Books

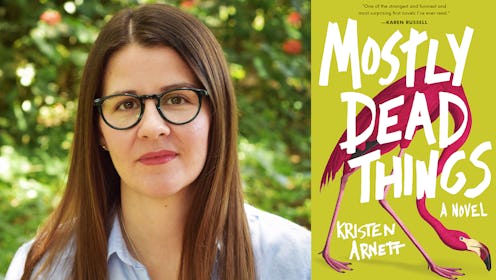

This Queer Summer Novel Is A Weird, Wonderful Ode To Central Florida

As a teenager, Kristen Arnett had a secret girlfriend. They never mentioned their relationship to anyone. But that was the '90s in Central Florida, and it wasn't the right time or place for Arnett to tell people about her relationship. "For me, it made sense to do that, because I couldn't really talk to anybody in my family or anybody about being queer," she says.

Setting is just as much about the beliefs and attitudes of the people who live there as it is about topography or description. It’s the people that make the place. So the setting of Arnett’s New York Times bestselling novel Mostly Dead Things isn’t the predictable Florida of postcards and headlines. Instead, it takes place in the Central Florida of Arnett's experience — a place that has not always been welcoming of her identity, and a place that is home. The novel follows Jessa-Lynn Morton, who takes over her family’s taxidermy business after her father dies by suicide. Jessa-Lynn's grief — over both the death of her father and the loss of her lesbian lover — sets the foundation for a story about how large a part our memories play in the construction of ourselves. Arnett’s memories, especially those of growing up as a closeted teen in Central Florida, inform the story’s sense of place.

I know how eager many people can be to leave. Unlike them, Arnett has never been in a hurry to go.

Born in 1980, Arnett is a third-generation Central Floridian. I grew up in Florida, and am a seventh-generation Floridian myself, so I know how eager many people can be to leave. Unlike them, Arnett has never been in a hurry to go. After graduating high school, she attended Rollins College in Winter Park, then earned her Master’s of Library Science at Florida State University. Now she is a librarian at Barry College of Law in Orlando, where she lives, writes, and hopes to create gay spaces that encourage a new generation to love who they are — something it has taken Arnett years to do.

In high school, Arnett was in denial about her queerness. She saw how difficult it would be just to live an openly gay life in such her closed-minded community. "I just felt really weird," says Arnett. "Like something was wrong with me all the time."

Arnett attributes this, at least partially, to the shortage of queer spaces in Orlando at the time. Even those that did exist, like Parliament House, a gay resort and nightlife spot, were so far outside Arnett’s world that there was no way she could have known about them. The effect was isolating — and surprising. "[Orlando] is very queer. You have Disney, and so many queer people work at Disney, but there’s just not a ton of queer spaces [here]… And one less now, since Pulse isn’t around anymore," she says, referring to the gay bar and club in Orlando which closed after 49 people were murdered in a mass shooting in 2016.

"The source of that kind of black humor,” Arnett says, “comes from how this is such a cyclical kind of place to live.”

That feeling of isolation was compounded by her family’s religiousness. Arnett remembers many conversations about homosexuality that took place in her church — all of them with the same lesson: "People like me were going to hell," Arnett says. "[Being gay] was very specifically terrible, like there’s not anything worse you can tell your family. They’d almost rather hear you’d murdered someone!" Arnett's family still lives in the Orlando area, but she isn’t on speaking terms with them, an experience that is all too common to queer life.

Arnett approaches my questions about her past with a dark sense of humor, something that is also present in her book. She perceives it to be such an essential part of Central Floridians’ attitude toward life. "The source of that kind of black humor,” Arnett says, "comes from how this is such a cyclical kind of place to live."

She says she first began to think of Florida this way after a friend brought up the state's association with death: It's a place where people retire, they said, and where people maybe come to die. Arnett had only ever perceived of Florida as the opposite: It's a place where everything is teeming with life. "Everything is growing, creeping,” she says. "It feels very juicy, like, just living all the time. Floridians are confronted daily with the reality of life’s finitude. It’s a place associated with death, for sure, but it’s also unavoidably, in-your-face full of life."

Maybe that’s why so many Floridians joke about hurricanes, even while they’re barreling down on us. We’re all so attuned to our own mortality that we can see the humor in serious situations.

“I wanted it to feel like what I experienced personally in summertime, or like those tactile sensations, the physical experience of being in Florida.”

If you follow her on Twitter, you are likely already familiar with that laughter-in-the-dark mentality, ever-present in her memes and posts about her life. You probably have also noticed that she spends a lot of time outside in the Florida sun, lounging or hanging out with her dogs.

"Mostly Dead Things is very heavily influenced by my experience being outside in Central Florida,” says Arnett, noting that there are very few books set in the area. "I wanted it to feel like what I experienced personally in summertime, or like those tactile sensations, the physical experience of being in Florida." To accomplish this, Arnett called on all of the senses to craft a world that felt, to me, like home.

Arnett also dug into the places that gave her a sense of belonging even while she was in the closet. Her book launch took place in one of those places: Park Avenue CDs, a strip mall punk-rock music store decorated with dozens of snow globes, a neon pentagram, and hammered tin accents in the shape of clouds. It was where she and her friends always hung out in high school.

"I never had any money," says Arnett. "I couldn’t afford to buy anything in there. But I was always in that store. It was such a part of growing up for me, looking at music and people watching in that store." To her, it's quintessentially Orlando. "I love places that have been here for a while, that you have memories associated with them. And I feel like they disappear sometimes," says Arnett. "Park Avenue CDs is one of those places I really want to stick around."

Arnett wanted to do a reading there because it was a locus for her memories. “Being able to do a reading with them,” says Arnett, “really spoke to me just as a person, especially because the book is so much about memory and nostalgia.”

“I’m a queer person. I live here. I’m going to make space. I’m going to make my own community.”

At the reading itself, Arnett told the audience she remembered being a closeted teenager there, and how it was one of the only places where she felt even the slightest sense of belonging. She says she wants to make sure young queer people of Central Florida feel more comfortable than she did. "That’s the thing I feel like I’m doing,” says Arnett. “I’m a queer person. I live here. I’m going to make space. I’m going to make my own community."