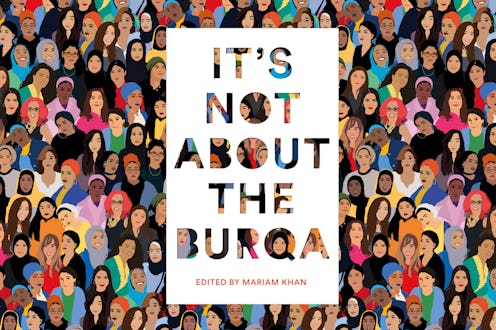

Books

Here's What You Need To Know About Being A British, Feminist, Muslim Woman In 2019

To many, being a Muslim woman and a feminist means existing as an oxymoron. The media disproportionately presents Muslim women as women who are married to ISIS soldiers, wear burqas, or are involved in honour killings. All of these conversations are important and should be discussed, but Muslim women are also scientists, world leaders, activist, politicians, and ordinary people. Yet we are rarely viewed this way.

By comparison, feminists in the West are viewed as women who fight period poverty, fight to #freethenipple, and fight for the right to not wear heels at work. I fight for for these things too, but that fight is not seen as mine, despite me being a woman who lives in the West. People find it difficult to see how these two identities — being a Muslim and a feminist — can co-exist, but they can.

Sometimes I think people are more willing to believe that they’re going to win the lottery, or that scientists will find life on another planet, before they meet a Muslim woman who also identifies as a feminist. As Muslim women, we are not only on our journey of faith, but on our journey of feminism. We don’t know how every single aspect of one identity will sit with the other, or how it won’t sit with it, and we are working through that. But that’s OK, because both are evolving and that’s a process we all go through as humans.

Muslim women exist as radicals both within their own communities and outside of them.

For me, Islam is a religion that empowers Muslim women. And my religion has never been the issue. In my opinion, Islam was, and is, more feminist than mainstream feminism (read: white feminism), which claims to be “for all women” but caters mainly to those who are white and middle class. I, as a Muslim woman, had basic rights like being able to work, to own property, to be educated, before many women in the West did.

In my journey to understanding why my feminism isn’t mainstream and why others can’t accept it, I have realised that the initial feminist movements in the West were unwilling to include anyone that didn’t fit the default of white and middle class. This was, and is, part of the wider colonial mindset that privileges white men, then white women, more than anyone in society by making their views the default for everyone else. Despite the “end” of colonisation, minds and outlooks have not been decolonised. The feminist default when it comes to women has been, and is, the actions of white, middle class women, and this means that women like me are actually oppressed and not liberated. If I’m not able to accept their bestowed liberation, or if my liberation or empowerment looks different to theirs, I’m doing it wrong.

When it comes to Muslim women and feminism, it seems Muslim women exist as radicals both within their own communities (for identifying as feminist due to lack of understanding of Muslim women’s right within our own communities) and outside of them (for daring to be a Muslim and a feminist). Still, we are the people with little to no structural power in the grand scheme of society, and largely perceived as people with no agency.

But this isn’t what my feminism is. I don’t believe that there should be a default group of women when it comes to feminism, because the intersection of our identities as woman of colour and faith often mean we navigate our lives differently to our white, middle class counterparts, who are unable or unwilling to see our struggles.

Feminism doesn’t belong to any one woman more than another.

In the last few years, my feminism has become a space for all those who identify as women, and I’m constantly challenging myself to make it more inclusive. I believe this has been the single biggest failure of feminism from its inception (again, read: white feminism, though it's important to note that a person needn't be white to embody or uphold the concept of “white feminism.”) Its refusal to evolve and include others has left those who advocate for all intersectional feminisms at a crossroads.

In my mind, I see a table where those who perpetuate white feminism sit, and I see myself sitting at a separate table where all other women are sitting. While I no longer ask for a space at their table, I will still call out those who advertise a space for all women but only advocate for certain women. I’m tired of feminism being co-opted. Feminism doesn’t belong to any one woman more than another.

This article was originally published on