an afterparty with her pod.”

Tears welled into Leigh’s eyes. She hated being on the outside looking in. A year had passed and she still went into Maddy’s empty bedroom at least once a month to cry. “Was it this hard for you when she was living with me?”

“It’s a lot easier to delight a twelve-year-old than it is to compete for a sixteen-year-old’s attention.” His eyes crinkled again. “She loves you so much, sweetheart. You’re the best mother she could ever have.”

Now her tears started to fall. “You’re a good man, Walter.”

“To a fault.”

He wasn’t joking.

The lights flickered. Intermission was over. Leigh was about to sit down, but her phone buzzed again. “Work.”

“Lucky,” Walter whispered.

She sneaked up the aisle toward the exit. A few of the parents glared at her over their masks. Whether it was for the current disruption or for Leigh’s part in last year’s Christmas-adjacent nasty brawl, she had no idea. She ignored them, feigning interest in her phone. The caller ID flashed Bradley, which was odd, because usually when her assistant called, it scrolled Bradley, Canfield & Marks.

She stood in the middle of the ridiculously plush lobby, ignoring the gold sconces that had probably been plundered from an actual tomb. Walter claimed she had a chip on her shoulder about ostentatious displays of wealth, but Walter hadn’t lived out of his car his first year in law school because he couldn’t afford rent.

She answered the phone, “Liz?”

“No, Ms. Collier. This is Cole Bradley. I hope I’m not interrupting.”

She nearly swallowed her tongue. There were twenty floors and probably twice as many millions of dollars separating Leigh Collier and the man who had started the firm. She had only laid eyes on him once. Leigh was waiting her turn in the elevator lobby when Cole Bradley had used a key to summon the private car that went straight to the top floor. He looked like a taller, leaner version of Anthony Hopkins, if Anthony Hopkins had put a plastic surgeon on retainer shortly after graduating from the University of Georgia Law School.

“Ms. Collier?”

“Yes — I’m —” She tried to get her shit together. “I’m sorry. I’m at my daughter’s school play.”

He didn’t bother with small talk. “I’ve got a delicate matter that requires your immediate attention.”

She felt her mouth open. Leigh was not setting the world on fire at Bradley, Canfield & Marks. She was doing exactly enough to keep a roof over her head and her daughter in private school. Cole Bradley employed at least one hundred baby lawyers who would stab her in the face to get this phone call.

“Ms. Collier?”

“I’m sorry,” Leigh said. “I’m just — honestly, Mr. Bradley, I’ll do whatever you want but I’m not sure I’m the right person.”

“Frankly, Ms. Collier, I had no idea you even existed until this evening, but the client asked for you specifically. He’s waiting in my office as we speak.”

Now she was really confused. Leigh’s highest-profile client was the owner of a pet supply warehouse who’d been charged with breaking into his ex-wife’s house and urinating in her underwear drawer. The case had been joked about in one of Atlanta’s alternative papers, but she doubted Cole Bradley read Atlanta INtown. “His name is Andrew Tenant,” Bradley said. “I trust you’ve heard of him.”

“Yes, sir. I have.” Leigh only knew the name because she’d just read it in the story Octavia Bacca had texted her.

So shitty. Don’t hate me.

Octavia lived with her elderly parents and a husband with severe asthma. There were only two reasons Leigh could think of that her friend would refer out a case. She was either skipping out on a jury trial because of the virus risk or she was creeped out by her presumed rapist client. Not that Octavia’s motivations mattered right now, because Leigh didn’t have a choice.

She told Bradley, “I’ll be there in half an hour.”

***

Most passengers flying into Atlanta airport looked out the window and assumed that Buckhead was downtown, but the cluster of skyscrapers at the uptown end of Peachtree Street had not been built for convention-goers, government services or staid, financial institutions. The floors were filled with high-dollar litigators, day traders, and private money managers who catered to the surrounding client base living in one of the wealthiest ZIP codes in the southeast.

The headquarters for Bradley, Canfield & Marks loomed over the Buckhead commercial district, a glass-fronted behemoth that crested at the top like a breaking wave. Leigh found herself in the belly of the beast, trudging up the parking deck stairs. The gate was closed for visitor parking. The first available space she could find was three stories underground. The concrete stairwell felt like murder territory, but the elevators were locked and she hadn’t been able to find a security guard. She took advantage of the time by going over in her head what Octavia Bacca had relayed over the phone during the drive over.

Or what she hadn’t been able to tell her.

Andrew Tenant had fired Octavia two days ago. No, he hadn’t given her an explanation why. Yes, Octavia had thought until that point that Andrew was satisfied with her counsel. No, she couldn’t guess why Tenant had made the change, but, two hours ago, Octavia had been instructed to transfer all of his case files to BC&M care of Leigh Collier. The so shitty text was meant as an apology for dumping a jury trial into her lap eight days before it was scheduled to begin. Leigh had no idea why a client would drop one of the best defense attorneys in the city when his life was on the line, but she had to assume the man was an idiot.

The bigger mystery to solve was how the hell Andrew Tenant even knew Leigh’s name. She had texted Walter, who was just as clueless, and that was the sum total of Leigh’s ability to mine information from her past because Walter was the only person currently in her life who had known her before she had graduated from law school.

Leigh stopped at the top of the stairs, sweat dripping down her back. She did a quick inventory of her appearance. She hadn’t exactly dressed up for her night at the theater. She had thrown her hair into an old-lady bun and chosen two-day-old jeans and a faded Aerosmith Bad Boys from Boston T-shirt, if only to stand in contrast to the Birkin-bagged bitches in the audience. She would have to swing by her office on the way to the top floor. Like everyone else, Leigh kept a courtroom outfit at work. Her make-up bag was in her desk drawer. The thought of having to put on her face for an accused rapist on a Sunday night that she should’ve been spending with her family ramped up her level of annoyance. She hated this building. She hated this job. She hated her life.

She loved her daughter.

Leigh looked for a mask in her purse, which Walter called her feedbag because she used it as a briefcase and, in the last year, a mini-pandemic supply store. Hand sanitizers. Clorox wipes. Masks. Nitrile gloves just in case. The firm tested them twice a week, and Leigh had already suffered through the virus, but, with the variants going around, it was better to be safe than sorry.

She checked the time as she looped the mask over her ears. She could steal a few seconds for her daughter. Leigh juggled her two phones, looking for the distinctive blue and gold Hollis Academy case on her personal device. The wallpaper photo was of Tim Tam, the family dog, because the chocolate Lab had shown Leigh a hell of a lot more love lately than her own daughter.

Leigh sighed at the screen. Maddy hadn’t texted back to Leigh’s profuse apology for her early departure. A quick perusal of Instagram showed her daughter dancing with friends at a small party in what looked like Keely Heyer’s basement, Tim Tam sleeping on a beanbag chair in the corner. So much for unquestioning devotion.

Leigh’s fingers slid across the screen, typing yet another text to Maddy — I’m sorry I had to leave, baby. I love you so much.

She stupidly waited for a response before opening the door. The overly air-conditioned lobby enveloped her in cold steel and marble. Leigh nodded to the security guard in his Plexiglas booth. Lorenzo was hunkered down over a cup of soup, shoulders up to his ears, bowl close to his mouth. Leigh was reminded of a succulent plant her mother used to keep in the kitchen window.

“Ms. Collier.”

Leigh silently panicked at the sight of Cole Bradley standing in the elevator lobby. Her hand flew up to the back of her hair. She could feel tendrils shooting out like a flattened octopus. The bad boys logo across her ratty T-shirt was an affront to his bespoke Italian suit.

“You caught me in the act.” He tucked a pack of cigarettes into his breast pocket. “I went outside for a smoke.”

Leigh felt her eyebrows rise up. Bradley practically owned the building. No one was going to stop him from doing anything.

He smiled. Or at least she thought he did. He was north of eighty years old but his skin was so tight that only the tips of his ears twitched.

He said, “Given the political climate, it’s good to be seen playing by the rules.”

The bell rang for the partners’ private elevator. The noise was so tinkly that it sounded like Lady Hoopskirts summoning the butler for afternoon tea.

Bradley retrieved a mask from his breast pocket. She assumed this, too, was for appearances. His age alone would’ve put him in the first group for the vaccine. Then again, the vaccine wouldn’t be a get-out-of-jail-free card until almost everyone was inoculated. “Ms. Collier?” Bradley was waiting at the open elevator doors.

Leigh hesitated, because she doubted underlings were allowed in the private car. “I was going to swing by my office to change into something more professional.”

“Unnecessary. They know the circumstances of the late hour.” He indicated that she should go in ahead of him.

Even with his permission, Leigh felt like a trespasser as she stepped into the fancy elevator. She pressed her calves against the narrow, red bench along the back wall. She had only glanced inside the private car once but, up close, she realized the black walls were paneled in ostrich skin. The floor was one giant slab of black marble. The ceiling and all of the floor buttons were trimmed in red and black because if you’d graduated from the University of Georgia, pretty much the biggest thing that had ever happened to you in your life was that you had graduated from the University of Georgia.

The mirrored doors slid closed. Bradley’s posture was ramrod straight. His mask was black with red piping. A pin on his lapel showed Uga, the Georgia Bulldog mascot. He touched the up button on the panel, sending them to the penthouse level.

Leigh stared straight ahead, still unsure of the etiquette. There were signs on the plebeian elevator warning people to keep their distance and avoid conversation. No such signs existed here, not even the inspection notice. Her nose tickled with the smell of Bradley’s aftershave mixed with cigarette smoke. Leigh hated men who smoked. She opened her mouth to breathe behind her mask. Bradley cleared his throat. “I wonder, Ms. Collier, how many of your fellow students at Lake Point High School ended up graduating with honors from Northwestern?”

He’d done his homework while she was breaking the sound barrier to get here. He knew she’d grown up on the bad side of town. He knew she’d ended up at a top-tier law school.

Leigh said, “UGA waitlisted me.”

She imagined he would’ve raised one of his eyebrows if the Botox would’ve let him. Cole Bradley wasn’t used to his subordinates having personalities.

He said, “You interned at a poverty law firm based out of Cabrini Green. After Northwestern, you returned to Atlanta and joined the Legal Aid Society. Five years later, you started your own practice specializing in criminal defense. You were doing quite well until the pandemic closed down the courts. The end of this month will mark your first-year anniversary with BC&M.”

She waited for a question.

“Your choices strike me as somewhat iconoclastic.” He paused, giving her ample opportunity to chime in. “I assume you had the luxury of scholarships, so finances didn’t dictate your career options.”

She kept waiting.

“And yet here you are at my firm.” Another pause. Another ignored opportunity. “Would it be impolite to note that you’re closer to forty than most of our first-year hires?”

She let her gaze find his. “It would be accurate.”

He openly studied her. “How do you know Andrew Tenant?”

“I don’t, and I have no idea how he knows me.”

Bradley took a deep breath before saying, “Andrew is the scion of Gregory Tenant, one of my very first clients. We met so long ago that Jesus Christ himself introduced us. He was waitlisted at UGA, too.”

“Jesus or Gregory?”

His ears twitched up slightly, which she understood was his way of smiling.

Bradley said, “Tenant Automotive Group started out with a single Ford dealership back in the seventies. You’ll be too young to remember the commercials, but they had a very memorable jingle. Gregory Tenant, Sr., was a fraternity brother of mine. When he died, Greg Jr. inherited the business and turned it into a network of thirty-eight dealerships across the southeast. Greg passed away from a particularly aggressive form of cancer last year. His sister took over the day-to-day operations. Andrew is her son.”

Leigh was still marveling at anyone using the word scion.

The elevator bell tinkled. The doors slid open. They had reached the top floor. She could feel cold air fighting against the umbrella of heat outside. The space was as cavernous as an aircraft hangar. The overhead fixtures were off. The only lights came from the lamps on the steel and glass desks standing sentry outside closed office doors.

Bradley walked to the middle of the room and stopped. “It never fails to take my breath away.”

Leigh knew he meant the view. They were in the trough of the giant wave at the top of the building. Massive pieces of glass reached at least forty feet to the crest. The floor was high enough above the light pollution for them to see tiny pinpoints of stars punching through the night sky. Far below, the cars traveling along Peachtree Street paved a red and white trail toward the glowing mass of downtown.

“It looks like a snow globe,” she said.

Bradley turned to face her. He had taken off his mask. “How do you feel about rape?”

“Definitely against it.”

His expression told Leigh that the time for her to have a personality was over.

She said, “I’ve handled dozens of assault cases over the years. The nature of the charge is irrelevant. The majority of my clients are factually guilty. The prosecutor has to prove those facts beyond a reasonable doubt. You pay me a hell of a lot of money to find that doubt.”

He nodded, approving of her response. “You’ve got jury selection on Thursday, with the trial commencing one week from tomorrow. No judge will grant you a continuance based on substituting counsel. I can offer you two full-time associates. Will the truncated timeline be a problem?”

“It’s a challenge,” Leigh said. “But not a problem.”

“Andrew was offered a reduced charge in exchange for one year of monitored probation.”

Leigh pulled down her mask. “No sex offender registry?”

“No. And the charges roll off if Andrew stays out of trouble for three years.”

Even this far into the game, Leigh was always surprised by how fantastic it was to be a white, wealthy man. “That’s a sweetheart deal. What are you not telling me?”

The skin around Bradley’s cheeks rippled in a wince. “The previous firm had a private investigator do some digging around. Apparently, a guilty admission on this particular reduced charge could lead to further exposure.”

Octavia hadn’t mentioned that detail. Maybe she hadn’t been updated before she was fired, or maybe she had seen the potential ratfuck and was glad to be out of it. If the PI was right, the prosecutor was trying to lure Andrew Tenant into pleading guilty to one rape so they could show a pattern of behavior that linked him to other assaults.

Leigh asked, “How much exposure?”

“Two, possibly three.”

Women, she thought. Two or three more women who had been raped.

“No DNA on any of the possible cases,” Bradley said. “I’ve gathered there’s some circumstantial evidence, but nothing insurmountable.”

“Alibi?”

“His fiancée, but —” Bradley shrugged it off the same as a jury would. “Thoughts?”

Leigh had two: either Tenant was a serial rapist or the district attorney was trying to get him to self-incriminate into being labeled one. Leigh had seen this kind of prosecutorial fuckery when she worked on her own, but Andrew Tenant wasn’t a busboy who copped a guilty plea because he didn’t have the money to fight it. She knew in her gut that Bradley was holding something else back. She chose her words carefully. “Andrew is the scion of a wealthy family. The district attorney knows you don’t take a shot at the king if you think you’ll miss.”

Bradley didn’t respond, but his demeanor became more guarded. Leigh heard Walter’s earlier question zinging around her head. Had she poked the wrong bear with the wrong stick? Cole Bradley had asked her how she felt about rape cases. He hadn’t asked her how she felt about innocent clients. By his own admission, he had known the Tenant family since he was in short pants. For all she knew, he could be Andrew Tenant’s godparent.

Bradley clearly wasn’t going to share his thinking. He extended his arm, indicating the last closed door on the right. “Andrew is in my conference room with his mother as well as his fiancée.” Leigh pulled up her mask as she walked past her boss. She recalibrated herself away from being Walter’s wife and Maddy’s mother and the plucky gal who’d joked with a human skeleton inside a private elevator. Andrew Tenant had asked for Leigh specifically, probably because she was still coasting on her pre-BC&M reputation, which fell somewhere between a hummingbird and a hyena. Leigh had to be that person now or she’d not only lose the client, but possibly her job.

Bradley reached ahead of her to open the door.

The downstairs conference rooms were smaller than a Holiday Inn toilet and operated on a first-come, first-serve basis. Leigh had been expecting a slightly larger version of the same, but Cole Bradley’s personal meeting space was more like a suite at the Waldorf, down to the fireplace and a wet bar. There was a heavy glass vase of flowers on a pedestal. Photographs of various Uga bulldogs across the years lined the back wall. A painting of Vince Dooley hung above the fireplace. Stacks of legal pads and pens were on the black marble credenza. Trophies for various legal prizes crowded out rows of water bottles. The conference table, which was approximately twelve feet long and six feet wide, was made from redwood. The chairs were black leather.

Three people sat at the far end of the table, faces uncovered. She recognized Andrew Tenant from his photo in the news story, though he was better looking in person. The woman clutching his right arm was late-twenties with a tattoo sleeve and an eat shit snarl that any mother would want for her son.