Books

Start Reading From This YA Novel For Fans For 'The Handmaid's Tale' & 'The Power'

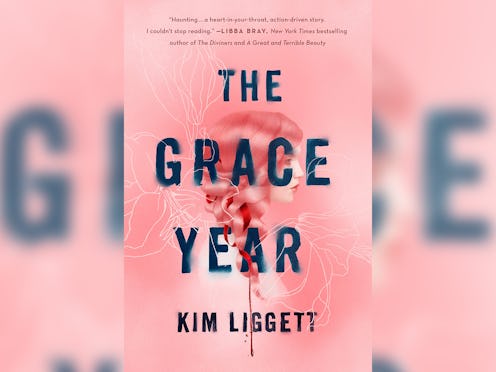

If you're a YA fan who loves books like The Handmaid's Tale, The Power, and Vox, I've got a sneak peek at a book you're going to love. The Grace Year is Kim Liggett's new YA novel about teenage girls who are sent away to avoid bewitching men with their magic, and it's a must-read. It's not out until this fall, but Bustle is pleased to reveal the cover for you below, and to offer an exclusive excerpt from The Grace Year for you to enjoy.

The Grace Year centers on Tierney, a 16-year-old girl about to be sent away for the titular event. No one talks about what happens during the grace year, but girls know that it seals their fates. Those who do not leave their towns and villages with promises of marriage from the boys their age are sent to work in the labor houses, and Tierney has done all she can to make sure that no boy wants to give her a veil before she departs.

Kim Liggett's new novel comes with an excellent recommendation from A Great and Terrible Beauty author Libba Bray, who calls it "a heart-in-your-throat, action-driven story" that she "couldn't stop reading." The Grace Year doesn't hit stores until Sep. 17, but you can see the cover and read an exclusive excerpt below.

EXCERPT: The Grace Year

No one speaks of the grace year.

It’s forbidden.

We’re told we have the power to lure grown men from their beds, make boys lose their minds, and drive the wives mad with jealousy. They believe our very skin emits a powerful aphrodisiac, the potent essence of youth, of a girl on the edge of womanhood. That’s why we’re banished for our sixteenth year, to release our magic into the wild before we’re allowed to return to civilization.

But I don’t feel powerful.

I don’t feel magical.

Speaking of the grace year is forbidden, but it hasn’t stopped me from searching for clues.

We’re told we have the power to lure grown men from their beds, make boys lose their minds, and drive the wives mad with jealousy.

A slip of the tongue between lovers in the meadow, a frightening bedtime story that doesn’t feel like a story at all, knowing glances nestled in the frosty hollows between pleasantries of the women at the market. But they give away nothing.

The truth about the grace year, what happens during that shadow year, is hidden away in the tiny slivers of filament hovering around them when they think no one’s watching. But I’m always watching.

The slip of a shawl, scarred shoulders bared under a harvest moon.

Haunted fingertips skimming the pond, watching the ripples fade to black.

Their eyes a million miles away. In wonderment. In horror.

I used to think that was my magic — having the power to see things others couldn’t — things they didn’t even want to admit to themselves. But all you have to do is open your eyes.

My eyes are wide open.

***

Autumn

I follow her through the woods, a well-worn path I’ve seen a thousand times. Ferns, lady-slipper, and thistle, the mysterious red flowers dotting the path. Five petals, perfectly formed, like they were made just for us. One petal for the grace year girls, one petal for the wives, one for the laborers, one for the women of the outskirts, and one for her.

The girl looks back at me over her shoulder, giving me that confident grin. She reminds me of someone, but I can’t place the name or the face. Maybe something from a long-forgotten memory, a past life, perhaps a younger sister I never knew. Heart-shaped face, a small red strawberry mark under her right eye. Delicate features, like mine, but there’s nothing delicate about this girl. There’s a fierceness in her steel-gray eyes. Her dark hair is shorn close to her scalp. A punishment or a rebellion, I cannot say. I don’t know her, but strangely enough, I know that I love her. It’s not a love like my father has for my mother, it’s protective and pure, the same way I felt about those robins I cared for last winter.

She reminds me of someone, but I can’t place the name or the face. Maybe something from a long-forgotten memory, a past life, perhaps a younger sister I never knew.

We reach the clearing, where women from all walks of life have gathered — the labor houses, the wives, the maids, the outskirts — the tiny red flower pinned above their hearts. There’s no bickering or murderous glares; everyone has come together in peace. In unity. We are sisters, daughters, mothers, grandmothers, standing together for a common need, greater than ourselves.

“We are the weaker sex, weaker no more,” the girl says.

The women answer with a primal roar.

But I’m not afraid. I only feel a sense of wonder and pride. The girl is the one. She’s the one who will change everything, and somehow, I’m a part of all this.

“This path has been paved with blood, the blood of our own, but it was not in vain. Tonight, the grace year comes to an end.”

As I expel the air from my lungs, I find myself not in the woods, not with the girl, but here, in this stifling room, in my bed, my sisters glaring down at me.

“What did she say?” my older sister Ivy asks in shock, her cheeks ablaze.

“Nothing,” June replies, squeezing Ivy’s wrist. “We heard nothing.”

As my mother enters the room, my little sisters, Clara and Penny, poke me out of bed. I look to June to thank her for quelling the situation, but she won’t meet my gaze. She won’t or she can’t. I’m not sure what’s worse.

We’re not allowed to dream. The men believe it’s a way we can hide our magic. Having the dreams would be enough to get me punished, but if anyone ever found out what the dreams were about, it would mean the gallows.

My sisters lead me to the sewing room, fluttering around me like a knot of bickering sparrows. Pushing. Pulling.

We’re not allowed to dream. The men believe it’s a way we can hide our magic.

“Ease up,” I gasp as Clara and Penny yank on the corset strings with a little too much glee. They think this is all fun and games. They don’t realize that in a few short years, it will be their turn. I swat at them. “Don’t you have anyone else to torture?”

“Stop your fussing,” my mother says, taking out her frustration on my scalp as she finishes my braid. “Your father has let you get away with murder all these years, with your mud-stained frocks, dirt under your nails. For once, you’re going to know what it feels like to be a lady.”

“Why bother?” Ivy flaunts her growing belly in the looking glass for all of us to see. “No one in their right mind would give a veil to Tierney.”

“So be it,” my mother says as she grabs the corset strings and pulls even tighter. “But she owes me this.”

I was a willful child, too curious for my own good, head in the clouds, lacking propriety . . . among other things. And I will be the first girl in our family to go into her grace year without receiving a veil.

My mother doesn’t need to say it. Every time she looks at me I feel her resentment. Her quiet rage.

“Here it is.” My oldest sister, June, slips back into the room, carrying a deep-blue raw-silk dress with river-clam pearls adorning the shawl neckline. It’s the same dress she wore on her veiling day four years ago. It smells of lilac and fear. White lilac was the flower her suitor chose for her—the symbol of early love, innocence. It’s kind of her to let me borrow it, but that’s June. Not even the grace year could take that away from her.

All the other girls in my year will be wearing new dresses today with frills and embroidery, the latest style, but my parents knew better than to waste their resources on me. I have no prospects. I made damn sure of that.

There are twelve eligible boys in Garner County this year — boys born into families that have standing and position. And there are thirty-three girls.

Today, we’re expected to parade around town, giving the boys one last viewing before they join the men in the main barn to trade and barter our fates like cattle, which isn’t that far off considering we’re branded at birth on the bottom of our foot with our father’s sigil. When all the claims have been made, our fathers will deliver the veils to the awaiting girls at the church, silently placing the gauzy monstrosities on the chosen ones’ heads. And tomorrow morning, when we’re all lined up in the square to leave for our grace year, each boy will lift the veil of the girl of his choosing, as a promise of marriage, while the rest of us will be completely dispensable.

“I knew you had a figure under there.” My mother purses her lips, causing the fine lines around her mouth to settle into deep grooves. She’d stop doing it if she knew how old it made her look. The only thing worse than being old in Garner County is being barren. “For the life of me I’ll never understand why you squandered your beauty, squandered your chance to run your own house,” she says as she eases the dress over my head.

My arm gets stuck and I start pulling.

“Stop fighting or it’s going to — ”

The sound of ripping fabric causes a visible heat to creep up my mother’s neck, settling into her jaw. “Needle and thread,” she barks at my sisters, and they hop to.

I try to hold it in, but the harder I try, the worse it gets, until I burst out laughing. I can’t even put on a dress right.

“Go ahead, laugh all you want, but you won’t think it’s so funny when no one gives you a veil and you come back from the grace year only to be sent straight to one of the labor houses, working your fingers to the bone.”

“Better than being someone’s wife,” I mutter.

“Never say that.” She grabs my face in her hands, and my sisters scatter. “Do you want them to think you’re a usurper? To be cast out? The poachers would love to get their hands on you.” She lowers her voice. “You cannot bring shame on this family.”

I try to hold it in, but the harder I try, the worse it gets, until I burst out laughing. I can’t even put on a dress right.

“What’s this about?” My father tucks his pipe into his breast pocket as he makes a rare appearance in the sewing room. Mother quickly composes herself and mends the tear.

“No shame in hard work,” he says as he ducks under the eave, kissing my mother on the cheek, reeking of iodine and sweet tobacco. “She can work in the dairy or the mill when she returns. That’s entirely respectable. You know our Tierney’s always been a free spirit,” he says with a conspiratorial wink.

I look away, pretending to be fascinated by the dots of hazy light seeping in through the eyelet curtains. My father and I used to be thick as winter wool. People said he had a certain twinkle in his eye when he spoke of me. With five daughters, I guess I was the closest thing to a coveted son he’d ever get. On the sly, he taught me how to fish, how to handle a knife, how to take care of myself, but everything’s different now. I can’t look at him the same way after the night I caught him at the apothecary, doing the unspeakable. Clearly, he’s still trying for a prized son, but I always thought he was better than that. As it turns out, he’s just like the rest of them.

From The Grace Year by Kim Liggett. Copyright © 2019 by the author and reprinted by permission of Wednesday Books.