Life

Men And Women Experience Jealousy Differently

Ugh, jealousy. Occasionally it might be a good thing—the thing that gives us the push we need to get something done or move forward—but more often than not, it’s a festering, nasty emotion, one that makes us unhappy and restless when we’d be better served by feeling grateful for what we have. Most of us can’t escape it, even when we know it’s irrational or pointless: A 2014 survey by WhatsYourPrice, for example, found that among the more than 105,000 singles they questioned, jealousy was the third most common reason for their most recent breakups. We all experience jealousy in different ways and for different reasons, but a recent academic study shows that gender, as well as sexual orientation, has a significant effect on how and why people are jealous.

In December of 2014, psychologists David A. Frederick and Melissa R. Fales, from Chapman University and UCLA, respectively, published a study in the Archives of Sexual Behavior considering how heterosexual, homosexual, and bisexual men and women experience the big green monster (and I’m not talking about the Hulk). The results of the study are rather surprising in that they seem to confirm long-running stereotypes that men are more concerned about sexual infidelity, whereas women are more bothered emotional infidelity (at least, this is the case when it comes to straight couples). The research team surveyed 63,894 participants (a number which distinguishes this study from earlier work that studied much smaller groups).

As Frederick and Fales describe, participants were asked to imagine two scenarios: “their partners having sex with someone else (but not falling in love with them) or their partners falling in love with someone else (but not having sex with them)”. Frederick and Fales found that 54 percent of heterosexual men reported being upset by the idea of sexual infidelity, as opposed to 35 percent of women. Conversely, 65 women said they would be upset by emotional infidelity, as opposed to 46 percent of men.

Frederick and Fales hypothesize that these results suggest an evolutionary component to jealousy. The theory goes that men are concerned about sexual infidelity because a woman’s infidelity could result in children that aren’t genetically related to her partner, prompting him to invest time and resources in children that won’t pass on his genetic material. (God, this is getting bleak.) In contrast, women (who already know that their kids carry their genetic material) need long-term support from their male partners in the raising of children; therefore, emotional attachments to others pose the most significant threat to the stability of the home life. (Actually, this is extremely interesting; Don't ever forget that we're animals, you guys.)

Another significant finding of the study is that this gender split only holds true in the case of heterosexual couples. Bisexual, gay, and lesbian participants showed no major difference in how they would react to sexual infidelity, and heterosexual males were the only demographic to consistently report that they would be more upset by sexual than emotional infidelity. (I'm just gonna let that set in for a minute...okay, we ready to move on?) This result would seem to support Frederick and Fales’s evolutionary theory, since gay men would not need to worry about paternity with their male partners (though it should be noted that bisexual men with female partners also didn’t have heightened jealousy of sexual infidelity).

Frederick and Fales’s evolutionary theory is an interesting way of approaching what often seems like a destructive and completely irrational emotion; however, it’s important to remember that there are lots of cultural factors that could also contribute to these results. It’s incredibly difficult to separate these cultural factors (the “nurture”) from more deeply-ingrained behaviors (the “nature”). For example, although it makes sense from an evolutionary standpoint that males would be more susceptible to sexual jealousy, it also makes sense that our culture, in which women are consistently figured as sexual property and masculinity is aligned with sexual prowess, embeds these same tendencies in men from a young age. While it’s good to try to figure out how our jealousies develop and where they come from, that doesn’t mean that we shouldn’t try to curb these feelings and seek out more productive ways of dealing with insecurity.

Evolution’s no excuse for turning into a green-eyed rage-ball, after all.

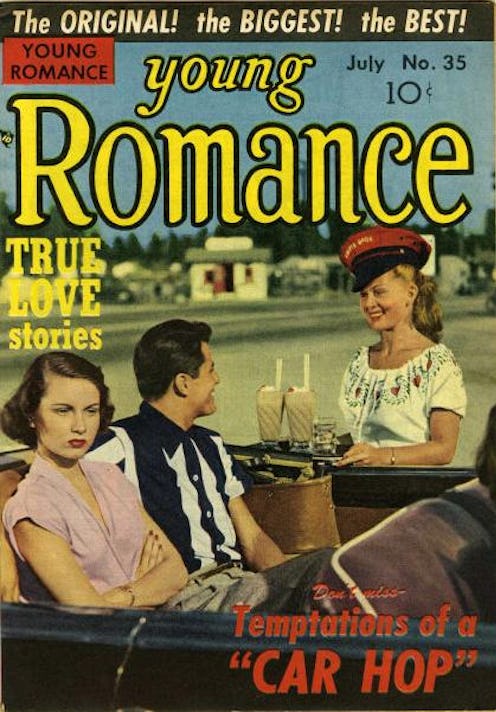

Images: Wikimedia; Giphy (3)