Life

People Are Tweeting #LetHerWork In Response To A Sportscaster Being Assaulted On Live TV

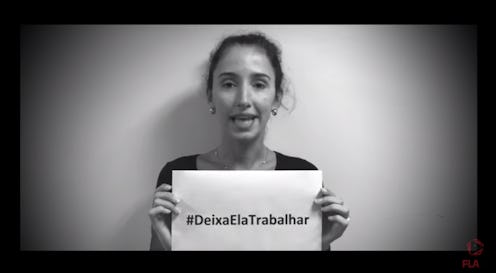

After a video of a Brazilian sports journalist being kissed on air without her permission went viral, a powerful movement for change has emerged from Brazil: Deixa Ela Trabalhar. Although many are becoming familiar with the movement through people tweeting under the hashtags #DeixaElaTrabalhar, or #LetHerWork in English, it’s more than just a social media convention; a coalition begun by 52 women reporters and journalists, it aims to call out and end the sexist treatment of women in sports journalism in Brazil. Their voices are loud, and they’re making sure the problem can no longer be ignored.

According to BuzzFeed News, the campaign saw its origins in a video clip football reporter Bruna Dealtry posted to her Facebook page on March 13 showing a man kissing her without her consent while she was in the middle of a broadcast. It left her “not knowing how to act and without understanding how one can feel in the right to do so,” Dealtry wrote (via Google Translate) in a post accompanying the video. She went on to discuss everything she had done to earn her career — “College, courses, many lost weekends, many soccer games analyzed, tactical study, technical, research, etc.” — and how much she loved her job. “But,” she wrote, “for the simple fact of being a woman in the midst of a crowd, none of this had value to him”; he saw her only as an object he wanted and felt entitled to have.

And that, she drove home, is not right. “I'm a soccer reporter, I'm a woman, and I deserve to be respected,” she said.

BuzzFeed News reports that around 50 Brazilian journalists chatting in a WhatsApp group message for International Women’s Day had seen the clip and realized how pervasive the issue is — and that something needed to be done about it. “We figured out that most of us had the same story,” Bibiana Bolson told BuzzFeed. “Every single day we have to handle the jokes, the comments, even the decisions that sometimes are not taking based on meritocracy, but with a little bit of sexism. It's important that we feel safe in stadiums, working with sports fans' support, and we want more legal support about it.”

And so, the journalists came together to create Deixa Ela Trabalhar. The campaign launched on March 25, according to the BBC, with a powerful video that’s currently circulating the internet airing during a football match at the Maracana stadium — which can hold up to 79,000 people — in Rio de Janeiro.

What we see in the video is people verbally abusing journalists without warning while they’re in the middle of a broadcast. People kissing journalists without warning while they’re in the middle of a broadcast. People groping journalists without warning while they’re in the middle of a broadcast. People assaulting journalists while they’re in the middle of a broadcast.

We see people see something they want, and we see them take it — with no regard not only as to whether the journalists have consented to the behavior, but, moreover, with no regard for the fact that the they’re in the middle of doing their jobs.

“My story is theirs, too. Same stories, different presentations. Women. Women who want to WORK, who can be whatever they want, working WHEREver they want and DESERVE respect. This time, we come together.”

Sexism has long been an issue in Brazil, as well as Latin America more generally, with “machismo” being one of the defining features of the cultural landscape. Described by Nikhil Kumar in the Brown Political Review as “a Latin American cultural analog to patriarchy,” machismo “refers to a set of hyper-masculine characteristics and their value in traditional Latin American society.” Machismo, wrote Kumar, “has slowed progress in changing public opinion on a number of women’s rights issues. The fight for divorce rights, for example, has had mixed success because of widespread societal reluctance.”

According to research, machismo contributes strongly to violence against women, particularly intimate partner and domestic violence. It remains a huge problem in the country; indeed, in 2015, a report by the nonprofit Mapa da Violencia found that Brazil has the fifth highest rate of homicides per 100,000 women, while that same year, data from the Central de Atendimento à Mulher – Ligue (Women’s Assistance Center) found that an incident of violence against women occurred in Brazil an average of once every seven minutes.

What’s more, as Camilla Velloso of the Wilson Center observed in 2017, attitudes towards gender roles remain regressive in Brazil — and that these ideas are “still perpetuated even at the highest levels of the Brazilian government.” Wrote Velloso:

“When President Temer took office in May 2016, he appointed an all-male Cabinet and eliminated the Ministries of Women, Racial Equality and Human Rights. Recently, President Temer took measures to remedy the situation, including appointing two women to his Cabinet and reinstating the ministries albeit under different names. Yet, Brazil lags behind many countries in terms of gender equality: the governments of Syria, Kuwait, Iran and Somalia all have more women in ministerial posts than Brazil. Brazil ranks 154th in number of women in the Legislative Branch, with only 10 percent of women in Congress and 14 percent in the Senate.”

And, of course, there are the anecdotes — the day-to-day experiences recounted by women across the country.

“Unfortunately, I've been harassed by a political scumbag during an interview. In events I lost track of how many men came to me like this. It's unacceptable that they don't respect us, but that way it's even worse.”

For example, a C-suite executive of a Brazilian multinational told The Economist that “earlier in her career, higher-ups would ignore her at meetings until conversations turned to the cosmetics industry." Writing for the BBC in 2016, Silvia Salek recalled an older journalist coming up to her and whispering, “I’m going to eat you all up,” while she was on the job as an economics reporter for a Brazilian newspaper at the age of 22. And, as the moments featured in the Deixa Ela Trabalhar video show, countless reporters deal with men kissing, groping, harassing, and assaulting them while they’re at work — and it’s just considered the norm.

But not anymore.

Support for Deixa Ela Trabalhar has spread across the internet in multiple languages; in addition to the original hashtag, an English equivalent, #LetHerWork, has emerged as well.

“Not harassing someone isn’t a virtue. It’s a must! This wonderful campaign belongs to the women of sports, but this voice belongs to all of us, professionals who have the RIGHT to work in PEACE and with respect! Let us work!”

“The boundaries have been crossed. It's time to say enough.”

“Respect women! It’s not a joke, it’s not cute, it’s not funny! It’s harassment!”

YouTube’s auto-translate feature isn’t great, but one line repeated by multiple journalists in the “Deixa Ela Trabalhar” video stands out: “We are women and professionals,” they say. “We just want to work.”

This is not an unreasonable thing to ask — to have the freedom to do their jobs without being objectified, sexualized, harassed, and assaulted.

And in the #MeToo era, maybe it will finally become reality.