Books

The (Sort Of) True Story Of Dr. Jekyll & Mr. Hyde Is Straight Up Terrifying

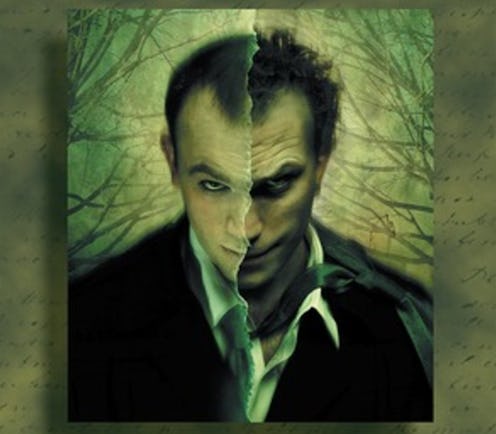

You already know the story of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde: a revered scientist and "reputable gentleman" called Dr. Jekyll drinks a potion and becomes the cruel, nefarious Mr. Hyde. It's a tale of horror that's been told and re-told. The characters frequently feature in gothic monster mash ups, like the graphic novel The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen, or the feminist re-telling The Strange Case of the Alchemist's Daughter, or the fever dream that is the TV show Once Upon a Time. Their names have become shorthand for being terrifyingly "two-faced."

But is The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde based on a true story?

The short answer is: kind of.

The long answer is that Scottish author Robert Louis Stevenson was sick in bed when he started writing Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. According to his stepson, he wrote the first draft in three frantic days, and then gave it to his wife, Fanny, to edit. Fanny pointed out that he'd written a fine story, but he'd completely missed the allegory. She wanted more social commentary. Robert took the feedback to heart, burned his manuscript, and completely re-wrote it in another three days, turning his horror story into an insightful critique of upper class male duplicity (thanks, Fanny).

Because there is no Hyde, you see. But there were two very real Jekylls.

The first "Jekyll" in Robert Louis Stevenson's life was reportedly the notorious Deacon Brodie. Brodie was a bourgeois, well-to-do craftsman in Edinburgh of the 1700's. He was from a respectable family, and held considerable political power as a City Councillor. He crafted cabinets and locks for Edinburgh's wealthiest residents.

And then, late at night, he used his locksmith skills to break into their homes and steal their money to support his gambling, cockfighting, and secret mistresses. He led a double life: respectable and wealthy cabinet designer by day, common thief by night.

Deacon Brodie's crime spree lasted from 1768-1788, when he was finally caught after trying to rob a government tax office. 40,000 people attended his hanging.

Brodie was executed long before Robert Louis Stevenson was born (although he did have a Brodie cabinet in his childhood bedroom), but a teenaged Stevenson was obsessed with Deacon Brodie. He attempted to write a play about the gentleman burglar, which he eventually re-wrote and produced just a few years before writing Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde.

The play wasn't exactly successful, but clearly the story stuck in Stevenson's mind. Especially after a second "Jekyll" showed up in his life, this one far closer to home:

Eugene Chantrelle was a French teacher, a failed doctor, and a friend of Robert Louis Stevenson. The two met up for drinks from time to time at the home of Stevenson's old French teacher. Stevenson liked being able to keep up his French and (presumably) hang out with his fancy friends. Chantrelle was, by all accounts, charming and intelligent and normal.

And then Eugene Chantrelle murdered his wife.

Over the course of Chantrelle's trial, evidence emerged that he had a long history of preying on teenage girls, sexually assaulting women, abusing his wife, and allegedly poisoning four or five other women as well. His wife, Lizzie, was 16 and pregnant when they got married. She had three young children by the time he took out a large life insurance policy against her death, and then poisoned her with a lethal dose of opium.

Stevenson was horrified. He was present for the trial, an experience which left him traumatized. This was not the fun, cabinet-making gentleman criminal of his youth — this was his friend, a "respectable" man who had been assaulting and murdering women for years.

Now here's where Fanny's notes come back into play: Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde is based on these true stories. But it's not that Stevenson thought these men were drinking mad scientist juice that caused them to lose all control. His point is that they weren't. There are, of course, many interpretations for Stevenson's story. There are also many flaws to it, like the shocking lack of female characters, the overtly racist visions of Hyde that have cropped up over the years, and the fact that shortness apparently equals deviousness.

But the crucial point that many interpretations of the story seems to miss is that Jekyll is already a bad dude. Jekyll is not the "good" to Hyde's "bad." It's just that Jekyll's desire to hurt people and engage in "lowly" vices is at odds with his reputation as a upstanding guy. He deliberately creates the disguise of Mr. Hyde so he can do the terrible things he already wanted to do, and face zero consequences to his actions.

Jekyll admits this when we finally get his side of the story:

"Men have before hired bravos to transact their crimes, while their own person and reputation sat under shelter. I was the first that ever did so for his pleasures. I was the first that could plod in the public eye with a load of genial respectability, and in a moment, like a schoolboy, strip off these lendings and spring headlong into the sea of liberty. But for me, in my impenetrable mantle, the safety was complete. Think of it—I did not even exist! Let me but escape into my laboratory door, give me but a second or two to mix and swallow the draught that I had always standing ready; and whatever he had done, Edward Hyde would pass away like the stain of breath upon a mirror; and there in his stead, quietly at home, trimming the midnight lamp in his study, a man who could afford to laugh at suspicion, would be Henry Jekyll."

The more he takes joy in his disguise of Mr. Hyde, though, the more monstrous his behavior becomes—it turns out, being held accountable was basically the only thing keeping wealthy, mild-mannered Dr. Jekyll from stealing and murdering and trampling little girls in the street.

But Jekyll can still sleep at night because it's Hyde doing these things, and *definitely* not him at all:

"The pleasures which I made haste to seek in my disguise were, as I have said, undignified; I would scarce use a harder term. But in the hands of Edward Hyde, they soon began to turn toward the monstrous. When I would come back from these excursions, I was often plunged into a kind of wonder at my vicarious depravity...Henry Jekyll stood at times aghast before the acts of Edward Hyde; but the situation was apart from ordinary laws, and insidiously relaxed the grasp of conscience. It was Hyde, after all, and Hyde alone, that was guilty. Jekyll was no worse; he woke again to his good qualities seemingly unimpaired; he would even make haste, where it was possible, to undo the evil done by Hyde. And thus his conscience slumbered."

It's Hyde doing bad things, not him. Never mind that he created Hyde for "pleasure," so that he could do bad things and not get caught.

It's only when Jekyll realizes that he's turning into Hyde at random, and that he's running out of supplies for his mad scientist juice, that he truly starts to panic. He's going to get stuck as Hyde. He's going to lose the comfortable, "innocent" guise of Dr. Jekyll to fall back on, the upper class gentleman who could never be responsible for Hyde's crimes. He's going to become Hyde permanently. If Hyde gets in trouble, he's going to face a consequence. And he'd rather die than do that.

Robert Louis Stevenson saw several theatrical productions of his story produced within his lifetime, and he was consistently annoyed by versions that interpreted Jekyll as a man with multiple personalities, or that depicted Hyde as a representation of sexual freedom. In a letter to the editor of the New York Sun, Stevenson insisted that Hyde is not meant to be a "mere voluptuary" (although, Stevenson adds that there's "no harm" in that).

In that same letter, Stevenson says that it is Jekyll's "selfishness and cowardice" that releases Hyde, and nothing else.

Jekyll isn't sick or sexually repressed. He's a hypocrite. He thinks privilege and potions can save him from taking responsibility for his violence. That's what Fanny and Robert understood. That's what must have made Robert feel sick when he thought back on drinking and laughing in a well-furnished parlor with the murderer Eugene Chantrelle. That's what drove him to sit up writing all night in his sick bed, burning the manuscripts that didn't live up to the story that he and Fanny wanted to tell.

So is Jekyll and Hyde based on a true story? Yes. A story that continues to be true, as long as all the "respectable" Jekylls out there refuse to take responsibility for Hyde.