News

One Thing Not To Forget About Steven Avery's Case

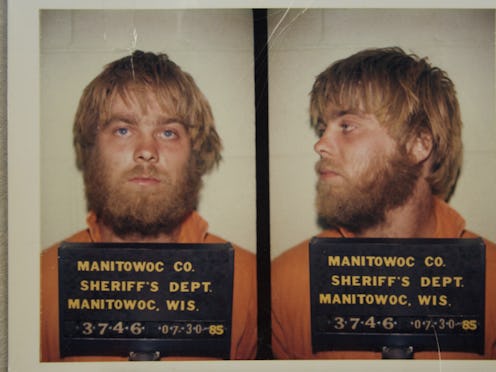

Given the attention Making A Murderer has received, it's no wonder that Steven Avery's case is mesmerizing the masses. How could a man be charged of a crime, be convicted, and have DNA exonerate him, just to be charged and convicted for a totally different crime just over two years later? Given that Friday is the 9-year anniversary of his conviction, the one thing you shouldn't forget about Steven Avery's case is how common what happened to him during this first case actually is. According to the National Registry of Exonerations, last year, 149 people were exonerated in the United States, which is more than ever before — 58 (also a record) were exonerated of homicide specifically.

That's in just one year; 58 is a huge number. Since 1989, when the National Registry of Exonerations, a project of the University of Michigan Law School, has counted 1,753 in the United States. One of those is Steven Avery. He was exonerated in 2003 when DNA evidence proved he had not committed the sexual assault he had been charged with. But that doesn't mean he will necessarily be exonerated again. Although Steven Avery was ultimately convicted in the murder of Teresa Halbach, he is still adamant that he did not commit the crime. A look at the statistics behind convictions show some startling similarities to the case against Avery.

In 2015, 76 percent of exonerations stemmed from police misconduct that led to a wrongful conviction, the National Registry of Exonerations reported. Avery sued the Manitowoc Sheriff's Department after his first wrongful conviction in the sexual assault case. While he was spending his 18 years behind bars, there was a chance people on the outside knew that he wasn't the guy, Avery's lawyers claimed. Manitowoc County Sheriff’s Department’s Sgt. Andrew Colborn and Lt. James Lenk were suspected of discovering evidence that suggested Avery's innocence in the case in the 1990s. Colborn didn't officially report the phone call until 2003. He claimed he referred the call to the sheriff's detective unit, and he and Lenk adamantly deny any wrongdoing in the case.

This was part of Avery's civil case against the department, which was beginning right around the time he was accused of Halbach's murder. Both Colborn and Lenk were named in the $36 million suit. It was settled out of court after Avery became a suspect and needed to pay legal bills. Those are the same two officers have been accused of planting evidence at the scene. The Manitowoc County Sheriff’s Department has also vehemently denied any wrongdoing, but that still seems to be the route Avery's lawyer, Kathleen Zellner, will take.

Another correlation between the typical exoneration and the Avery case is that there was a confession that raised some questions. Believe it or not, 38 percent of the 58 people exonerated of homicide last year had falsely confessed, according to the National Registry of Exonerations. "Most were under 18 or suffered from mental illness or intellectual disability, or both," the registry's 2015 report said.

When Avery's nephew Brendan Dassey was interrogated and ultimately confessed to raping Halbach with his uncle and disposing of her body, he was just 16. Making A Murderer described him as having a learning disability and not being able to read above a fourth-grade level. From the very beginning, Avery has claimed Dassey was coerced. Dassey's lawyers said he could not handle the pressure of the interrogation tactics. However, the Manitowoc County Sheriff's Department says the confession followed standard protocol.

"Something wrong happened here," said Laura Nirider, one of Dassey's lawyers, an attorney at Bluhm Legal Clinic at the Northwestern University School of Law in Chicago. "Everybody has a right to have a loyal attorney. His confession was fictitious."

Of course correlation does not mean causation — and there's a good chance Avery and Dassey will not be released. Even if you're up-to-date on every Reddit thread on the subject, there's no way to know. And even given the increasingly shocking tweets from Zellner, you can't know what evidence she and Dassey's lawyers would present in a courtroom, if they event get there. Twitter cannot replace a judge and jury. Even the filmmakers have said Avery and Dassey face "incredible odds."

But the fact that the 58 people exonerated in 2015 wrongfully spent a combined 969 years behind bars should remind you that there are still people in prison who are being failed by a flawed system.

Image: Making A Murderer/Netflix