Books

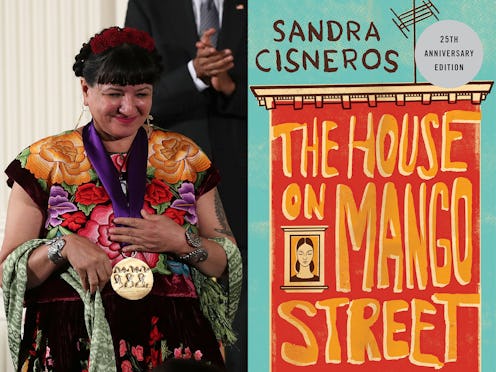

Sandra Cisneros Inspired Me To Live As A Wild Woman

I got to class early and threw my copy of The House on Mango Street by Sandra Cisneros onto my ninth grade English teacher’s desk. Ms. Lopez raised an eyebrow at me.

“This book,” I said, trying to keep my voice from breaking. “I didn’t know we were allowed to write about ourselves.”

I scooped the slim volume back up, holding it to my chest. I didn’t know it then, but the author of those 110 short stories, told from the perspective of a young Mexican-American girl growing up in Chicago, would shift the entire course of my life.

Until that point, I had never seen even a brief glimpse of myself in the books I regularly devoured. I’d traveled the world without ever leaving my border hometown of Chula Vista, California. I’d spent years imagining the scent of English moors; I rattled along in covered wagons traversing the newly stolen nation; I’d collected tin with Francie Nolan in the streets of Brooklyn; I'd spent years with my five best friends, Kristi, MaryAnn, Claudia, Stacy and Dawn. Every time I imagined myself into those stories I had to change the color of my skin, my hair, the language I had learned to love in. But when I imagined myself in House of Mango Street, I didn't have to change much. Who was this Sandra Cisneros woman? I had to find out if she had more books.

"Every time I imagined myself into those stories I had to change the color of my skin, my hair, the language I had learned to love in."

I asked my grandfather to drive me to the mall bookstore after school. There, I found two collections of poetry: My Wicked Wicked Ways and Loose Woman. My Wicked Wicked Ways featured a photograph of Cisneros on the cover: She was seated cross-legged in cowboy boots, and her lips, hoop earrings and wine glass were the only red pictured in the black and white portrait. She leaned forward, in opera gloves and spaghetti straps, as if she was one of my young tias about to tell me something real. My grandfather bought me both books.

If House on Mango Street cut me open, the poetry of Cisneros shattered me. I was expecting more of Esperanza, the narrator of Mango Street. Instead I got Sandra Cisneros herself — wild, raw, and vulnerable on the page in ways that left me buzzing. She wrote of her family, of violence, of travel, of sex, of lovers, of chaos, of loneliness, depression, and obsessive love. She wrote of all things a "good brown girl" from the barrio should not experience, much less put down on the page. When I read her poem “Christ You Delight Me” from Loose Woman and came to the last stanza — Suckle vines, I have to hunker//My cunt close to the earth,//This little pendulum of mine//Ringing, ringing, ringing — I couldn't believe it. A Mexican-American woman, talking like that?

I read her poems to my friends, who shushed me when I got to the sex parts, looking around to make sure I hadn’t been overheard. I grinned and kept reading. I wrote out her poems by hand, trying to find the seeds of power I wanted to plant in my own life. I attempted to imitate her poetry. I imagined myself in a future where I would take lovers, drink too much, smoke cigarettes, rage, and write poetry. I imagined myself traveling like her, bewildering my family members — both living and ancestral.

I wrote out her poems by hand, trying to find the seeds of power I wanted to plant in my own life.

By the time I was in my early 20s, I was well on my way to the raucous living I felt her writing embodied. I took lovers and dumped them unceremoniously. I wept into beer bottles, my dark red lipstick staining the butts of the cigarettes I smoked. I lived gorgeous and dangerous nights in the bars of Tijuana, dancing until dawn with other Mexi-goths and "bad girls." I dropped out of community college, desperate for life to begin outside the confines of a classroom.

I wanted to travel the way Cisneros had, but I was too broke for Europe. Instead, I decided to check out the country a few miles south of where I’d grown up. I bought one of those huge travel backpacks the white kids used for travel, filled it with belongings, and bought a one-way ticket to Mexico City, much to the alarm of my parents and extended family.

I lived gorgeous and dangerous nights in the bars of Tijuana, dancing until dawn with other Mexi-goths and 'bad girls.'

Gods, I made mistakes. And yet those mistakes didn’t unmoor me, because I had an anchor: If Cisneros had done it, why couldn’t I? I carried a journal with me, spilling my regrets into it, my fears, my desperate loneliness. I started calling myself a writer. For a year and a half, I put down roots in San Miguel de Allende, a town in central Mexico known for its artistic ex-pat community. (Curiously, it is also the town where Cisneros now lives.) The Mexicans there were accustomed to American ways of living and didn’t judge me as harshly. I found a spiritual where I could write, paint, and build a life.

When I eventually came home, I was a different woman. The desperation was mostly worn out of me. I started to write seriously and share my work. I trembled at open mics as I read the poems I had written in Mexico. I met a community of Latinx writers and artists who believed in and supported me. In 2005, I took one of the poems I’d written and sent it off to a literary journal, certain it would be rejected. I was gobsmacked when the editor wrote me back, accepting the poem for publication. Seeing my name in print for the first time — my little poem singing from the page — I cried in joy. I had done it. I was a brown girl publishing dirty poems for the world to read, just like Cisneros.

Over the years, I’ve fallen in love with the writings of other women of color but none have ever affected me as deeply as Cisneros did when I was 14 years old. She came to me at the exact right moment in my life. I imagine my life probably would have been a lot saner and safer had I not been assigned The House on Mango Street by my teacher. I haven’t lived the life my parents would have ever wished for me, but by breaking free from those expectations, I liberated myself — and my parents. They started traveling, embracing their own wildness, meeting my sisters in me in ours. They’re my favorite people to hang out with on the planet. My younger cousins have thanked me for being the black sheep, the wanderer, the old maid. By living my life as I wanted, I made it easier for others to do the same.

I imagine my life probably would have been a lot saner and safer had I not been assigned The House on Mango Street by my teacher.

These days my stories are my own. They are by the strange little life I’ve crafted for myself. I weave mythology into my tales. My stories feature women who roam the night skies on wings, Succubi who destroy sexual predators women unafraid of their power.

I owe it to Sandra Cisneros. She showed me that I too could believe, crumble, wander, rise.

For more Latinx Heritage Month content on Bustle, click here.