Books

The Best Cult Coverage Holds A Mirror To Real Life

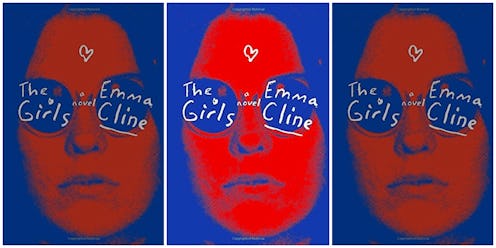

Cults occupy a strange, liminal corner of our collective imagination, shacking up with incense, robes, and droning hymns. They’re both a punchline ("drinking the Kool-Aid") and a punishing threat. They’re a bright, screaming extreme against which all other deviation is measured: "X may be bad, but at least it’s not the Westboro Baptist Church." With her breakout novel The Girls, Emma Cline isn’t the first author to coax the cultic experience into written word, but she’s unique in just how much she humanizes it. Cline’s barely veiled Manson family, headed by one Russell Hadrick, is solidly life-size. Those who pick up her debut novel seeking Bugliosi’s hard-boiled sensationalism will be disappointed. The rest of us will be intrigued.

Though shaped by the specter of an ending we all know is coming (a fictionalized version of Manson’s actual bloodbath), The Girls is anchored in an otherwise quotidian girlhood. Cline’s Evie Boyd makes a sullen, striving heroine reminiscent of her sharpest predecessors: she’s a more adventuresome Dolores Price, an ingenue Mary Karr. Evie’s struggle is our struggle, her story a microcosm of womanhood itself. Sordid cultic details form a muggy afterthought to the clarity of Evie’s inner life. The Girls is mostly a story about being, well, girls.

Personally, I wanted sordid cultic details. I’m a horror buff who reads true crime books before bed. The book left that particular itch unscratched, which disappointed me at first. In retrospect, though, I’m coming to see just how important — socially, culturally, artistically — Cline’s treatment of cults really is.

Lauren Drain, author of the memoir Banished: Surviving My Years in the Westboro Baptist Church, has caught flak for her perceived ambivalence about leaving the group. Though Banished ultimately spurns Westboro, it flirts with occasional apologetics. Drain, still a devout Christian, clearly values the bonds she forged on the picket line.

“The message behind Drain's story is confusing,” asserts Lindsay Deutsch in a USA Today review. “She did not leave the church by choice, and she admits that the WBC's rhetoric is ‘vitriolic, provocative, and shamefully insensitive’ and says she is relieved not to be a part of it anymore, but the book leaves the reader wondering if her beliefs would have changed on her own. One wishes she would more adamantly condemn the WBC's mission and the hateful actions in which she was an active participant.”

Liz Raftery of the Boston Globe agrees: “Though Drain clearly now feels a sense of remorse about her actions, as a reader, it’s often difficult to sympathize with her.”

Banished strikes a nerve because it refuses to divorce cults from normal human experience. Popular imagination draws a thick line between an ordinary religion and an abusive one, between brainwashing and bog-standard manipulation. Drain and Cline both complicate those distinctions. Drain has left Westboro Baptist, but refuses to denounce Christianity as an institution. Cline’s Evie Boyd muses, years after her involvement with Hadrick and co., that she was ultimately no different from the acolytes who carried out the story’s climactic slaughter. They place themselves, and their readers by extension, closer to the business end of violence than we’d like to admit.

A generation ago, literary treatment of cults took a significantly harder line. Our consensus on brainwashing and deprogramming, on distinguishing a cult leader from a mere charismatic, drew heavily on Dr. Robert Lifton’s research on prisoners in East Asia. Through his interviews with Korean prisoners of war and Chinese ex-cons, Lifton observed eight discrete components of brainwashing (or, as he called it, "thought reform"). His 1961 book Thought Reform and the Psychology of Totalism: A Study of "Brainwashing" in China introduced the term "thought-terminating cliche," among others.

By the 1970s, burgeoning anti-cult organizations were applying Lifton’s theories to new religious movements. “Father of deprogramming” Ted Patrick built an industry on wresting converts from their newfound families. Patrick stood multiple trials for kidnapping, but his business bloomed nonetheless. In post-sixties America, families grappled with the knowledge that the revolution,both sexual and spiritual, would simply not die quietly. Thus the phenomenon of, and the rising panic inspired by, the new religious movement.

Laurence R. Iannaccone of George Mason University wrote in his 2003 paper “The Market for Martyrs”:

...above all, the NRM’s attracted attention because they scared people. Their members often lived communally, devoted their time and money to the group, and adopted highly deviant lifestyles. ... By the late-1970s,public concern and media hype had given birth to anti-cult organizations,anti-cult legislation, and anti-cult judicial rulings. The public, the media, many psychologists, and the courts largely accepted the claim that cults could“brainwash” their members, thereby rendering them incapable of rational choice,including the choice to leave.

…

We now know that nearly all the anti-cult claims were overblown, mistaken, or outright lies. Americans no longer obsess about Scientology, Transcendental Meditation, or the Children of God. But a large body of research remains.”

Though cults, and new religious movements more broadly, no longer hold the terrifying sway they did a generation ago, our fictional treatments of them remain rooted in hyperbole. 2012’s Martha Marcy May Marlene stars Elizabeth Olsen as Martha, struggling with PSTD after her escape from a Jonestownian commune. The Netflix original The Unbreakable Kimmy Schmidt chronicles the titular Kimmy’s release from the apocalyptic preacher who’d kept her in a bunker for fifteen years. Kimmy and her fellow “Mole Women” dress and act like Anabaptist caricatures; her offhand mentions of“weird sex stuff in the bunker” are more than a little disturbing.

Both portrayals tap into what many Andi Zeisler, reporting for Bitch Media, considers a distinct trend. “A definite salaciousness tends to characterize media and pop culture representations of cults,” she wrote in February. Though we’re as likely nowadays to play the cult phenomenon for laughs as for tears, our focus remains largely outsize, anchored in the soapiest aspects, the most prominent cultural touchstones.

Juxtaposed against more lurid counterparts, The Girls is easily overlooked. It’s first and foremost, as mentioned earlier, a novel about girlhood. Its counterculture aspects fit squarely into your average 1960s bildungsroman. There’s no chanting, no uniformed ritual, just pot and occasional pederasty. Hadrick is a seductive older man, deftly wielding platitudes of peace and love to curry underage favor, but he’s no Svengali. “[S]o many [cults] take the form of outsized patriarchies whose entitlement to women's minds, bodies, and freedoms are extreme versions of social systems we recognize and repudiate”, writes Zeisler. If The Girls is anything, it’s recognizable. What young woman — or man, for that matter — flirting with the fringes of adult society hasn’t met the likes of Russell Hadrick? Who hasn’t been groomed just a little? Cline’s world, and Evie’s, exists not in a bubble but on a spectrum.

Iannaccone goes on to write:

In nearly all respects - economically, socially, psychologically - the typical cult converts tested out normal.

This isn’t to say that alternative movements don’t sow dysfunction and leave lasting wounds. It’s to say that mainstream ones do too. This is what anti-cult rhetoric so consistently forgets: wherever there is hierarchy, wherever there is community, there will of course be struggle. By narrowing our sense of outrage to fringe societies, we diminish the abuses all around us. Scientology may threaten its defectors, but so do many, if not most, major religions. The application of terms like Lifton’s “thought-terminating cliche” is similarly disingenuous: such sloganeering exists everywhere in society, not just in groups we happen to dislike. A parable of specks in neighbors’ eyes and logs in one’s own comes to mind.

In recent years, we’ve come to understand that sexual assault is so much more than a knife-brandishing stranger in the bushes. It’s both more common and less splashy than most media implies; as such, it’s increasingly difficult to spin it into an Other. Real pain is more insidious and more tenacious than that. Convincing the public that many victims know and even love their rapists is a tall order, but we’re getting there.

With Emma Cline’s Girls and Lauren Drain’s banishment, I’m seeing a similar evolution in how we think of cults. Drain was lambasted in the press for her seeming ambivalence toward the group she loved and left. Such criticism, though, relies on an inherently flawed, black-and-white model of cult membership and abusive dynamics generally. Fact is, there’s no hard-and-fast line between a healthy community and a toxic one. There’s no yellow CAUTION tape, no Greek chorus screaming to abort. The WBC can be both a vitriolic hate group and the home of everyone Lauren Drain has ever loved. Until we get more comfortable with ambiguity, we can’t fully understand or empathize with her story.

As for Cline and The Girls, I won’t pretend I didn’t expect a more satisfying end. From a literary perspective, it could have been splashier, the edges sanded just a touch less raw. From a personal one, though, Evie Boyd’s story is as foggy and imperfectly bounded as the best biographies. She grows up, finds community, builds a piecemeal life. She would probably pass Iannaccone’s test of normalcy: a job, a home, a handful of lasting if flawed relationships. She’s not as famous as Kimmy Schmidt or as overtly broken as Olsen’s Martha, but she’s something just as compelling: a fully-formed person.