Books

We Are All Ramona Quimbys

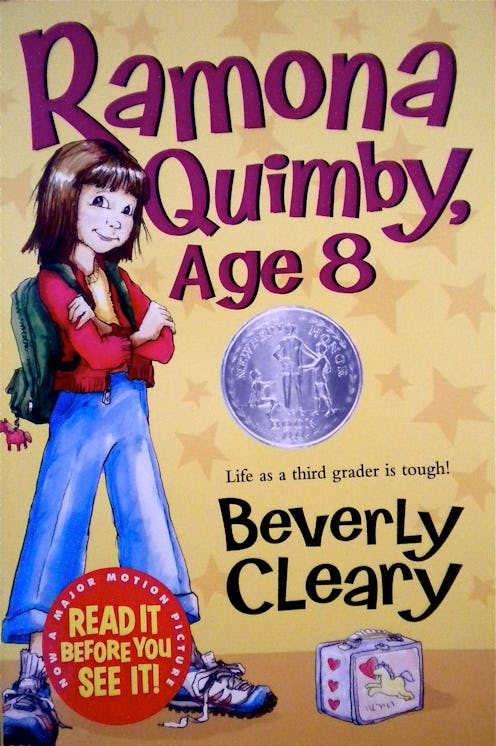

During college, my professor asked us to bring in a book that we thought was a great example of how to write about women’s lives. My peers brought in copies of Zami, The Second Sex, and The Well of Loneliness, among others. I brought in Ramona, Age 8.

Ramona Quimby’s big break came in 1968, when Beverly Cleary moved her into the spotlight with Ramona, The Pest . (She had previously appeared as a secondary character in the Henry Huggins series and in Beezus and Ramona.) Her childhood was not dissimilar to mine and many others' (though I was always especially proud of a shared 3rd grade throwing-up-in-school experience).

Ramona is a totally ordinary girl, and the books that feature her are, well… kind of dull. There are no crazy plot twists, no insurmountable odds to overcome. Her childhood isn’t glamorous (her parents struggle to make ends meet) but it isn’t difficult, either: she is well looked-after and loved. Really, the only thing Ramona has to work through is herself. She’s a child annoyed with the limits of childhood — not being taken seriously by her family and having to follow other people’s rules — but is still very much a child (and very much a youngest at that), overly concerned with fairness, perpetually cranky and endearingly sweet; when she gets a new set of pajamas, she loves them so much she wears them under her clothes to school and is furious when she thinks her teacher has betrayed her trust by telling Mrs. Quimby. She also relishes in her role as a kid when she needs to, feeling comforted and relieved when her mother picks her up from class after she throws up. Ramona makes mistakes and plenty of messes; though she wants to be older, she isn’t yet.

But just because she’s a little girl doesn’t mean she isn’t a big literary figure.

That’s the genius of Cleary’s depiction of girlhoods — she knows that girlhoods are often awkward exercises in wanting fairness, overcoming shyness, living partially in a dream world, and acting like a lunatic with your friends. They’re complex years of wanting to be older than you are but secretly being glad you aren’t and thinking you understand the mysterious world of adults only to realize that you have no understanding, not at all. That’s the reason Ramona books are still read today, and that’s the reason we still see Ramonas all over the place.

She’s aged a few years, as Kristy, the tomboy, in The Baby-Sitters Club; she’s pre-death, normal-kid Susie in The Lovely Bones, childishly excited at the prospect of high school; she’s Lee in Prep, who left her parents far too soon and thinks she understands complicated race and class politics; she’s Lena Dunham (or, to be fair, she’s Dunham’s television and essay personae), the young woman who idealizes adulthood but can’t quite get there on her own.

These aren’t particularly interesting characters (posthumous Susie being the exception), but neither was Ramona, and neither was I, which is why I loved her then and why I love her still. Beverly Cleary gave all the girls without an exciting story to tell a chance to tell the stories inside themselves; she showed generations of women that their very average lives are worthy of attention and celebration. She showed more than a few writers, at least — I wonder if we’d have Bossypants, Is Everyone Hanging Out Without Me? or I Was Told There’d Be Cake without her influence.

I was prepared to have a full-blown Ramona moment that day when I brought my worn book in to class — I’m not a good public speaker, so I worried I’d sound silly, especially considering that my class was full of seniors whom I totally idolized and relentlessly Facebook-stalked. My worry got worse as each classmate presented classic feminist text after classic feminist text. But when I finally (and reluctantly) had my turn to discuss the book I’d brought in, one of the seniors who was at the very top of my girl-crush list yelled “YESSSSSSSSSS!” I felt a particular kinship with Ramona at that moment, and realize now that I did have a full-blown Ramona moment then, albeit the good kind: the everyday triumph, the glory of a class period well-spent, the high of an outcome being better than expected, and the most ordinary victory of all — not wanting to make a fool out of yourself and getting, instead, a handful of new friends and a check-plus on your assignment.