Books

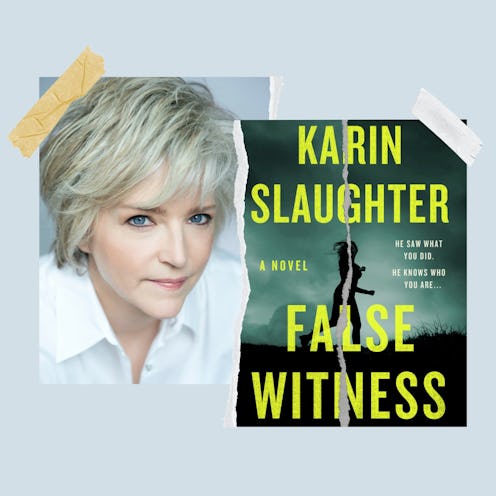

Dying To Continue Karin Slaughter’s False Witness? Keep Reading Right Here.

Read the third and final installment in Bustle’s serialization below.

Over the last two weeks, Bustle has published exclusive looks at the prologue and opening chapters of Karin Slaughter’s False Witness. Now, we’re releasing the final excerpt in our serialization, which comprises chapters four and five from the much-anticipated book.

Coming to stores on July 20, Slaughter’s new standalone novel centers on sisters Leigh and Callie — a successful Atlanta defense attorney and her ne’er-do-well sister — as they confront the darkest secrets from their shared past.

Trigger Warning: This piece contains descriptions of sexual assault, child sexual abuse, and the production of child sexual abuse materials.

Earlier installments of False Witness published on Bustle introduced readers to Leigh and Callie: survivors of abuse, who killed and dismembered Callie’s rapist — a man who had distributed videotapes of himself sexually abusing her. Callie was paid to babysit Trevor, the rapist’s young son, but the boy was half-drunk on NyQuil the night his father died. Now, Trevor’s back in Leigh’s orbit as her latest client, fighting his own rape allegation. Leigh’s convinced that he knows what she and her sister did all those years ago, and now she’s got to get Callie to safety before it’s too late.

Keep scrolling to read Bustle’s final excerpt from Karin Slaughter’s False Witness, and pre-order your copy today, ahead of the novel’s July 20 release.

SPRING 2021

4

“Let’s see what’s going on with Mr. Pete.” Dr. Jerry started examining the cat, tenderly palpating a swollen joint. At fifteen years old, Mr. Pete was roughly the same age in human years as Dr. Jerry. “Maybe some underlying arthritis? Poor fella.”

Callie looked down at the chart in her hands. “He was taking a supplement, but developed constipation.”

“Oh, the injustices of old age.” Dr. Jerry hooked his stethoscope into his ears, which were almost as hairy as Mr. Pete’s. “Could you —”

Callie leaned down and blew air in Mr. Pete’s face, trying to stop his purring. The cat looked annoyed, and Callie could not blame him. He’d gotten his paw hooked in the frame of the bed when he was trying to jump down for breakfast. It could happen to anybody. “That’s a good boy.” Dr. Jerry stroked Mr. Pete’s scruff. He told Callie, “Maine Coons are magnificent animals, but they tend to be the linebackers of the feline world.”

Callie flipped back through the chart to start taking notes. “Mr. Pete is a neutered male of portly stature who presented with right forelimb lameness, having fallen from the bed. Physical exam revealed mild swelling but no crepitus or joint instability. Bloodwork was normal. Radiographs showed no obvious fracture. Start on buprenorphine and gabapentin for pain management. Recheck in one week.”

She asked, “Bupe is point-oh-two m-g/k-g q8h for how many days?”

“Let’s start with six days. Give him one for the road. No one likes car trips.”

Callie carefully wrote his instructions into the chart as Dr. Jerry placed Mr. Pete back into his carrier. They were still on Covid protocols. Mr. Pete’s mother was currently sitting in her car outside in the parking lot.

Dr. Jerry asked, “Anything else from the medicine cabinet?” Callie went through the stack of charts on the counter. “Aroo Feldman’s parents report an increase in pain.”

“Let’s send home some more Tramadol.” He signed off on a new script. “Bless their hearts. Corgis are such assholes.”

“Agree to disagree.” She passed another chart. “Sploot McGhee, greyhound meets motor vehicle. Cracked ribs.”

“I remember this lanky young man.” Dr. Jerry’s hands shook as he adjusted his glasses. She saw his eyes barely move as he pretended to read the chart. “Methadone if they bring him in. If he’s not up to the visit, send home a fentanyl patch.”

They went through the rest of the big dogs — Deux Claude, a Great Pyrenees with patellar displacement. Scout, a German Shepherd who’d nearly impaled himself on a fence. O’Barky, an Irish wolfhound with hip dysplasia. Ronaldo, an arthritic Labrador who weighed as much as a twelve-year-old child.

Dr. Jerry was yawning by the time Callie got to the cats. “Just do the usual, my friend. You know these animals as well as I do, though be careful with that last one. Never turn your back on a calico.”

She smiled at his playful wink.

“I’ll give Mr. Pete’s human a call, then take my executive time.” He winked again, because they both knew he was going to take a nap. “Thank you, angel.”

Callie kept up her smile until he turned away. She looked down, pretending to read the charts. She didn’t want to watch him shuffle down the hallway like an old man.

Dr. Jerry was a Lake Point institution, the only vet in the area who took EBT cards in exchange for services. Callie’s first real job had been at this clinic. She was seventeen. Dr. Jerry’s wife had just passed away. He had a son somewhere in Oregon who only called on Father’s Day and Christmas. Callie was all he had left. Or maybe Dr. Jerry was all that she had left. He was like a father figure, or at least like what she’d heard father figures were supposed to be. He knew Callie had her demons but he never punished her for them. It was only after her first felony drug conviction that he’d stopped pushing her to go to vet school. The Drug Enforcement Agency had a crazy rule against giving prescription pads to heroin addicts.

She waited for his office door to close before starting down the hallway. Her knee made a loud pop as she extended her leg. At thirty-seven, Callie was not that much better off than Mr. Pete. She pressed her ear to the office door. She heard Dr. Jerry talking to Mr. Pete’s owner. Callie waited a few more minutes until she heard the creaks from the old leather couch as he laid down for his nap.

She let out a breath that she’d been holding. She took out her phone and set the timer for one hour.

Over the years, Callie had used the clinic as a junkie vacation, cleaning herself up just enough so that she could work. Dr. Jerry always took her back, never asked her where she’d been or why she’d left so abruptly the last time. Her longest stretch of sobriety had been too many years ago to count. She’d lasted eight full months before she’d fallen back into her addiction.

This time wouldn’t be any different.

Callie had given up on hope ages ago. She was a junkie, and she would always be a junkie. Not like people in AA who quit drinking but still said they were alcoholics. Like somebody who was always, always going to return to the needle. She wasn’t sure when she had come into this acceptance. Was it her third or fourth time in rehab? Was it the eight months of sobriety she’d broken because it was Tuesday? Was it because it was easier to have these maintenance spells when she knew they were only temporary?

Currently, only a sense of usefulness was keeping her on the somewhat straight and narrow. Because of a series of mini-strokes in the past year, Dr. Jerry had shortened the clinic hours down to four days a week. Some days were better for him than others. His balance was off. His short-term memory was unreliable. He often told Callie that without her, he wasn’t sure he’d be able to work one day, let alone four.

She should feel guilty for using him, but she was a junkie. She felt guilty about every second of her life.

Callie pulled out the two keys to open the drug cabinet. Technically, Dr. Jerry was supposed to keep the second key, but he trusted her to accurately log in the controlled substances. If she didn’t, then the DEA could start snooping around, matching invoices to dosages to charts, and Dr. Jerry could lose his license and Callie could go to jail.

Generally, addicts made the Drug Enforcement Agency’s job easier because they were desperately stupid for their next fix. They OD’d in the waiting room or had a heart attack on the toilet or snatched as many vials as they could shove into their pockets and started running for the door. Fortunately, Callie had figured out through big trials and little errors how to steal a steady supply of maintenance drugs that kept her from getting dope sick.

Every day, she needed a total of either 60 milligrams of methadone or 16 milligrams of buprenorphine to ward off the vomiting, headaches, insomnia, explosive diarrhea, and crippling bone pain that came from heroin withdrawal. The only rule Callie had ever been able to stick to was that she never took anything an animal needed. If her cravings got bad, she dropped her keys back through the mail slot in the door and stopped showing up. Callie would rather die than see an animal suffer. Even a corgi, because Dr. Jerry was right. They could be real assholes.

Callie let herself stare longingly at the stockpiles in the cabinet before she started taking down vials and pill bottles. She opened the drug logbook next to the stack of charts. She clicked her pen. Dr. Jerry’s clinic was a small operation. Some vets had machines where you had to use your fingerprint to open the drug cabinet, and your fingerprint had to match the chart and the chart had to match the dosage and that was tricky, but Callie had been working for Dr. Jerry on and off for nearly two decades. She could beat any system in her sleep.

This was how she did it: Aroo Feldman’s parents had not asked for more Tramadol, but she’d logged the request into the chart anyway. Sploot McGhee would get the fentanyl patch because cracked ribs were awful and even a haughty greyhound deserved peace. Likewise, Scout, the idiotic German Shepherd who’d chased a squirrel over a wrought iron fence, would get all the medication he needed.

O’Barky, Ronaldo, and Deux Claude were imaginary animals whose owners had transient addresses and non-working phone numbers. Callie had spent hours giving them backstories: teeth cleanings, heartworm meds, swallowed squeaky toys, unexplained vomiting, general malaise. There were more fake patients — a bull mastiff, a Great Dane, an Alaskan Malamute, and a smattering of sheepdogs. Pain meds were dosed based on weight, and Callie made sure to pick breeds that could go north of one hundred pounds.

Freakishly large Borzois weren’t the only way to game the system. Spoilage was a reliable fallback. The DEA understood that animals were wriggly and a lot of times half an injection could end up squirted into your face or onto the floor. You recorded that as spoiled in the book and you went about your day. In a pinch, Callie could drop a vial of sterile saline in front of Dr. Jerry and get him to cancel it out in the log as methadone or buprenorphine. Or sometimes, he would forget what he was doing and make the change himself.

Then there were the easier options. When the visiting orthopedic surgeon came every other Tuesday, Callie prepared bags of fluids with fentanyl, a synthetic opioid that was so strong it was generally only prescribed for advanced cancer pain, and ketamine, a dissociative anesthetic. The trick was to siphon off enough of each drug so that the patient was still comfortable for surgery. Then there was pentobarbital, or Euthasol, which was used to euthanize sickly animals. Most doctors pulled three to four times what was actually needed because no one wanted it to not work. The taste was bitter, but some recreational users liked to cut it with rum and zonk out for the night.

Because there weren’t enough St. Bernards and Newfoundlands in Lake Point to justify Callie’s maintenance doses, she sold or traded what she could in order to buy methadone. The pandemic had been amazing for drug sales. The cost of your average high had gone through the roof. She considered herself the Robin Hood of drug dealers, because most of the money was returned to the clinic so that Dr. Jerry could keep the doors open. He paid her cash every Friday. He was always astonished by the large number of crumpled, small bills in the lockbox.

Callie opened Mr. Pete’s chart. She changed the six to an eight, then drew up the buprenorphine syringes for oral use. She didn’t tend to steal from cats because they were relatively small and didn’t give a big bang for the buck like a beefy rottweiler. Knowing cats, they probably kept their weight down for that very reason.

She stuck the syringes in a plastic bag, then printed out the label. The rest of the booty went into her backpack in the breakroom. Callie’s sister had told her a long time ago that she spent more brainpower doing the wrong thing than she would have to expend doing things right, but fuck her sister; she was one of those bitches who could go on a coke binge to study for the LSAT and never think about coke ever again.

Callie could look at a beautiful green tablet of Oxy and dream about it for the next month.

She wiped her mouth, because now she was dreaming about Oxy.

Callie found Mr. Pete in his carrier. She squirted a syringe of pain meds into his mouth. He sneezed twice, then gave her a very nasty look as she put on a mask and gown so she could take him out to the car.

She left on the mask while she cleaned the clinic. The floors were concave from years of Dr. Jerry’s Birkenstocks padding from exam room to exam room, then back to his office. The low ceiling was water-stained. The walls were covered in buckled paneling. There were faded photographs of animals plastered everywhere. Callie used a duster to knock off the grime. She got on her hands and knees to clean the two exam rooms, then moved on to surgery, then the kennel. They didn’t usually board animals, but there was a kitten named Meowma Cass that Dr. Jerry was taking home to bottle-feed and a calico who’d come in yesterday with a string hanging out of his butt. The emergency surgery had been too costly for the owners, but Dr. Jerry had spent an hour removing the string from the cat’s intestines anyway.

Callie’s alarm went off on her phone. She checked her Facebook, then scrolled through Twitter. The majority of her follows were animal-specific, like a New Zealand zoo keeper who was obsessed with Tasmanian devils and an eel historian who’d detailed the American government’s disastrous attempt to transfer East Coast eels to California during the nineteenth century.

The scrolling burned through another fifteen minutes. Callie checked Dr. Jerry’s schedule. He had four more patients this afternoon. She went to the kitchen and made him a sandwich, sprinkling a generous supply of animal crackers on the side.

Callie knocked on Dr. Jerry’s door before entering. He was laid out on the couch, mouth hanging open. His glasses were askew. A book was flattened on his chest. The Complete Sonnets of William Shakespeare. A gift from his late wife.

“Dr. Jerry?” She squeezed his foot.

As always, he was a bit startled and disoriented to find Callie hovering over him. It was like Groundhog Day, except everybody knew that groundhogs were vicious murderers.

He adjusted his glasses so he could see his watch. “That went by fast.”

“I made you lunch.”

“Wonderful.”

He groaned as he got off the couch. Callie gave him a little help when he started to fall back.

She asked, “How was your executive time?”

“Very good, but I had a strange dream about anglerfish. Have you ever met one?”

“Not to my recollection.”

“I’m glad to hear that. They live in the darkest, loneliest places, which is a very good thing because they are not the most attractive specimens.” He cupped his hand to his mouth as if to convey a confidence. “Especially the ladies.”

Callie sat on the edge of his desk. “Tell me.”

“The male spends all his life sniffing out a female. As I said, it’s very dark where they live, so nature gave him olfactory cells that are attracted to the female’s pheromones.” He held up his hand to stop the story. “Did I mention she has a long, illuminated filament on her head that sticks out like a flashlight finger?”

“No.”

“Bioluminescence.” Dr. Jerry looked delighted by the word. “So, once our Romeo finds his Juliet, he bites onto her just below the tail.”

Callie watched as he illustrated with his hands, fingers clomping down on his fist.

“Then, the male releases enzymes that dissolve both his mouth and her skin, which effectively fuses them together. Then — this is the miraculous part — his eyes and internal organs dissolve until he’s just a reproductive sac melded onto her for the rest of his miserable existence.”

Callie laughed. “Damn, Dr. Jerry. That sounds exactly like my first boyfriend.”

He laughed, too. “I don’t know why I thought about that.

Funny how the noggin’ works.”

Callie could’ve spent the rest of her life worrying that Dr. Jerry was using the anglerfish as a metaphor for how she treated him, but Dr. Jerry wasn’t a metaphor guy. He just really loved talking about fish.

She helped him slip into his lab coat.

He asked, “Did I ever tell you about the time I got a house call on a baby bull shark in a twenty-gallon aquarium?”

“Oh, no.”

“They’re called pups, by the way, though that doesn’t have the same joie de vivre as baby shark. Naturally, the owner was a dentist. Poor simpleton had no idea what he was dealing with.” Callie followed him down the hall, listening to him explain the meaning of viviparous. She steered him into the kitchen where she made sure he cleaned his plate. Cracker crumbs speckled the table as he told her another story about another fish, then moved on to marmosets. Callie had realized long ago that Dr. Jerry was using her more as paid companionship. Considering what other men had paid Callie for, she was grateful for the change in scenery. The four remaining appointments made the rest of the day go by fast. Dr. Jerry loved annual check-ups because there was seldom anything seriously wrong. Callie scheduled follow-up visits, teeth cleanings, and, because Dr. Jerry thought it impolite to bring up a lady’s weight, lectured a rotund dachshund’s owners about food restrictions. At the end of the day, Dr. Jerry tried to pay her, but Callie reminded him that she didn’t get paid again until the end of next week.

She had looked up signs of dementia on her phone. If that was what Dr. Jerry was staring down, then she figured he was still okay to work. He might not know what day it was, but he could calculate fluids with electrolytes and additives like potassium or magnesium without writing down the numbers, which was better than most people could claim.

Callie scrolled through Twitter as she walked to the MARTA bus stop. The eel historian had gone silent and the Kiwi zoo keeper was asleep tomorrow, so she went to Facebook.

Drug-seeking canines were not Callie’s only creation. Since 2008, she’d been lurking on the assholes she’d gone to high school with. Her profile photo showed a blue Siamese fighting fish who went by the name Swim Shady.

Her eyes glazed over as she read the latest shitposting from Lake Point’s illustrious class of 2002. Complaints about schools closing, wild deep-state conspiracies, disbelief in the virus, belief in the virus, pro-vaccine rants, anti-vaccine rants, and the usual racism, sexism and anti-Semitism that plagued social media. Callie would never understand how Bill Gates had been shortsighted enough to give everybody easy access to the internet so that some day, these jackasses could reveal all of his dastardly plans.

She dropped her phone back into her pocket as she sat on the bench at the bus stop. The dirty Plexiglas enclosure was striped with graffiti. Trash rounded off the corners. Dr. Jerry’s clinic was in an okay area, but that was a subjective observation. His strip-mall neighbors were a porn shop that was forced to close during the pandemic and a barbershop Callie was pretty sure had only stayed open because it served as a gambling front. Every time she saw a wild-eyed loser stumbling out the back door, she said a small prayer of thanks that gambling was not one of her addictions.

A garbage truck sputtered black exhaust and rot as it slowly rocked past the bus stop. One of the guys hanging off the back gave Callie a wave. She waved back because it was the polite thing to do. Then his buddy started waving and she turned her head away.

Her neck rewarded her for the too-quick turn, tightening the muscles like a clamp. Callie reached up, fingers finding the long scar that zippered down from the base of her skull. C1 and C2 were the cervical vertebrae that allowed for one-half of the head’s forward, back, and rotational movements. Callie had two two-inch titanium rods, four screws and a pin that formed a cage around the area. Technically, the surgery was called a cervical laminectomy, but more commonly it was known as a fusion, because that was the end result: the vertebrae fused together into one bony clump.

Even though two decades had passed since the fusion, the nerve pain could be sudden and debilitating. Her left arm and hand could go completely numb without warning. She had lost nearly half the mobility in her neck. Nodding and shaking her head were do-able, but limited. When she tied her shoes, she had to bring her foot to her hands rather than the other way around. She hadn’t been able to look over her shoulder since the surgery, a devastating loss because Callie could never be the heroine pictured on the cover of a Victorian mystery.

She tilted back against the Plexiglas so she could look up at the sky. The waning sun warmed her face. The air was cool and crisp. Cars rolled by. Children were laughing on a nearby playground. The steady beat of her own heart gently pulsed in her ears.

The women she’d gone to high school with were currently driving their kids to football practice or piano lessons. They were watching their sons do homework, holding their breath while their daughters practiced cheerleading routines in the backyard. They were leading meetings, paying bills, going to work and living normal lives where they didn’t steal drugs from a kindly old man. They weren’t shaking inside of their bones because their body was crying out for a drug that they knew would eventually kill them.

At least a lot of them had gotten fat.

Callie heard the hiss of air brakes. She turned to look for the bus. She did it correctly this time, angling her shoulders along with her head. Despite the accommodation, pain shot fire up her arm and into her neck.

“Shit.”

Not her bus, but she’d paid the price for looking. Her breath stuttered. She pushed back against the Plexiglas, hissed air between clenched teeth. Her left arm and hand were numb, but her neck pulsed like a pus-filled sac. She concentrated on the daggers flaying her muscles and nerves. Pain could be its own addiction. Callie had lived with it for so long that when she thought of her life before, she only saw tiny bursts of light, stars barely penetrating the darkness.

She knew that there had been a time long ago when all she’d craved was the rush of endorphins that came from running hard or riding her bike too fast or flipping herself diagonally across the gym floor. In cheerleading, she had flown — soared — into the air, doing a hip-over-head rotation, or a back tuck, a front flip, a leg kick, arabesque, the needle, the scorpion, the heel stretch, the bow-and-arrow, a landing spin that was so dizzying all she could do was wait for four sets of strong arms to basket her fall.

Until they didn’t.

A lump came into her throat. Her hand reached up again, this time finding one of the four bony bumps that circled her head like points on a compass. The surgeon had drilled pins into her skull to hold the halo ring in place while her neck healed. Callie had worried the spot above her ear so much it felt callused.

She wiped tears from the corners of her eyes. She dropped her hand into her lap. She massaged the fingers, trying to press some feeling back into the tips.

Seldom did she let herself think about what she’d lost. As her mother said, the tragedy of Callie’s existence was that she was smart enough to know how stupid she’d been. This weighty knowledge wasn’t limited to Callie. In her experience, most junkies understood addiction as well as, if not better than, a lot of doctors. For instance, Callie knew that her brain, like every other brain, had something called mu opioid receptors. The receptors were also scattered along her spine and other places, but, for the most part, they hung out in the brain. The easiest way to describe a mu receptor’s job was to say that they controlled feelings of pain and reward.

The first sixteen years of her life, Callie’s receptors had functioned at a reasonable level. She’d sprain her back or twist her ankle and an endorphin rush would spread through her blood and latch onto the mu receptors, which in turn would dampen the pain. But only temporarily and not by nearly enough. In elementary school, she’d used NSAIDs like Advil or Motrin to replace the endorphins. Which had worked. Until they didn’t.

Thanks to Buddy, she’d been introduced to alcohol, but the thing about alcohol was, even in Lake Point, not many stores would sell a handle of tequila to a child, and Buddy had for obvious reasons been unable to supply her past the age of fourteen. And then Callie had broken her neck at sixteen and, before she knew it, she was on her way to a lifelong love affair with opioids.

Narcotics could blow an endorphin rush out of the water, and they were laughably better than NSAIDs and alcohol, except once they latched onto the mu receptors, they didn’t like to let go. Your body responded by making more mu receptors, but then your brain remembered how great it was to have full mu receptors and told you to fill them back up again. You could watch TV or read a book or try to contemplate the meaning of life, but your mus would always be there tapping their tiny mu feet, waiting for you to feed them. This was called craving.

Unless you were wired like a magical fairy or had Houdini-level self-control, you would eventually feed that craving. And eventually, you would need stronger and stronger narcotics just to keep all those new mus happy, which was incidentally the science behind tolerance. More narcotics. More mus. More narcotics. And so on.

The worst part was when you stopped feeding the mus, because they gave you around twelve hours before they took your body hostage. Their ransom demand was conveyed through the only language they understood, which was debilitating pain. This was called withdrawal, and there were autopsy photos that were more pleasant to look at than a junkie going through opioid withdrawal. So, Callie’s mother was absolutely right in that Callie knew exactly when she’d taken her first step down the road to a lifetime of stupidity. It wasn’t when she’d slammed headfirst onto the gymnasium floor, cracking two vertebrae in her neck. It was the first time her script for Oxy had run out and she’d asked a stoner in English class if he knew how she could get more.

A tragedy in one act.

Callie’s MARTA bus harrumphed to the stop, beaching itself on the curb.

She groaned worse than Dr. Jerry when she stood up. Bad knee. Bad back. Bad neck. Bad girl. The bus was half-full, some people wearing masks, some figuring their lives were shitty enough so why postpone the inevitable. Callie found a seat in the front with all the other creaky old women. They were housecleaners and waitresses with grandchildren to support, and they gave Callie the same wary look they’d give a family member who had stolen their checkbook one too many times. To save them all the embarrassment, she stared out the window as gas stations and auto parts stores gave way to strip clubs and check-cashing joints.

When the scenery got too bleak, her phone came out. She started doomscrolling Facebook again. There was no logic to her quest to keep up with these nearly middle-aged twits. Most of them had stayed in the Lake Point area. A few had done well, but well for Lake Point, not well for a normal human being. None of them had been Callie’s friends in school. She had been the least popular cheerleader in the history of cheerleaders. Even the weirdos at the freak table hadn’t welcomed her into the fold. If any of them remembered her at all, it was as the girl who’d shit herself in front of an entire school assembly. Callie could still remember the sensation of numbness spreading down her arms and legs, the disgusting stench of her bowels releasing as she collapsed onto the hard wooden floor of the gymnasium.

All for a sport that had about as much prestige as an egg-rolling contest.

The bus shivered like a whippet as it neared her stop. Callie’s knee locked out when she tried to stand. She had to hit it with her fist to get going. As she limped down the stairs, she considered all the drugs in her backpack. Tramadol, methadone, ketamine, buprenorphine. Mix them all into a pint of tequila and she could get a front-row seat to Kurt Cobain and Amy Winehouse talking about what a douche Jim Morrison could be.

“Hey Cal!” Crackhead Sammy waved frantically from his perch in a broken lawn chair. “Cal! Cal! Come here!”

Callie walked across a vacant lot to Sammy’s nesting area — the chair, a leaky tent and a bunch of cardboard that didn’t seem to serve a purpose. “What’s going on?”

“So, your cat, all right?” Callie nodded.

“There was a pigeon, and he just —” Sammy did a crazy swooping gesture with his arms. “He caught that damn rat-bird in the air and ate it right in front of me. It was fucked up, man. He sat there chewing on pigeon head for half an hour.”

Callie grinned proudly as she dug around in her backpack. “Did he share?”

“Hell no, he just looked at me. He looked at me, Callie. And he had this look, like, like I don’t know. Like he wanted to tell me something.” Sammy guffawed. “Ha! Like, ‘Don’t smoke crack.’”

“I’m sorry. Cats can be very judgmental.” She found the sandwich she’d made for her dinner. “Eat this before you hit it tonight.”

“Right, right.” Sammy tucked the sandwich under a strip of cardboard. “Listen, though, do you think he was trying to tell me something?”

“I’m not sure,” Callie said. “As you know, cats choose not to talk because they’re afraid we’ll make them pay taxes.”

“Ha!” Sammy jabbed a finger at her. “Snitches get stitches! Oh-oh-hey Cal, wait up a sec, okay? I think Trap is looking for you so —”

“Eat your sandwich.” Callie walked away, because Sammy could rattle on for the rest of the night. And that was without the crack.

Callie rounded the corner, taking a labored breath. Trap looking for her was not a good development. He was a fifteen-year-old meth freak who’d graduated early with a degree in dipshittery. Fortunately, he was terrified of his mother. As long as Wilma got her patronage, her idiot son stayed on a tight leash.

Still, Callie swung her backpack around to the front of her chest as she got closer to the motel. The walk was not completely unpleasant because it was familiar. She passed by empty lots and abandoned houses. Graffiti scarred a crumbling brick retaining wall. Used syringes were scattered across the sidewalk. By habit, her eye searched for usable needles. She had her dope kit in her backpack, a plastic Snoopy watch case with her tie-off, a bent spoon, an empty syringe, some cotton, and a Zippo lighter.

What she enjoyed most about shooting heroin was the pageantry of the act. The flick of the lighter. The vinegar smell as it cooked on the spoon. Drawing up the dirty brown liquid into the syringe.

Callie shook her head. Dangerous thoughts.

She followed the dirt-packed strip that traced around the backyards of a residential street. The energy abruptly changed. Families lived here. Windows were thrown open. Music played loudly. Women yelled at their boyfriends. Boyfriends yelled at their women. Children ran around a sputtering sprinkler. It was just like the rich parts of Atlanta, but louder and more cramped and less pale.

Through the trees, Callie spotted two squad cars parked at the far end of the road. They weren’t scooping up people. They were waiting for the sun to go down and the calls to come in — Narcan for this junkie, the emergency room for another, a long wait on the coroner’s van, child services, probation officers, and Veterans Affairs — and that was just for a Monday night. A lot of people had turned to illicit comforts during the pandemic. Jobs were lost. Food was scarce. Kids were starving. The number of overdoses and suicides had gone through the roof. All the politicians who had expressed deep concern about mental health during the lockdowns had shockingly been unwilling to spend money on helping the people who were losing their minds.

Callie watched a squirrel skitter around a telephone pole. She angled her route toward the back of the motel. The two-story concrete block building was behind a row of scraggly bushes. She pushed aside the limbs and stepped onto the cracked asphalt. The Dumpster gave off a pungent welcome. She scanned the area, making sure Trap didn’t sneak up on her.

Her mind wandered back to the lethal cornucopia of drugs in her backpack. Meeting Kurt Cobain would be amazing, but her desire for self-harm had passed. Or at least had simmered down to her usual quest for self-harm, the kind that didn’t end in certain death, only possible death, and then maybe she could be brought back so why not bump it up a little more, right? The police would come in time, right?

What Callie wanted tonight was to take a long shower and curl up in bed with her pigeon-snacking cat. She had enough methadone to get her through the night and out of bed in the morning. She could sell on the way to work. Dr. Jerry would have a heart attack if she showed up before noon anyway.

Callie was smiling when she turned the corner because she seldom had an actual plan.

“’Sup girl?” Trap was leaning against the wall smoking a joint. He gave her the once-over, and she reminded herself that he was a teenager with the brain of a five-year-old and a grown man’s potential for violence. “Got somebody looking for you.”

Callie felt the hairs go up on her neck. She had spent the majority of her adult life making sure that no one ever looked for her. “Who?”

“White dude. Nice car.” He shrugged, like that was enough of a description. “Whatchu got in that backpack?”

“None of your fucking business.” Callie tried to walk past him, but he grabbed her arm.

“Come on,” Trap said. “Mama told me to collect.”

Callie laughed. His mother would kick his balls into his throat if he took a cut off her piece. “Let’s go find Wilma right now and make sure that’s true.”

Trap’s eyes got shifty. At least that’s what she thought. Too late, Callie realized he was signaling someone behind her. She started to turn her body because she could not turn her head.

A man’s muscular arm looped around her neck. The pain was instantaneous, like lightning striking down from the sky. Callie’s hips jutted forward. She fell back against the man’s chest, her body levering like the hinge on a door.

His breath was hot in her ear. “Don’t move.”

She recognized Diego’s shrill voice. He was Trap’s fellow meth freak. They’d smoked so much crystal that their teeth were already falling out. Either one of them alone was a nuisance. Together, they were a breaking news rape-and-murder story waiting to happen.

“Whatchu got, bitch?” Diego yanked harder on her neck. His free hand slipped under the backpack and found her breast. “You got these little titties for me, girl?”

Callie’s left arm had gone completely numb. She felt like her skull was going to break off at the root. Her eyes closed. If she was going to die, let it be before her spine snapped.

“Let’s see what we got.” Trap was close enough for her to smell the rotten teeth in his mouth. He unzipped the backpack. “Damn, bitch, you been holdin’ out on —”

They all heard the distinctive click-clack of a slide being pulled on a nine-millimeter handgun.

Callie couldn’t open her eyes. She could only wait for the bullet. Trap said, “Who the fuck are you?”

“I’m the motherfucker who’s gonna put another hole in your head if you assholes don’t step the fuck off right now.”

Callie opened her eyes. “Hey, Harleigh.”

5

“Christ, Callie.”

She watched Leigh angrily dump the backpack onto the bed. Syringes, tablets, vials, tampons, jellybeans, pens, notebook, two library books on owls, Callie’s dope kit. Instead of railing against the stash, her sister’s gaze bounced around the dingy motel room as if she expected to find secret stashes of opium inside the painted concrete block walls.

Leigh asked, “What if I’d been a cop? You know you can’t carry this much weight.”

Callie leaned against the wall. She was used to seeing different versions of Leigh — her sister had more aliases than a cat — but the side of Leigh that could pull a gun on a couple of junkie teenagers hadn’t reared its head in twenty-three years.

Trap and Diego had better thank their fucking stars that she was carrying a Glock instead of a roll of plastic film.

Leigh warned, “Trafficking would put you in prison for the rest of your life.”

Callie stared longingly at her dope kit. “I hear it’s easier for bottoms inside.”

Leigh swung around, hands on her hips. She was wearing high heels and one of her expensive ladybitch suits, which made her presence in this shithole motel somewhat comical. And that included the loaded gun sticking out of the waistband of her skirt.

Callie asked, “Where’s your purse?”

“Locked in the trunk of my car.”

Callie was going to tell her that was a stupid rich white lady thing to do, but her skull was still throbbing from when Diego had nearly cracked the remaining vertebrae in her neck. “It’s good to see you, Har.”

Leigh stepped closer, looking into Callie’s eyes to check her pupils. “How stoned are you?”

Not enough was Callie’s first thought, but she didn’t want to run Leigh off so soon. The last time she’d seen her sister, Callie was coming off spending two weeks on a ventilator in Grady Hospital’s ICU.

Leigh said, “I need you straight right now.”

“Then you’d better hurry.”

Leigh crossed her arms over her chest. She clearly had something to say, but she just as clearly wasn’t ready yet. She asked, “Have you been eating? You’re too thin.”

“A woman can never be —”

“Cal.” Leigh’s concern cut like a shovel through bullshit. “Are you okay?”

“How’s your anglerfish?” Callie enjoyed the confusion on her sister’s face. There was a reason the weirdos hadn’t wanted the least popular cheerleader at the freak table. “Walter. How’s he doing?”

“He’s okay.” The hardness left Leigh’s expression. Her hands dropped down to her sides. There were only three people alive who ever got to see her guard down. Leigh brought up the third without prompting. “Maddy’s still living with him so she can go to school.”

Callie tried to rub the feeling back into her arm. “I know that’s hard for you.”

“Well, yeah, everything’s hard for everybody.” Leigh started pacing around the room. It was like watching a cymbal-clanging monkey wind itself up. “The school just sent out an email that some stupid mother threw a superspreader party last weekend. Six kids have tested positive so far. The entire class is on virtual learning for two weeks.”

Callie laughed, but not over the stupid mother. The world Leigh lived in was like Mars compared to her own.

Leigh nodded at the window. “Is that for you?”

Callie smiled at the muscular black cat on the ledge. Binx stretched his back as he waited for entry. “He caught a pigeon today.”

Leigh clearly didn’t give a shit about the pigeon, but she tried, “What’s his name?”

“Fucking Bitch.” Callie grinned at her sister’s startled reaction. “I call him Fitch for short.”

“Isn’t that a girl’s name?”

“He’s gender fluid.”

Leigh pressed together her lips. This wasn’t a social visit. When Harleigh socialized, she went to fancy dinner parties with other lawyers and doctors and the Dormouse fast asleep between the Hatter and March Hare.

She only sought out Callie when something really bad had happened. A pending warrant. A visit at the county jail. A looming court case. A Covid diagnosis where the only expendable person who could nurse her back to health was her baby sister.

Callie ran through her most recent transgressions. Maybe that stupid jaywalking ticket had put her in the shit. Or maybe Leigh had gotten a tip-off from one of her connections that Dr. Jerry was being looked at by the DEA. Or, more likely, one of the morons Callie was selling to had flipped to keep his own sorry ass out of jail.

Fucking junkies.

She asked, “Who’s after me?”

Leigh circled her finger in the air. The walls were thin. Anyone could be listening.

Callie hugged Binx close. They had both known that one day, Callie would get herself into the kind of trouble that her big sister wouldn’t be able to get her out of.

“Come on,” Leigh said. “Let’s go.”

She didn’t mean take a stroll around the block. She meant pack up your shit, stick that cat in something, and get in the car.

Callie looked for clothes while Leigh repacked the backpack. She would miss her bedspread and her flowery blanket, but this wasn’t the first time she’d abandoned a place. Normally sheriff’s deputies were standing outside with an eviction notice. She needed underwear, lots of socks, two clean T-shirts, and a pair of jeans. She had one pair of shoes and they were on her feet. More T-shirts could be found at the thrift store. Blankets would be handed out at the shelter, but she couldn’t stay there because they didn’t allow pets. Callie stripped off a pillowcase to hold her meager stash, then loaded in Binx’s food, his pink mouse toy, and a cheap plastic Hawaiian lei the cat liked to drag around when he was having feelings.

“Ready?” Leigh had the backpack over her shoulder. She was a lawyer, so Callie didn’t explain what a gun and a shit ton of drugs could mean because her sister had earned herself a slot in that rarefied world where the rules were negotiable.

“Just a minute.” Callie used her foot to kick Binx’s carrier out from under the bed. The cat stiffened, but didn’t fight when Callie placed him inside. This wasn’t his first eviction, either.

She told her sister, “Ready.”

Leigh let Callie go first out the door. Binx started hissing when he was put into the back seat of the car. Callie buckled the seatbelt around his carrier, then got into the front seat and did the same for herself. She watched her sister carefully. Leigh was always in control, but even the way she turned the key in the ignition was done with a strangely precise flick of her wrist. Everything about her was freaked out, which was worrying, because Leigh never freaked out.

Trafficking.

Junkies were by necessity part-time lawyers. Georgia had mandatory sentencing based on weight. Twenty-eight or more grams of cocaine: ten years. Twenty-eight or more grams of opiates: twenty-five years. Anything over four hundred grams of methamphetamines: twenty-five years.

Callie tried to do the math, to divide her list of customers who had probably flipped by the ounces or total grams she had sold in the last few months, but, no matter how she toggled it around, the numerator kept bringing her back to fucked.

Leigh turned right out of the motel parking lot. Nothing was said as they pulled onto the main road. They passed the two cop cars at the end of the residential street. The cops barely gave the Audi a glance. They likely assumed the two women were looking for a stoned kid or slumming around trying to score for themselves.

They both kept silent as Leigh pulled out onto the outer loop, past Callie’s bus stop. The fancy car smoothly navigated the bumpy asphalt. Callie was used to the jerks and bounces of public transportation. She tried to remember the last time she’d ridden in a car. Probably when Leigh had driven her home from Grady Hospital. Callie was supposed to convalesce at Leigh’s zillion-dollar condo, but Callie had been on the street with a needle in her arm before the sun had come up.

She massaged her tingling fingers. Some of the feeling was coming back, which was good but also like needles scraping into her nerves. She studied her sister’s sharp profile. There was something to be said for having enough money to age well. A gym in her building. A doctor on call. A retirement account. Nice vacations. Weekends off. As far as Callie was concerned, her sister deserved every luxury she could give herself. Leigh hadn’t just fallen into this life. She had clawed her way up the ladder, studying harder, working harder, making sacrifice after sacrifice to give herself and Maddy the best life possible.

If Callie’s tragedy was self-knowledge, Leigh’s was that she would never, ever let herself accept that her good life wasn’t somehow linked to the unmitigated misery of Callie’s.

“Are you hungry?” Leigh asked. “You need to eat.”

There wasn’t even a polite pause for Callie’s response. They were in big sister/little sister mode. Leigh pulled into a McDonald’s. She didn’t consult Callie as she ordered at the drive-thru, though Callie assumed the Filet-O-Fish was for Binx. Nothing was said as the car inched toward the window. Leigh found a mask in the console between the seats. She exchanged cash for bags of food and drinks, then passed it all to Callie. She took off her mask. She kept driving.

Callie didn’t know what to do but get everything ready. She wrapped a Big Mac in a napkin and handed it to her sister. She picked at a double cheeseburger for herself. Binx had to settle for two French fries. He would’ve loved the fish sandwich, but Callie wasn’t sure she could clean cat diarrhea out of the contrast stitching in her sister’s fancy leather seats.

She asked Leigh, “Fries?”

Leigh shook her head. “You have them. You’re too skinny, Cal. You need to back off the dope for a while.”

Callie took a moment to appreciate the fact that Leigh had tens of thousands of dollars of Leigh’s money wasted on rehab and countless angst-filled conversations, but both of their lives had become a hell of a lot easier since Leigh had entered into acceptance.

“Eat,” Leigh ordered.

Callie looked down at the hamburger in her lap. Her stomach turned. There wasn’t a way to tell Leigh that it wasn’t the dope that was making her lose weight. She had never gotten her appetite back after Covid. Most days, she had to force herself to eat. Telling that to Leigh would only end up burdening her sister with more guilt that she did not deserve to carry.

“Callie?” Leigh shot her an annoyed look. “Are you going to eat or do I have to force-feed you?”

Callie choked down the rest of the fries. She made herself finish exactly half of the hamburger. She was downing the Coke when the car finally rolled to a stop.

She looked around. Instantly, her stomach started searching for all sorts of ways to get rid of the food. They were smack in the residential part of Lake Point, the same place Leigh used to bring them in her car when they needed to get away from their mother. Callie had avoided this hellhole for two decades. She took the long bus from Dr. Jerry’s just so she didn’t have to see the depressing, squat houses with their narrow carports and sad front yards.

Leigh left the car running so the air could stay on. She turned toward Callie, leaning her back against the door. “Trevor and Linda Waleski came to my office last night.”

Callie shivered. She kept what Leigh had told her at a distance, but there was a faint darkness on the horizon, an angry gorilla pacing back and forth across her memories — short-waisted, hands always fisted, arms so muscled that they wouldn’t go flat to his sides. Everything about the creature screamed ruthless motherfucker. People turned in the opposite direction when they saw him in the street.

Get on the couch, little dolly. I’m so hot for you I can’t stand it.

Callie asked, “How’s Linda?”

“Rich as shit.”

Callie looked out the window. Her vision blurred. She could see the gorilla turning, glaring at her. “I guess they didn’t need Buddy’s money after all.”

“Callie.” Leigh’s tone was filled with urgency. “I’m sorry, but I need you to listen.”

“I’m listening.”

Leigh had good reason not to believe her, but she said, “Trevor goes by Andrew now. They changed their last name to Tenant after Buddy — after he disappeared.”

Callie watched the gorilla start running toward her. Spit sprayed from his mouth. His nostrils flared. His thick arms rose up. He lunged at her, teeth bared. She smelled cheap cigars and whiskey and her own sex.

“Callie.” Leigh grabbed her hand, holding so tight that the bones shifted. “Callie, you’re okay.”

Callie closed her eyes. The gorilla stalked back to its place on the horizon. She smacked her lips. She had never wanted heroin so much as she did in this moment.

“Hey.” Leigh squeezed her hand even tighter. “He can’t hurt you.”

Callie nodded. Her throat felt sore, and she tried to remember how many weeks, maybe as long as a few months, it had taken before she could swallow without pain after Buddy had tried to choke the life out of her.

You worthless piece of shit, her mother had said the day after. I didn’t raise you to let some stupid punk bitch kick your ass on the playground.

“Here.” Leigh let go of her hand. She reached into the back seat to open the carrier. She scooped up Binx and placed him in Callie’s lap. “Do you want me to stop talking?”

Callie held Binx close. He purred, pushing his head against the base of her chin. The weight of the animal brought her comfort. She wanted Leigh to stop, but she knew that hiding from the truth would only shift all of the burden onto her sister.

She asked, “Does Trevor look like him?”

“He looks like Linda.” Leigh went silent, waiting for another question. This wasn’t a legal tactic she’d learned in the courtroom. Leigh had always been a trickle-truther, slowly feeding back alley.

Callie pressed her lips to the top of Binx’s head, the same way she used to do with Trevor. “How did they find you?”

“Remember that article in the paper?”

“The urinator,” Callie said. She had been so proud to see her big sister profiled. “Why does he need a lawyer?”

“Because he’s been accused of raping a woman. Several women.”

The information was not as surprising as it should’ve been. Callie had spent so much time watching Trevor test the waters, seeing how far he could push things, exactly the way his father always had. “So, he’s like Buddy after all.”

“I think he knows what we did, Cal.”

The news hit her like a hammer. She felt her mouth open, but there were no words. Binx grew irritated by the sudden lack of attention. He jumped onto the dashboard and looked out the windshield.

Leigh said it again, “Andrew knows what we did to his father.”

Callie felt the cold air from the vents seep into her lungs. There was no hiding from this conversation. She couldn’t turn her head, so she turned her body, pressing her back against the door the same way that Leigh had. “Trevor was asleep. We both checked.”

“I know.”

“Huh,” Callie said, which was what she said when she didn’t know what else to say.

“Cal, you don’t have to be here,” Leigh said. “I can take you to —”

“No.” Callie hated being placated, though she knew that she needed it. “Please, Harleigh. Tell me what happened. Don’t leave anything out. I have to know.”

Leigh was still visibly reluctant. The fact that she didn’t protest again, that she didn’t tell Callie to forget about it, that Leigh was going to handle everything like she always did, was terrifying.

She started at the beginning, which was around this time last night. The meeting at her boss’s office. The revelation that Andrew and Linda Tenant were ghosts from her past. Leigh went into detail about Trevor’s girlfriend, Reggie Paltz the private detective who was a little too close, the lies about Callie’s life in Iowa. She explained the rape charges against Andrew, the possible other victims. When she got to the detail about the knife slicing just above the femoral artery, Callie felt her lips part.

“Hold on,” she said. “Back up. What did Trevor say exactly?”

“Andrew,” Leigh corrected. “He’s not Trevor anymore, Callie. And it’s not what he said, it’s how he said it. He knows that his father was murdered. He knows that we got away with it.”

“But —” Callie tried to wrap her brain around what Leigh was saying. “Trev — Andrew is using a knife to hurt his victims the same way I killed Buddy?”

“You didn’t kill him.”

“Fuck, Leigh, sure.” They weren’t going to have that stupid argument again. “You killed him after I killed him. It’s not a contest. We both murdered him. We both chopped him up.”

Leigh fell back into silence. She was giving Callie space, but Callie didn’t need space.

“Harleigh,” she said. “If the body was found, it’s too late to know how he died. Everything would be gone by now. They’d just find bones. And not even all of them. Just scattered pieces.”

Leigh nodded. She had already thought about this.

Callie went through the other options. “We looked for more cameras and cassettes and — everything. We cleaned the knife and put it back in the drawer. I babysat Trevor for another whole damn month before they finally left town. I used that steak knife every time I could. There’s no way anybody could link it back to what we did.”

“I can’t tell you how Andrew knows about the knife, or the cut to Buddy’s leg. All I can say is that he knows.”

Callie forced her mind to go back to that night, though by necessity she had worked to forget most of it. She flipped through the events quickly, not pausing on any one page. Everybody thought that history was like a book with a beginning, a middle, and an end. That’s not how it worked. Real life was all middle.

She told Leigh, “We turned that house upside down.”

“I know.”

“How does he...” Callie flipped back through it again, this time more slowly. “You waited six days before you left for Chicago. Did we talk about it in front of him? Did we say something?”

Leigh shook her head. “I don’t think we did, but...”

Callie didn’t need her to say the words. They had both been in shock. They had both been teenagers. Neither of them was a criminal genius. Their mother had figured out that something bad had happened, but all she’d told them was Don’t put me in the middle of whatever shit you’re tangled up in because I will throw both of your sorry asses under the first bus that swings by.

Leigh said, “I don’t know what mistake we made but, obviously, we made a mistake.”

Callie could tell by looking at her sister that whatever this mistake was, Leigh was piling it onto the other pile of guilt that already weighed her down. “What did Andrew say exactly?”

Leigh shook her head, but her recall had always been excellent. “He asked me if I would know how to commit a crime that would destroy somebody’s life. He asked if I’d know how to get away with cold-blooded murder.”

Callie bit her bottom lip.

“And then he said today isn’t like when we were kids. Because of cameras.”

“Cameras?” Callie echoed. “He said cameras specifically?”

“He said it half a dozen times — that cameras are everywhere, on doorbells, houses, traffic cameras. You can’t go anywhere without being recorded.”

“We didn’t search Andrew’s room,” Callie said. That was the only place they hadn’t considered. Buddy barely spoke to his son. He wanted nothing to do with him. “Andrew was always stealing things. Maybe there was another cassette?”

Leigh nodded. She had already considered the possibility.

Callie felt her cheeks burn bright red. Andrew was ten when it happened. Had he found a cassette? Had he watched his father screwing Callie every which way he could think of? Was that why he was still obsessed with her?

Was that why he was raping women?

“Harleigh, logic that out. If Andrew has a video, then all it shows is that his father was a pedophile. He wouldn’t want that out in the open.” Callie fought off a shudder. She didn’t want that out in the open either. “Do you think Linda knows?”

“No.” Leigh shook her head, but there was no way she could be sure.

Callie put her hands to her burning cheeks. If Linda knew, then that would be the end of her. She had always loved the woman, almost worshipped her for her steadiness and honesty. As a kid, it had never occurred to Callie that she was cheating with Linda’s husband. In her screwed-up head, she had seen them both as surrogate parents.

She asked her sister, “Before he started talking about cameras, did Andrew ask you about anything from that night, or around Buddy’s disappearance?”

“No,” Leigh answered. “And like you said, even if Andrew had a cassette, it wouldn’t show how Buddy died. How does he know about the knife? The leg wound?”

Callie watched Binx grooming his paw. She was absolutely clueless.

Until she wasn’t.

She told Leigh, “I looked into — I looked up stuff in one of Linda’s anatomy textbooks after it happened. I wanted to know how it worked. Andrew could’ve seen that.”

Leigh seemed skeptical, but she said, “It’s possible.”

Callie pressed her fingers to her eyes. Her neck pulsed with pain. Her hand was still tingling. The gorilla was restless in the distance.

Leigh asked, “How often did you look it up?”

Callie saw a projection on the back of her eyelids: the textbook open on the Waleskis’ kitchen table. The diagram of a human body. Callie had traced her finger along the femoral artery so many times that the red line had faded into pink. Had Andrew noticed? Had he seen Callie’s obsessive behavior and put it all together?

Or was there a heated conversation between Callie and Leigh that he’d overheard? They had argued constantly about what to do after Buddy — whether their plan was working, what stories they had told to cops and social workers, what to do with the money. Andrew could’ve been hiding, listening, taking notes. He had always been a sneaky little shit, jumping out from behind things to scare Callie, stealing her pens and books, terrorizing the fish in the aquarium.

Any of these scenarios was possible. Any one would elicit the same response from Leigh: It’s my fault. It’s all my fault.

“Cal?”

She opened her eyes. She only had one question. “Why is this getting to you, Leigh? Andrew doesn’t have any proof or he’d be at a police station.”

“He’s a sadistic rapist. He’s playing a game.”

“So fucking what? Jesus, Leigh. Sac up.” Callie opened her arms in a shrug. This was how it worked. Only one of them could fall apart at a time. “You can’t play a game with somebody if they’re not willing to suit up. Why are you letting that little freak get into your head? He doesn’t have jack shit.”

Leigh didn’t answer, but she was obviously still rattled. Tears had filled her eyes. Her color was off. Callie noticed a speck of dried vomit on the neck of her shirt. Leigh had never had a strong stomach. That was the problem with having a good life. You didn’t want to lose it.

Callie said, “Lookit, what do you always tell me? Stick to the damn story. Buddy came home. He was freaked out about a death threat. He didn’t say who had made it. I called you. You picked me up. He was alive when we left. Mom pounded the hell out of me. That’s it.”

“D-FaCS,” Leigh said, using the abbreviation for the Department of Family and Children’s Services. “When the social worker came to the house, did she take any photos?”

“She barely took a report.” Callie honestly couldn’t remember, but she knew how the system worked and so did her sister. “Harleigh, use your brain. We weren’t living in Beverly Hills, 90210. I was just another kid whose drunk mother kicked the shit out of her.”

“The social worker’s report could be somewhere, though. The government never throws anything away.”

“I doubt the bitch even filed it,” Callie said. “All of the social workers were terrified of Mom. When the cops questioned me about Buddy disappearing, they didn’t say a damn thing about how I looked. They didn’t ask you about it, either. Linda gave me antibiotics and set my nose, but she never asked one single question. Nobody pushed it with social services. Nobody at school said a damn thing.”

“Yeah, well, that asshole Dr. Patterson wasn’t exactly a child advocate.”

The humiliation flooded back like a tidal wave pounding Callie down onto the shore. No matter how much time had passed, she could not move past not knowing how many men had seen the things she’d done with Buddy.

Leigh said, “I’m sorry, Cal. I shouldn’t have said that.”

Callie watched Leigh search for a tissue in her purse. She could remember a time when her big sister had concocted murderous plots and grand conspiracies against the men who had watched Callie being defiled. Leigh had been willing to throw her life away in order to get revenge. The only thing that had pulled her back from the brink was the fear of losing Maddy. Callie told Leigh what she always told Leigh, “It’s not your fault.”

“I should’ve never left for Chicago. I could’ve —”

“Gotten trapped in Lake Point and drop-kicked into the gutter with the rest of us?” Callie didn’t let her respond, because they both knew Leigh would’ve ended up managing a Taco Bell, selling Tupperware, and running a bookkeeping business on the side. “If you’d stayed here, you wouldn’t’ve gone to college. You wouldn’t have a law degree. You wouldn’t have Walter. And you sure as hell wouldn’t have —”

“Maddy.” Leigh’s tears started to fall. She had always been an easy crier. “Callie, I’m so —”

Callie waved her away. They couldn’t get entangled in another it’s all my fault/no it’s not your fault. “Let’s say social services has a report, or the cops put it in their notes that I was in bad shape. Then what? Where’s the paperwork now?”

Leigh pressed together her lips. She was clearly still struggling, but said, “The cops are probably retired or up the ranks by now. If they didn’t document abuse in their incident reports, then it would be in their personal notes, and their personal notes would be in a box somewhere, probably in an attic.”

“Okay, so I’m Reggie, the private detective that Andrew hired, and I’m looking into a possible murder that happened twenty-three years ago, and I want to see the police reports and anything the social workers have on the kids who were in the house,” Callie said. “What happens next?”

Leigh sighed. She was still not focused. “For D-FaCS, you’d file a FOIA request.”

The Freedom of Information Act made all government records publicly available. “And then?”

“The Kenny A. v. Sonny Perdue Consent Decree was settled in 2005.” Leigh’s legal brain started to take over. “It’s complicated but, basically, Fulton and DeKalb County were forced to stop screwing over children in the system. It took three years to hash out an agreement. A lot of incriminating paperwork and files conveniently went missing before the settlement.”

Callie had to assume any reports on her beat-down were part of the cover-up. “What about the cops?”

“You’d file a FOIA for their official documents and a subpoena for their notebooks,” Leigh said. “Even if Reggie tried to go the other way and knocked on their door, they’d be worried about being sued if they documented abuse but never followed up on it. Especially if it’s tied into a murder case.”

“So, the cops would conveniently be unable to locate anything, too.” Callie thought about the two officers who had interviewed her. Another case where men would keep their mouths shut to cover for other men. “But what you’re saying is, neither of those are a problem we need to worry about, right?”

Leigh hedged. “Maybe.”

“Tell me what you need me to do.”

“Nothing,” Leigh said, but she always had a plan. “I’ll take you out of state. You can stay in — I don’t know. Tennessee. Iowa. I don’t care. Wherever you want to go.”

“Fucking Iowa?” Callie tried to lighten her up. “You couldn’t think of a better job for me than milking cows?”

“You love cows.”

She wasn’t wrong. Cows were adorable. There was an alternate Callie who would’ve loved being a farmer. A veterinarian. A trash collector. Anything but a stupid, thieving junkie.

Leigh took a deep breath. “I’m sorry I’m so shaky. This really isn’t your problem.”

“Fuck you,” Callie said. “Come on, Leigh. We’re both ride or die. You got us out of this before. Get us out of it again.”

“I don’t know,” she said. “Andrew’s not a kid anymore. He’s a psychopath. And he does this thing where one minute he looks normal, and the next minute you feel your body going into this primal fight-or-flight mode. It freaked me the fuck out. The hairs on the back of my neck stood up. I knew something was wrong the second I saw him, but I couldn’t figure it out until he showed me.”

Callie took one of Leigh’s tissues. She blew her nose. For all of her sister’s intelligence, she had been in too many soft places for far too long. She was thinking of the legal ramifications of Andrew trying to open up an investigation. A possible trial, evidence presented, witnesses cross-examined, a judge’s verdict, prison.

Leigh had lost her ability to think like a criminal, but Callie could do it for both of them. Andrew was a violent rapist. He wasn’t not going to the police for lack of a smoking gun. He was torturing Leigh because he wanted to take care of this problem with his own hands.

She told her sister, “I know you’ve got a worst-case scenario.” Leigh was visibly reluctant, but Callie could tell she was also relieved. “I need you to taper yourself off the dope. You don’t have to quit altogether, but if someone comes around asking questions, you need to be straight enough to give them the right answers.”

Callie felt cornered, even though she was already doing exactly what her sister had asked. It was different when she had a choice. Leigh’s request made Callie want to dump her backpack on the floor and tie off right then and there.

“Cal?” Leigh looked so damn disappointed. “It’s not forever.

I wouldn’t ask if —”

“Okay.” Callie swallowed all of the saliva that had flooded into her mouth. “How long?”

“I don’t know,” Leigh admitted. “I need to figure out what Andrew is going to do.”

Callie choked back her panicked questions — A few days? A week? A month? She bit her lip so that she didn’t start crying.

Leigh seemed to read her thoughts. “We’ll take it a couple of days at a time. But if you need to leave town, or —”

“I’ll be okay,” Callie said, because they both needed it to be true. “But come on, Harleigh, you already know what Andrew is doing.”

Leigh shook her head, still lost.

“He’s in more trouble than you are.” If Callie was going to ride this out, she needed her sister’s lizard brain to kick in, the fight instinct to take over flight, so that it didn’t drag out too long. “He fired his attorney. He hired you a week before he goes to trial. The rest of his life is literally on the line and he’s throwing around these hints about cameras and getting away with murder. People don’t make threats unless they want something. What does Andrew want?”

Realization flashed in Leigh’s eyes. “He wants me to do something illegal for him.”

“Right.”

“Shit.” Leigh ran through a list. “Suborn a witness. Commit perjury. Aid in the committal of a crime. Obstruct justice.”

She had done that and more for Callie.

“You know how to get away with every single one of those things.”

Leigh shook her head. “It’s different with Andrew. He wants to hurt me.”

“So what?” Callie snapped her fingers like she could wake her up. “Where’s my bad-ass big sister? You just pointed a Glock at two meth freaks with a bunch of cops one street over. Stop spinning around like a playground bitch who just got her first broken bone.”

Slowly, Leigh started nodding, psyching herself up. “You’re right.”

“Damn straight I’m right. You’ve got a fancy law degree and a fancy job and a clean record and what does Andrew have?” Callie didn’t let her answer. “He’s accused of raping that woman. There are more women who can point their fingers at him. If this fucktard rapist starts whining about how you murdered his daddy twenty years ago, who do you think people are going to believe?”

Leigh kept nodding, but Callie knew what was really bothering her sister. Leigh hated a lot of things, but feeling vulnerable could terrify her to the point of paralysis.

Callie said, “He’s got no power over you, Harleigh. He didn’t even know how to find you until that douchebag private eye showed him your picture.”

“What about you?” Leigh asked. “You stopped using Mom’s last name years ago. Are there other ways he can find you?”

Callie mentally ran through all the disreputable avenues of locating a person who did not want to be found. Trap could be bought off, but, as was her habit, she’d checked into the motel under an alias. Swim Shady was an internet ghost. She had never paid taxes. She had never had an active lease or a cell phone account or a driver’s license or health insurance. Obviously, she had a social security number, but Callie had no idea what it was and her mother had probably burned it out long ago. Her juvenile record was sealed. Her first adult arrest listed her as Calliope DeWinter because the cop who’d asked for her last name had never read Daphne du Maurier and Callie, stoned out of her mind, had found this so hilarious that she’d pissed herself in the back of his squad car, thus halting all further interrogation. Add to that the weird pronunciation of her first name and the aliases piled onto aliases. Even when Callie was in the Grady ICU wasting away from Covid, her patient chart had listed her as Cal E. O. P. DeWinter.

She told Leigh, “He can’t find me.”

Leigh nodded, visibly relieved. “Okay, so keep laying low. Try to stay sharp.”

Callie thought about something Trap had said before he’d tried to rob her.

White dude. Nice car.

Reggie Paltz. Mercedes Benz.

“I promise it won’t be long,” Leigh said. “Andrew’s trial should last two or three days. Whatever he’s planning, he’ll have to move fast.”

Callie took a shallow breath as she studied Leigh’s face. Her sister had not really considered what kind of havoc Andrew could cause in Callie’s life, mostly because Leigh knew very little about how Callie lived. She had probably tracked down Callie through a lawyer friend. She had no idea Dr. Jerry was still working, let alone that Callie was helping him out.

Setting aside that Reggie Paltz was already asking questions, he clearly had his contacts inside of the police force. He could put Callie’s name on their radar. She was already trafficking drugs. If the right cop asked the wrong questions, Dr. Jerry could be looking at the DEA banging down his front door and Callie could be going through a hard detox at the downtown City Detention Center.

Callie watched Binx flop down onto his side, taking advantage of the sunlight hitting the dashboard. She did not know if she was more worried about Dr. Jerry or herself. They didn’t offer medically assisted detox in jail. They locked you in a cell by yourself and, three days later, you either walked out on your own power or you were rolled out in a body bag.

She told Leigh, “Maybe it would be better if we made it easy for Andrew to find me.”

Leigh looked incredulous. “How the fuck would that be a good thing, Callie? Andrew’s a sadistic rapist. He kept asking about you today. His own best friend says he’s going to start looking for you eventually.”

Callie ignored those facts because they would only scare her into backing down. “Andrew’s on bail, right? So he has an ankle monitor with an alarm that will go off if he —”

“Do you know how long it takes for a probation officer to respond to an alarm? The city can barely make payroll. Half of the old-timers took early retirement when Covid hit and the rest are covering fifty percent more cases.” Leigh’s incredulous look had turned into open bewilderment. “Which means after Andrew murders you, the cops can look up the GPS records and find out what time he did it.”

Callie felt her mouth go dry. “Andrew wouldn’t look for me himself. He would send his investigator, right?”

“I’m going to get rid of Reggie Paltz.”

“Then he gets another Reggie Paltz.” Callie needed Leigh to stop reeling around and think this through. “Look, if Andrew’s investigator locates me, then that’s something Andrew thinks he has on us, right? The guy will ask me some questions. I’ll feed him what we want him to know, which is nothing. Then he’ll report all of that back to Andrew. And then when Andrew springs it on you, you’ll already know.”

“It’s too dangerous,” Leigh said. “You’re basically offering yourself up as bait.”

Callie fought off a shudder. So much for trickling the truth. Leigh couldn’t know that Callie was already dangling from a hook or she would never let her stay in the city. “I’ll put myself in an obvious place so that the investigator can find me, all right? It’s easier to deal with someone when you know they’re coming.”

“Hell no.” Leigh was already shaking her head. She knew what the obvious place was. “That’s insanity. He’ll find you in a heartbeat. If you could see the photos of what Andrew did to —”

“Stop.” Callie did not have to be told what Buddy Waleski’s son was capable of. “I want to do this. I am going to do this. It’s not a matter of asking for your permission.”

Leigh pressed together her lips again. “I’ve got cash. I can get more. I’ll set you up wherever you like.”

Callie was not, could not, leave the only place she had known as her home. But she knew about another option, one that would make sense to anybody who had ever met her. She could leave Binx in the care of Dr. Jerry. She could take all the drugs in the locked cabinet and Kurt Cobain would be giving her a solo performance of “Come As You Are” before the sun went down.

“Cal?” Leigh said.

Her brain was too caught up in the Cobain loop to answer. “I need —” Leigh grabbed her hand again, pulling her out of the fantasy. “I need you, Calliope. I can’t fight off Andrew unless I know you’re okay.”

Callie looked down at their intertwined hands. Leigh was the only connection she had left to anything that resembled a normal life. They only saw each other in desperate times, but the knowledge that her sister would always be there had gotten Callie out of countless dark, seemingly hopeless situations.

No one ever talked about how lonely addiction could be. You were vulnerable when you needed a fix. You were completely unguarded when you were high. You always, no matter what, woke up alone. Then there was the absence of other people. You were isolated from your family because they didn’t trust you. Old friends fell away in horror. New friends stole your shit or were afraid you would steal theirs. The only people you could talk to about your loneliness were other junkies, and the nature of addiction was such that no matter how sweet or generous or kind you were in your heart, you were always going to choose your next fix over any friendship.

Callie couldn’t be strong for herself, but she could be strong for her sister. “You know I can take care of myself. Give me some cash so I can get this over with.”

“Cal, I —”

“The three Fs,” Callie said, because they both knew the obvious place had an entrance fee. “Hurry up before I lose my nerve.”

Leigh reached into her purse. She retrieved a thick envelope. She had always been good with money — scrimping, saving, hustling, only investing in the things that would bring back more money. To Callie’s expert eye, she was looking at five grand.

Instead of handing it all over, Leigh peeled away ten twenty-dollar bills. “We’ll start with this?”

Callie nodded, because they both knew if she had all the money at once it would end up in her veins. Callie turned in the seat, facing forward again. She slipped off her sneaker. She counted out $60, then asked Leigh, “Give me a hand?”

Leigh reached down and tucked three twenties inside Callie’s shoe, then helped her slide it back on. “Are you sure about this?”

“No.” Callie waited for Leigh to wrangle Binx back into the carrier before she got out of the car. She unzipped her pants. She tucked the rest of the cash like a pad into the crotch of her underwear. “I’ll call you so you have my phone number.”

Leigh unpacked the car. She put the carrier down on the ground. She hugged the lumpy pillowcase to her chest. Guilt flooded her face, permeated her breath, overwhelmed her emotions. This was why they only saw each other when shit got bad. The guilt was too much for either of them to bear.

“Hold on,” Leigh said. “This is a bad idea. Let me take you —”

“Harleigh.” Callie reached for the pillowcase. The muscles in her neck screamed in protest, but she worked to keep it off her face. “I’ll check in with you, okay?”

“Please,” Leigh said. “I can’t let you do this, Cal. It’s too hard.”

“‘Everything’s hard for everybody.’”

Leigh clearly didn’t like having her own words quoted back to her. “Callie, I’m serious. Let’s get you out of here. Buy me some time to think about...”

Callie listened to her voice trail off. Leigh had thought about it. The thinking was what had brought them both here. Andrew was letting Leigh believe that he’d bought her Iowa dairy farm story. If Trap was telling the truth, Andrew had already sent out his investigator to locate Callie. When that happened, Callie would be ready for him. And when Andrew sprung it on Leigh, she wouldn’t spin off into a paranoid freakshow.

There was something to be said for being even one tiny step ahead of a psychopath.

Still, Callie felt her resolve start to falter. Like any junkie, she always thought of herself as water finding the easiest path down. She had to fight that instinct for her sister’s sake. Leigh was somebody’s mother. She was somebody’s wife. She was somebody’s friend. She was everything that Callie would never be because life was oftentimes cruel but it was usually fair.

“Harleigh,” Callie said. “Let me do this. It’s the only way we can take away some of his leverage.”