Life

Turmoil In The Government Is Nothing New

Over the past few weeks, the news cycle has been absolutely dominated by stories alleging that life in the West Wing is chaotic — especially this week, in the aftermath of national security adviser Michael Flynn's resignation, which the Washington Post called "a major crisis for the fledgling administration." The circumstances of Flynn's departure, among other issues, led Senator John McCain to call the Trump administration a place where “nobody knows who’s in charge and nobody knows who’s setting policy” and various publications to publish articles speculating on staff unrest.

This news may comfort you or terrify you, depending on your perspective and personal hopes for the next four years; however, as usual, history provides a dose of perspective — this isn't the most unexpected, most scandal-ridden, or even most bizarre government in history (though, hey, we're only a few weeks into the administration!).

Many historical situations that seem to parallel the Trump administration can be found in royal or papal courts, which clustered around a central figure, because that's often how governments have been organized throughout history. It's also one of the arrangements that's most prone to intrigue, back-stabbing, complete chaos, and so many plot twists historians get cross-eyed. (Hell, it's even been made into a board game.) If you have a huge swathe of people all trying to get the favor of one particular person and work their way up the hierarchy for their own advantage, you're basically inviting a free-for-all. And, as history shows us, free-for-alls rarely turn out well.

The Papal Courts Of The Borgias

The Borgias may not entirely deserve their historical reputations as bloodthirsty, depraved poisoners, but they did run courts that were riddled with intrigue and gross corruption. The main offender was the Pope Alexander VI, who bought his way to the papal throne and proceeded to wreak havoc while on it, appointing relatives left and right to various positions within the highest levels of the Catholic Church and shifting alliances with basically every state he dealt with. The court went into utter meltdown, though, when he started a program of "confiscation" in the 1490s in which he targeted the wealthy, had them arrested for treason and executed, then seized their lands and money. One historian wrote that "the pontificate of Alexander IV came to symbolize all that was morally evil and abandoned."

The Chaotic Purges Of Yeongsangun

If you want a case of court intrigue gone badly wrong, the reign of Yeongsangun of Korea's Joseon dynasty is a pretty good example. Korean imperial history is littered with stories of court back-stabbings and courtier machinations, but it came to a serious head when Yeongsangun came onto the throne and proceeded to battle intently with everybody else in his circle.

His motivations were pretty understandable, even if his reaction was not: along with all the other aggravations of running a gossipy court, he was informed by a courtier that his beloved mother, Queen Yun, had actually been secretly executed when he was only four. Yeongsangun reacted to this by going to war with the court. He fired and killed a huge swathe of officials, abolished entire departments, dug up the corpses of people he particularly didn't like and had them mutilated, and exiled courtiers left and right. In the end, the courtiers managed to wrestle back control, demoted him to prince, and sent him to die on a remote island.

The Bonkers Debauchery Of Charles II

Charles II of England has one of the most famous courts in history, for the good reason that it was one of the sexiest. Everybody in it had a mistress (or 15) and was intent on having a good time. The preoccupation with pleasure, though, didn't keep it from also being ridiculously corrupt and prone to extensive infighting; it just added an interesting extra dimension. According to one historian,

"the Court represented a monstrous spectacle of 'wanton talk' and obscene writing, drunken brawling, riot, injury, outrage, window-smashing and wife-snatching, a general state of warfare, both verbal and physical, in which sexuality and disease were the weapons."

And it was true that a lot of the court arguments were to do with women: in one famous episode, after being informed that the king's brother was having an affair with his wife, the Duke of Southesk apparently went to a prostitute, deliberately contracted venereal disease, and therefore transferred it to his rival.

Charles also narrowly avoided an assassination attempt as he left the horse races because his house caught on fire, forcing him to leave early — a plot that, when discovered, led to the execution of numerous high-ranking courtiers for treason. (There was rather a lot of attempted treason about at the time.)

The Two Competing Courts Of Heian Period Japan

Japan in the Heian Period was technically ruled by an emperor, but through years of machinations behind the scenes, a family named the Fujiwara had gradually obtained a stranglehold over the court (namely by marrying all their women to high-ranking members of royal and court families). They never really tried to take over the emperor's job itself; they just made their family regents to every successive child-emperor and so ran the joint for over a hundred years. (It was also an intensely complicated bureaucracy with huge numbers of aristocrats and countless ritual ceremonies.) Eventually, though, the imperial family wanted a bit of control back.

In 1086, after a few generations of emperors gradually attempting to reclaim control, the Emperor Shirakawa instituted the practice of "cloistered rule": he abdicated in favor of his young son, but in actual fact ran a parallel court from a monastery with its own private army. It was a hell of a way to try to cut the knees off the court factions — and it actually worked.

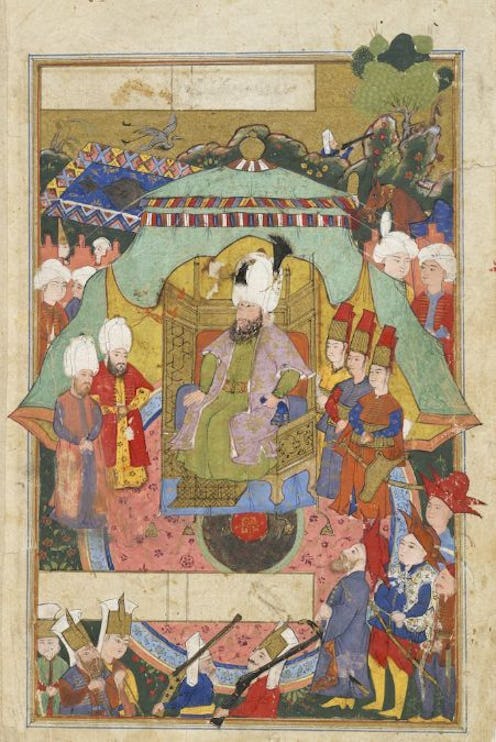

The Ritual Murders Of The Ottoman Empire

Imagine a situation in which court intrigue is so chaotic and time-consuming, the court's leaders felt that the only efficient alternative was ritual mass murder. That was the situation in the Ottoman Empire from the 15th to the 17th centuries. The problem was that Ottoman sultans traditionally had huge numbers of sons, thanks to their large harems — all of whom would descend into massive infighting, court alliance-making, and inevitable civil war whenever their father died. In order to simplify matters, the sultanate made a rule: if you managed to seize the throne, you had to murder all your brothers and male relatives immediately, to make sure none of them could depose you. No exceptions.

This didn't happen as regularly as you might think; the biggest swathe of murders happened when Mehemmed III took the throne in 1595 and proceeded to execute 19 competing other men. It didn't solve all the issues, though; the harems themselves continued to be hotbeds of infighting and problems (if you don't believe me, know that there was a show on Turkish TV devoted to the battle between concubines in the court of Suleyman the Magnificent which broke ratings records). Jostles for power and ensuing chaos: they're never pretty, but at least we know they're not new.