News

Repeal & Replace Is Dead: A Definitive Timeline Of Republicans' Zombie Obamacare Bill That No One Can Kill

On Tuesday, Mitch McConnell announced that the Graham-Cassidy health care bill, which seemed like the last chance for Republicans to repeal and replace Obamacare, would not make it to a vote. It looks like the attempt to dismantle the Affordable Care Act is finally over. But "Repeal and Replace Obamacare" seems like a zombie that will never die. It's failed several times before, and it always comes back. It looks dead, but who can say for sure.

All the way back in 2012, after President Obama won a second term in the White House, Republican Speaker of the House John Boehner declared, "Obamacare is the law of the land," arguing that Republicans would never be able to repeal the law even if they later took the White House back, because the law would take root and go into effect over the course of the next four years. But that didn't convince other Republican politicians, who made continued promises about "Repeal and Replace" consistent talking points of the elections in 2014 and 2016. In February, Boehner again said that Republicans would fail at trying to repeal Obamacare.

Ultimately, it looks like he was right. But here are all the times they tried.

The "Repeal And Delay" That Never Was

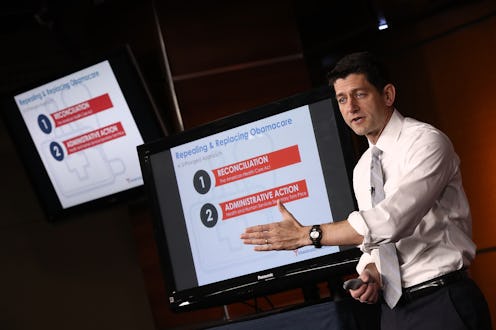

When Paul Ryan took over as Speaker of the House in late 2015, he quickly showed his colleagues that, unlike his predecessor, he wasn't giving up on repealing Obamacare. In January of 2016, Ryan passed a bill using the "budget reconciliation" procedure, which Republicans later tried to use in 2017 to pass their repeal. Under reconciliation, regulations can't be changed, but money can be moved around. So Ryan passed a bill through both houses of Congress that cut all the funding from Obamacare, repealed its taxes, and set the value of the individual mandate — the tax penalty on people not buying insurance — to zero. President Obama vetoed it, but Paul Ryan had demonstrated how to end Obamacare with just 50 votes.

When Donald Trump surprised everyone and won, Paul Ryan found his plan might actually work. He knew Republicans had voted for a straight repeal before, and hoped they could again. His plan morphed into one of "repeal and delay." Knowing it would probably take more than 50 votes to replace the law (since regulations would have to change), Ryan's idea was to defund the law with a 2-year waiting period, and use the impending collapse to force Democrats to the table. Republican health wonks took to this plan, hoping it would give time to agree on an alternative and get Democrats on board for reform.

But Republican lawmakers couldn't quite stomach it. By the time Trump took office, the idea had started to scare them. Defunding Obamacare without removing its regulations would cause health insurance prices to skyrocket, and 32 million people to lose their insurance through the lack of funding.

Senators got cold feet, and the president announced that he wanted repeal and replace "essentially simultaneously," hopefully on the same day. Repeal and Delay, Republicans' first attempt at ending Obamacare, was dead by the time Trump took office, before it had even been born.

The American Health Care Act Gets Hit From All Sides

Republicans had to come up with a replace fast. Both Trump and Speaker Ryan promised an accelerated timeline, with Ryan hoping to accomplish health care, tax reform, and border wall funding all by August. Ryan sat down with advisors in a closed room in the basement of the Capitol, hoping to draft a health care bill that could function well and pass quickly.

But the public was forcing its way into the health care debate. Members of Congress went home to their districts in February to face angry constituents. At town halls, voters yelled at their representatives, frustrated by their attempts to roll back health coverage for millions of people. Groups like Indivisible and MoveOn organized people that voted against Donald Trump into activists that ensured passing his agenda wouldn't be easy, and repealing Obamacare would cost a price.

That price became clear as soon as the American Health Care Act was unveiled. It met immediate and widespread opposition, from Democrats, of course, but also from health care industry groups, the AARP, patient advocates, and even many conservatives. The Congressional Budget Office estimated that the bill would lead to 24 million people losing health care over the next decade. At the same time, prominent conservatives attacked the bill for maintaining the same basic structure as Obamacare, but just with less money.

The House Freedom Caucus, the hard-right group of Republican representatives, bashed the bill, saying it didn't go far enough. Moderates got nervous about the coverage losses the bill would cause. Meanwhile, after being reliably unpopular for the seven years since it had passed, Obamacare gained support from a majority of Americans for the first time. It's stayed there ever since.

President Trump and Speaker Ryan lobbied members of Congress hard. But between conservatives who thought the bill didn't actually repeal Obamacare, and moderates worried about taking insurance away from constituents, there weren't enough votes. On March 24, minutes before the the vote, Republicans pulled the American Health Care Act from the floor of the House. The bill would likely have failed by dozens. On their first real attempt to repeal Obamacare (and to pass legislation under President Trump) Republicans had flopped.

At a press conference that afternoon, Paul Ryan declared, "Obamacare is the law of the land."

"Zombie Trumpcare" Comes Back To Life

AHCA's death was a blow to the Republican agenda; the GOP had broken the promise they had made since 2010. President Trump had struck out the first time at bat. With the divide so large between conservatives and moderates over direction of the bill, it was hard to imagine how a future repeal could build a bridge.

But nevertheless, rumors of "zombie Trumpcare" stuck around, with scattered reports that Republicans were in talks and ready to try again. All of a sudden, the vague rumblings burst forth into concrete action, and Trumpcare was back.

Tom MacArthur, a New Jersey Republican usually considered a moderate, made a deal with the House Freedom Caucus to get them back to the table. Under the MacArthur Amendment, states would be allowed to waive Obamacare regulations, including the ones banning discrimination based on pre-existing conditions. Hardline conservatives got back on board, and moderates, not wanting to be the ones to kill the bill, joined in.

Republicans moved fast, not letting an organized opposition develop like the first time. On May 4, the House passed the new version of the American Health Care Act, without fully knowing its effects, by just two votes. Democrats, believing that this bill could never make it through the Senate, but that voting to take away pre-existing conditions would be brutal to Republicans running for reelection, sang "goodbye" at their colleagues. And Republicans rushed to the White House to celebrate with the president.

Three weeks after the bill was passed, the CBO scored the MacArthur amendment, estimating 23 million people would lose their health coverage, and that without some regulations, the insurance people could buy would be less good. Even before the CBO score, Senate Republicans had announced that they didn't intend to vote for the House bill, preferring to start from scratch and write a better one.

Mitch McConnell Can't Get A Vote

Like Ryan, McConnell felt that an open process in public view could lead to defeat. So rather than going through the normal committee process, he assembled a team of 13 key senators (all male) to devise the bill behind closed doors. Senators like John McCain complained about the secretive process.

On June 22, the Senate unveiled the Better Care Reconciliation Act (BCRA). It kept the basic structure of the AHCA, with heavy cuts to Medicaid, tax cuts, and lower subsidies for health care premiums. The CBO estimated that 22 million people would lose health coverage, and that premiums would initially go up, pushing people out of the market.

It was immediately met with heavy protests from health care activists, especially disability rights advocates and those on Medicaid. The image of people in wheelchairs being arrested and dragged out of the Capitol was the first one much of America saw.

Like with the House bill, the Senate bill was immediately savaged from both sides of the Republican party. Dean Heller, who has a tough reelection in 2018, came out at a press conference with his state's Republican governor bashing the bill. Senators from states that had expanded Medicaid under the ACA got cold feet over the bill's cuts. Meanwhile, conservatives like Mike Lee and Jerry Moran said they couldn't support a bill that preserved Obamacare's structure. With a margin of just two Republican votes in the Senate, McConnell couldn't even get a Motion to Proceed, bringing the bill up to the floor to vote.

The Senate's Voting Spree

McConnell was facing divisions in his caucus over what Obamacare repeal meant. And with senators like Rand Paul still demanding that they vote on the "clean repeal," McConnell eventually decided that the way to move the bill forward would be to set up a vote, with a Motion to Proceed on an unspecified repeal bill, and dare each senator to be the one who blocked Obamacare repeal.

By this point, Sens. Lisa Murkowski and Susan Collins had made it clear they were willing to be that senator, giving Republicans no margin of error. Right before the vote, McCain was diagnosed with a brain tumor. The vote was postponed, knowing that without McCain voting yes on the Motion to Proceed, it couldn't pass.

McCain underwent surgery, and got permission from his doctor to fly back to Washington and vote. On July 25 he voted yes, but then made an impassioned speech about how much the Senate had been degraded by the process, and opposing the specific bill that McConnell intended to vote on. Still, Obamacare repeal was getting closer to passage than it ever had.

In the next few days, the Senate voted on multiple incarnations of Obamacare repeal. First McConnell's BCRA went down, with nine Republicans voting now. Then, the "clean repeal" failed as well, with seven GOP defections.

McCain Kills "Skinny Repeal"

With Republicans unable to agree on what they wanted to replace Obamacare with, they decided to just vote on the one part of Obamacare they all agreed they disapproved of. McConnell introduced the "Skinny Repeal" bill, which didn't touch any of the taxes, spending, or regulations of Obamacare, but got rid of the individual mandate.

Numerous GOP senators said a Skinny Repeal was not enough of an Obamacare repeal, but they were willing to go for it anyway. Senators from Medicaid expansion states, who had opposed bills that cut the program's funding, were willing to entertain this bill. Meanwhile health care experts were warning that Skinny Repeal would create a "death spiral," as not requiring people to buy insurance, but also guaranteeing anyone could buy if they had pre-existing conditions, would mean only sick people would buy insurance, sending prices skyrocketing.

In a press conference, several Republican senators announced that they would vote for Skinny Repeal, but they didn't want it to become law. They wanted assurances from Speaker Ryan that the House wouldn't vote to pass it, but rather come up with a full replacement plan. Ryan promised a conference committee with the Senate before the House would vote, but not that the House would refuse to vote for the bill.

The vote on Skinny Repeal came in the middle of the night. When the Senate took a brief break before the vote, observers noted that McCain arguing with Republican leaders before walking away to speak with Collins and Murkowski, who had already made their no votes clear.

At just before 2 a.m., John McCain walked over to McConnell, and shocked the country by voting no, giving a thumbs down for emphasis. Senators gasped. Skinny repeal was dead.

Outside the Capitol, the crowd of activists who had come to protest Obamacare repeal cheered. In the unlikely fight to save the ACA from a Republican administration that had promised to end it, the resistance had won. And the Trump administration seemed poised to spend its whole first year without a single major legislative accomplishment.

Cassidy And Graham Try One Last Time

Republicans were left defeated after their seven-year promise, and their base was angry. The Senate parliamentarian announced that the reconciliation rules that allowed for just 50 votes in the Senate would expire on Sept. 30. So Sens. Lindsey Graham and Bill Cassidy decided to try one last time.

Under the Cassidy-Graham proposal, most federal health care infrastructure, including the ACA and parts of Medicaid, would be dismantled and turned into block grants of health care funding to states. It would also come with a cut to the budgets of many states that had successfully lowered their uninsured rates (while giving more money to states that hadn't), and making it easier for states to remove protections on pre-existing conditions.

Graham-Cassidy languished in obscurity, until, two weeks before the deadline, Republicans tried for one last Hail Mary. McConnell said he would bring the bill up for a vote if Cassidy and Graham could get 50 votes for it. They started pressuring other Republican senators.

But the pair faced headwinds. Comedian Jimmy Kimmel spent a whole week doing monologues about the bill on his evening talk show, complaining that Cassidy had lied to him when he'd promised to protect pre-existing conditions. Senators like Rand Paul came out against the bill hard, and McCain said he couldn't support it for failing to live up to the Senate's deliberative process. The CBO wasn't given enough time to provide a full analysis of the bill, but wrote that "the number of people with comprehensive health insurance that covers high-cost medical events would be reduced by millions." Susan Collins announced she couldn't support it. The bill, and the last of hope of Republicans to repeal Obamacare this year, was dead.

After the process ended, Graham admitted to reporters that he had been out of his depths on health care policy, and extended that to his entire caucus. "I thought everybody else knew what the hell they were talking about, but apparently not." He said he'd hoped that “these really smart people will figure it out.”

Through this long process, Republicans couldn't seem to agree on what their goals were on health care besides "not Obamacare." It looks like former Republican House Speaker John Boehner's prediction all the way back in 2012 may have been even more true than even he realized. For the foreseeable future, Obamacare is the law of the land.