Life

6 Bizarre Beliefs About Work From History

It's spring, the birds are on the wing, and millions of college graduates across the world are removing their mortar boards and wondering how on earth they're going to land their first full-time job. The modern working world is filled with an astonishing array of possibility and new trends — from freelance to hot-desking, start-ups to flextime — and it can feel overwhelming to navigate it all. And that's totally normal — but to help put it all in perspective, you may want to learn a bit about what working life was like in previous eras.

Humans have been laboring for most of our history; the shift from nomadic life to settling down in one place for agricultural labor is determined to be one of the most defining moments in the history of our species, and from that beginning came "work" in all its forms, from merchants to middle managers. Societies have, however, come up with very different ways to cope with the working world, its demands, and what to do with their time off — from cursing slackers as demons to worrying about outdated tools coming alive and breaking things.

Stepping out the door to do a job has always been complicated, and our society is still very far from perfect when it comes to work. But if nothing else, we can be thankful that these days, asylums, ghost servants and poetry in job interviews are less common in the working world than they once were. (Though it does make CVs a little bit, well, boring.)

Rich People Could Make Dolls Do Their Dirty Work In The Afterlife

The ancient Egyptian concept of the afterlife was a deeply nuanced one, but its basic concept was that things were, in essence, the same for you after you died: you lived much after death as you did when you were alive. And that, for people of high status who were used to having all their work done for them, presented a problem. Left alone in the afterlife, they'd have to fend for themselves, which was frankly unacceptable. The solution? Figurines, known as shabti, which came to life after death and performed any filthy manual labor the deceased might be asked to do.

The word shabti means "answer," and shabtis were meant to be permanently available to answer their master's calls and the requirements of the gods; they were often miniature figurines of humans, sometimes carrying hoes or work implements. Found in Egyptian tombs throughout the centuries of the country's imperial glory, they often had spells written on their legs dictating their loyalty and their specific function. When public works were being built in the afterlife, the deceased could send in his or her army of shabti (there would often be a huge collection buried with one person) to do it all for them.

Manual Laborers Couldn't Experience True Leisure

Aristotle had a few intriguing ideas about leisure and its necessity to human flourishing, but he also had a very specific idea about what leisure actually meant. "Noble leisure," as he called it, was meant to involve only "pleasure, happiness and living blessedly," and you couldn't experience true leisure while you were at war, doing political derring-do, or involved in basically any other kind of work.

Noble leisure, however, wasn't the same as play or amusement. To be properly leisurely, Aristotle argued, required education: you had to spend your off-time doing things like writing poetry or discussing philosophy, instead of just keeping yourself cheered up after a long day at work. Children had to be educated on how to use their leisure nobly, but that kind of leisure was, Aristotle thought, out of reach to those who did manual labor and didn't have the assets of education.

Refusing To Do Your Job Could Cause Your Home To Be Infested By Demons

The Aztec Empire operated with a strict hierarchy system, in which everybody had their place and their prescribed duties. The pipiltin, or nobility, served the emperor and managed the work of the lower classes, or macehualtin, who made up the vast majority of the Aztec population and contained their own internal hierarchy, from merchants to slaves. These roles were seen as basically unbreakable — and if you decided you didn't want to work, or would prefer to do some other job, you risked becoming a literal terror.

No, I'm not kidding. Historians Scott Sessions and David Carrasco, in Daily Life Of The Aztecs, explained that the culture believed that "failure to conform to your place" would cause supernatural chaos. The result, they say, was "the release of harmful magical forces that could contaminate one's family or neighbourhood." People who refused to fit in and do their work could be designated as outcasts and named tetzahuitl: terror.

Civil Servants Had To Write Beautiful Poetry Under Pressure

If you thought your job interview was hard, spare a thought for the thousands of young Chinese men over the centuries, who sat the country's famous imperial examinations in the hope of becoming civil servants. The examination, which lasted in one form or another from the Han Dynasty in 200 BC to 1905, was made deliberately intensely grueling; a lot of young men's intellectual education at the time was designed purely to help them pass. And one element of the test that started in the Tang dynasty (and might strike fear into the heart of modern civil servants) was poetry composition.

The poetry section reflected the Tang's views on how essential verse was to the status of any educated man; everyone was expected to be trained in composing it. The examinations themselves required two types of poetry — one of 12 lines and another of 300 characters — but candidates were also judged on the beauty of their calligraphy. (If you develop horrendous handwriting due to nerves during a normal physics exam, you'll understand just how big an ask this was.)

Old Tools Could Come Back And Wreak Havoc

How long have you kept that hammer in your house? What about that wrench? If it's more than 100 years old, according to a belief popular in Japanese folklore in the medieval period, it may turn itself into one of the tsukumogami — once-useful household objects that have reached a century in age and acquired spirits to annoy their owners.

Japanese folklore recommends several ways to prevent tools from coming to life and causing problems: throwing out old ones every New Year in a ritual known as "sweeping soot," or taking them to the temple to be burned. They had to be careful, though — because tools that were merely 99 years old would be insulted by the idea of being thrown away and adopt a spirit anyway. The belief could, however, also be interpreted as a reward: that after 100 years of loyal service, a tool would acquire a soul and be reincarnated as something else — hopefully something not occupied with smashing your plates.

Overwork Could Drive You Mad — But Magnets Could Help!

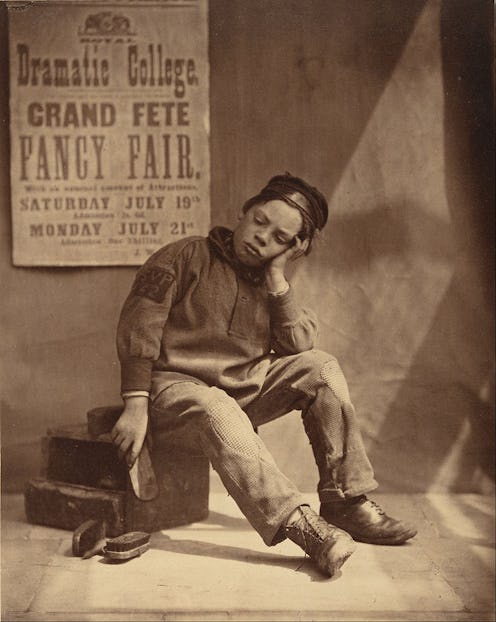

Victorian England was not necessarily a good place to have a high-pressure job. An absence of labor laws meant that working to the point of exhaustion was pretty common; but the problem of overwork attained a much bigger status, as it was seen as the root of nervous difficulties, breakdowns and complete insanity (particularly among men). Considering it something of a public health crisis, Victorian doctors came up with a plethora of suggestions on how to reduce the strain.

Records show that overwork was regarded by the Victorians as a supreme strain on the nerves, and could cause utter madness or complete exhaustion: young women who'd been diagnosed with it could be put to bed and forbidden to do anything, even sew, for weeks. (If they were lucky. Some women were sent to asylums for the same issue.) The root of it all, some doctors thought, was too much "brain work." Enterprising souls set out to find cures, from taking the waters at places like Bath to more obscure methods, like Hill's Genuine Magnetic Anti-Headache Cap. The headgear promised to relieve mental strain through the use of magnets, though how is not explained, probably because it's nonsense.