Tech

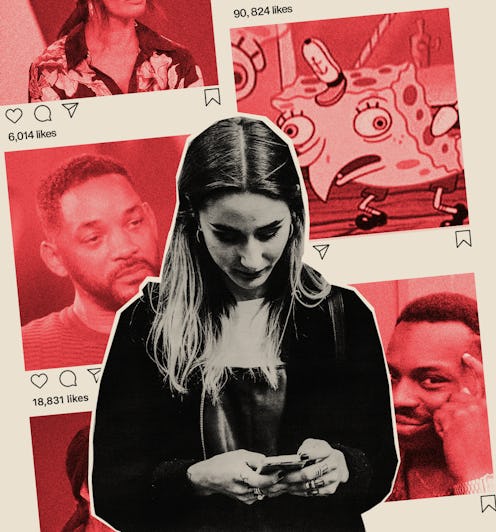

Are Memes Making Us Mean?

A reckoning of the way we communicate online could be on its way.

“Becoming a meme is one of my biggest fears,” I joked to a friend recently. In 2020, this is not an irrational fear. I was speaking shortly after Jada Pinkett-Smith and Will Smith had their now-infamous “entanglement” conversation on their family talk show Red Table Talk. After they discussed their marital issues and the nature of Pinkett-Smith’s relationship with musician August Alsina, a screen-grab of Smith’s pained face circulated online. Thousands of tweets later, Smith — one of the most successful actors on the planet — was inducted into the meme hall of fame. Admittedly I laughed, and something tells me Smith laughed about the silliness of it all too. Yet, as funny as it was, I still wouldn’t want it to happen to me. Which begs the question: when do memes stop being funny and start being harmful?

These days we use memes — humorous pictures, videos, and gifs sometimes accompanied by text — to say a lot without saying much at all. From Gemma Collins to Salt Bae, we all have a favourite. They’re an easy, digestible, and lazy way to participate in pop culture and, in the time of the coronavirus pandemic, memes frequently offer much-needed light relief.

Yet, to participate in meme culture is to understand that a picture of Spongebob could be used both in a tweet about a new reality TV show and a comment about the crisis in Syria. The widespread use of memes in this way means we’re at risk of becoming desensitised to people and their plights. Clearly, there’s a sinister side to memes that requires unpacking.

Rebekah Vardy, TV personality and wife of footballer Jamie Vardy, knows this first-hand. Who could forget the scandal between her and Colleen Rooney (former magazine columnist, TV personality, and wife of footballer Wayne Rooney) that broke to widespread mirth in 2019? In October, Rooney took to social media to accuse Vardy of leaking information about her private life to the media. With three crucial words (“It’s........ Rebekah Vardy”) the duo became embroiled in a very public row. Social media dubbed the feud "Wagatha Christie" in a nod to Rooney's apparent detective skills, and her original post reached hundreds of thousands of people, gaining nearly 300,000 likes on Twitter and 200,000 on Instagram.

Vardy, who was seven-months pregnant at the time, has always denied Rooney's accusations and is now suing for defamation. While thousands of social media users delighted in liking, sharing, and memeing the fallout, as Bustle reported in July, Vardy's legal team stated in documents handed to the High Court that the backlash left her feeling "suicidal" and that she "continues to suffer severe and extreme hostility and abuse as a result of the post."

Vardy's legal team isn't just claiming that she suffered because of the public nature of the accusations, but as a direct result of becoming a meme. "Many of Vardy's claims for damages rely on the extent to which Rooney's phrase 'Its... Rebekah Vardy' has become embedded as a meme in popular culture," read court documents. The case represents a high profile example of meme culture having its day in court, but it has the potential to be landmark for other reasons. We are not always privy to the impact becoming a meme has on the subject — could the awareness of Vardy's suffering impact meme culture in the future?

After all, memes are as much part of our online discussions as likes or hashtags. Whether we’re exposing "Karens" or praising Beyoncé's new video, memes are embedded in the conversation in a variety of ways. Many have tapped into their viral power and shareable nature to raise awareness of vital issues. But even here, the dark side of memes is never far away.

Earlier this year, during the increased momentum behind the Black Lives Matter movement following the murder of George Floyd at the hands of Minnesota police officers, social media was an important tool for sharing information. Alongside demanding justice for Floyd, we learned the story of Breonna Taylor, who was killed by Louisville police officers while sleeping in her home. The hashtag "sayhername" encouraged people to spread awareness, alongside the call-to-action "arrest the cops who killed Breonna Taylor."

However, as social media users and commentators began to point out, the same widespread sharing which helped raise awareness of Taylor's murder, also risked the campaign becoming a social media punchline. As Bryann Andreá tweeted in June: "Noticing a dramatic difference in tones and approach when it comes to “calling” for justice/bringing awareness to the #BreonnaTaylor case compared to some of the others. I can’t really put my finger on it, but I don’t like it. It’s giving me, “memes”. It’s not okay."

While Breonna Taylor’s story gained global attention and traditional media coverage thanks to social media, the main aim of the campaign — justice for her and her family — has still not been achieved. As Twitter user Natalie Whittingham Burrell wrote: "Y’all are turning #BreonnaTaylor into a meme and it’s counterproductive"

The harmful potential of memes has even been examined by academics at the University of Loughborough. In 2018, they presented a report to the UK government warning about the impact memes were having on teens' emotional development. While the study the report was based on looked at 13-16 year-olds, the applications for those of us in older generations are clear in the researchers' conclusions.

The group said they believe memes “normalise undesirable behaviours such as trolling, body shaming and bullying, and a lack of emotion may be indicative of a larger apathy with regards to such practice.” Interestingly the research highlighted the disconnect memeification can foster, noting that memes create a sense of happiness "regardless of the underlying tone or image used."

Memes happen almost entirely by accident, which makes them hard to control. The image, words, and/or name of any unsuspecting person can become internet fodder for use in contexts entirely divorced from their original meaning or intention. Frankly, this is what terrifies me the most.

Take, actor Kayode Ewumi — arguably one of the internet's most recognisable memes. You may know him as the character Roll Safe or the "Think About It" meme. If I show you, you’ll likely know the one. In 2015, when Ewumi was 21-years-old, he starred in a BBC mockumentary. A three-second snapshot taken from the show later went viral. Five years later and the meme is still widely used on social media in a variety of contexts.

While Ewumi experienced fleeting fame, memes don’t necessarily turn people into celebrities, but potentially permanent punchlines. As he explained in a recent interview with Seasoned BF: “I didn’t go to university to become a meme, I went to university to tell stories and become a storyteller. It is what it is... But, it makes people happy, right?”

Right. Memes do make people happy, but often at someone else's expense. And while they may often seem innocent, memes are all-too easily weaponised as tools of distraction, trolling, or bullying. Awareness of the real human impact of meme culture is growing, which poses a dilemma for meme-lovers. Can we continue to share them in the group chat without becoming part of the problem? It's a thorny question, with no easy answers.

"What we need is a moral and/or ethical filter," advises Dr Ash Casey, a senior lecturer in pedagogy at the University of Loughborough and one of the authors of the university's 2018 report into the potentially harmful impact of memes on young teens.

Dr Casey tells me that he believes the solution isn't stopping sharing memes entirely, but that internet-users do have a responsibility to be mindful of how they interact with others online. He also encourages meme-lovers to "challenge" harmful online content, especially when it "tap[s] into flawed stereotypes" concerning race, gender, sexuality, and disabilities.

He also reasons that this responsibility doesn't necessarily begin or end with the average social media user. "Thought leaders and journalists have a responsibility to promote memes that praise instead of ridicule and educate instead of divide. We need to create a world where memes are challenged when they do wrong and filters that stop the spread of divisive messages," he says.

The first step to addressing a problem is to admit that we have one. After all, memes are a by-product of society's well-documented toxic relationship with social media. Let's face it, we all seek and crave the validation a funny meme can bring. In a space where everyone is shouting to be heard, memes allow us to feel like we’re part of the conversation even when we don’t have much to offer by way of words. Yet, it's important to note, much like the cardinal rule of conversational kindness — if you don't have anything nice to say... well, maybe don't meme about it.