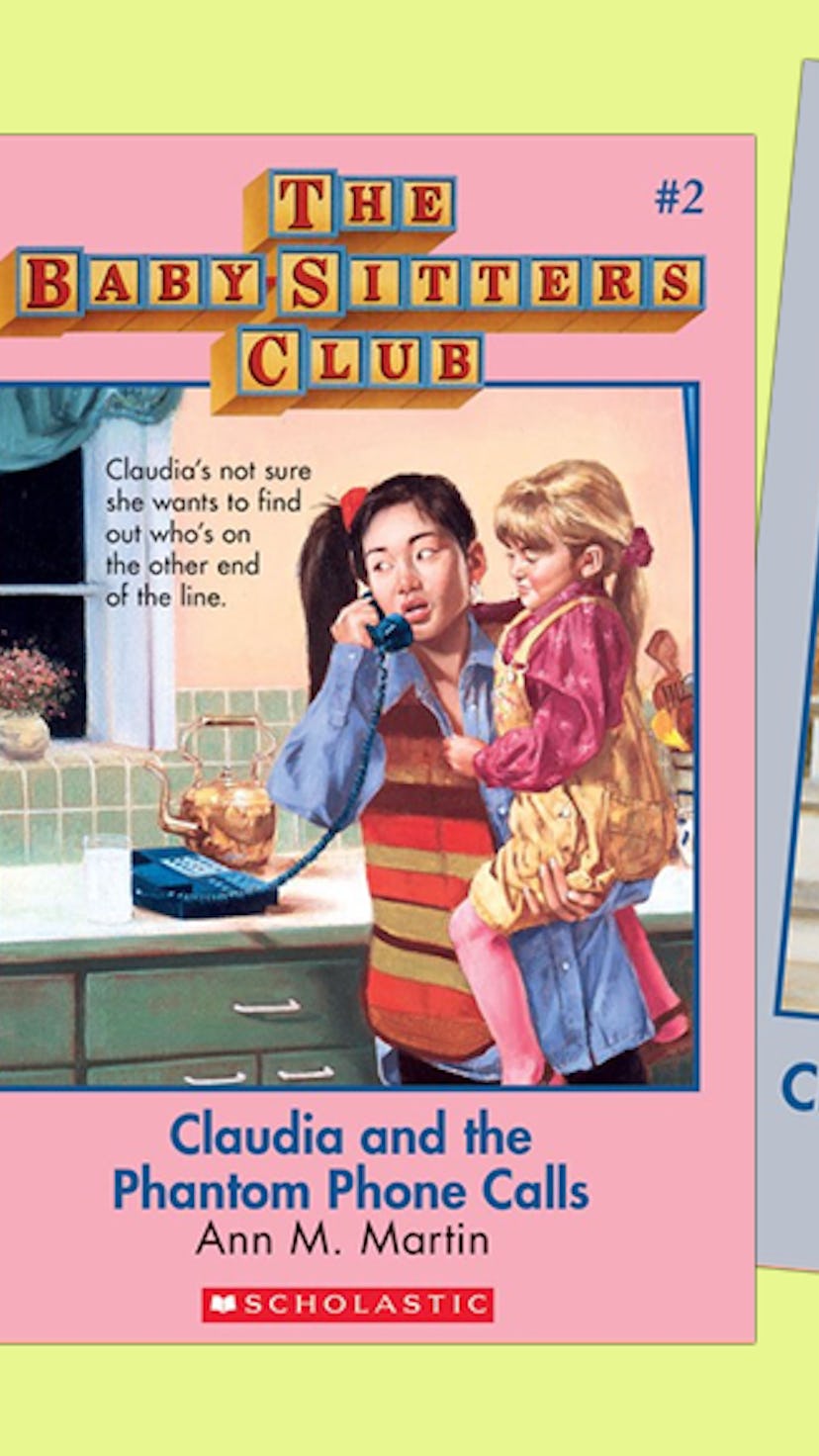

Books

How Claudia Kishi Inspired a Generation of Asian American Writers

Gale Galligan had to do a double take the first time she encountered Claudia Kishi in the pages of The Baby-Sitters Club series. Claudia — a Japanese American teen, who’s known for being the artsiest and wildest dresser among the group of fictional teens whose lives are chronicled in the books — instantly captivated Galligan, a multiracial Thai American. In all her years of reading, she’d never come across an Asian American character, much less one so artistic and aspirational. “I had to flip back the first time I realized, ‘Wait a second, she’s not white!’” recalled Galligan, who’s now the illustrator behind the graphic novel adaptation of Ann M. Martin’s popular young adult series.

When The Baby-Sitters Club debuted in 1986, there were few Asian American characters of note depicted in mainstream fiction, with the rare exception of the ones portrayed in seminal works like Amy Tan’s The Joy Luck Club. When Asian Americans appeared in books at all, more often than not, they were presented as dehumanizing stereotypes or one-dimensional sidekicks in books by white authors. Claudia, however, was different.

For Hollywood producer Naia Cucukov, the art-loving Claudia Kishi was “a guiding light” that helped redefine what young Asian American girls in popular culture could be and look like. “[She] breaks the mold of what we've ever seen in media as Asian women,” Cucukov, who is executive producing Netflix’s forthcoming reboot of The Baby-Sitters Club, tells Bustle. Today, Claudia remains a beloved touchstone for Asian Americans and many young readers of color who grew up with her, and her influence is still felt among those like Maurene Goo who write books today.

“As an adult who's writing YA now and always talking about writing diverse YA, I so appreciate that Claudia Kishi existed for me,” says Goo, whose romantic comedy novels all feature Korean American girls at the center. She praised Martin for giving her a role model — and one who upends the stereotype of the quiet, bookish Asian American teen.

With Claudia as a point of reference, Goo says she felt confident creating stereotype-shattering characters of her own.

When readers are first introduced to all of the babysitters in “Kristy’s Great Idea,” the first book of the series, Claudia greets narrator Kristy in a mish-mash outfit of “lavender plaid overalls, a white lacy blouse, a black fedora, and red high-top sneakers without socks.” It’s a getup that makes Kristy feel “extremely blah” in comparison. And unlike Kristy, Claudia has also started wearing bras and makeup and begun obsessing over the boys in their grade.

With Claudia as a point of reference, Goo says she felt confident creating stereotype-shattering characters of her own. “I knew that it wouldn’t be crazy to write a Korean American girl who was bad at school, who doesn’t give a crap,” she says, referring to the protagonist in her 2018 book, The Way You Make Me Feel. “It never even occurred to me to think, ‘Oh, is this a believable Korean American character?’” She credited Martin for conceiving of an individual like Claudia, who also defied her parents and struggled with academics. “The fact that Claudia was not the ‘model minority’ Asian kid and that she was cool and popular? That was mind-blowing,” says Goo.

Claudia also made a strong impression on Sue Ding, a documentary filmmaker who’s currently at work on The Claudia Kishi Club, an upcoming film about the iconic character. “Claudia was really the first character I ever encountered who not only looked like me but was also creative and cool, and — more than anything — a normal teenage girl,” Ding tells Bustle. Most of the non-white characters Ding read about as a teenager were those defined by their oppression or otherness. “They didn't really get to deal with everyday problems. They didn't get to have personalities beyond stereotypes of their race or ethnicity,” Ding explains. That’s why Claudia — who attends school dances with boys and stashes junk food in hollowed-out books to evade her disapproving parents — seemed like such an anomaly.

And though Claudia isn’t defined by her ethnicity, her background isn’t outright ignored either. YA author Sarah Kuhn — who related to Claudia as a Japanese American growing up in suburban Oregon — pointed out that Claudia’s ethnicity actually informs many of the character’s storylines. “You can't just swap her out for a white character,” says Kuhn, who’s best known for her Asian-centric Heroine Complex series. To Kuhn, Claudia’s Japanese American upbringing feels like an integral part of her characterization and not just an afterthought. To her point, Martin specifically explores Claudia’s identity and tackles racism in some of the later books of the series. “Keep Out, Claudia!” for example, saw a woman named Mrs. Lowell refuse to let Claudia and her black peer, Jessi, babysit her children.

Jean Ho, an LA-based writer who grew up admiring Claudia, also appreciated Martin’s depiction of Claudia’s family, an aspect she found particularly true-to-life.

“One of the most striking things that I remember about her was that she had a really close relationship to her grandmother, and her grandmother actually lived with her family,” says Ho. “In my household, we always had [extended] family members living with us temporarily,” she explains. “I feel like that's a very typical Asian American or immigrant experience, having a multi-generational living situation.”

“Many of the characters, including Claudia, were riffs on people from Martin’s life, whether from her childhood, or in her life at the moment, or kids she knew,” says Levithan.

So how did Martin, a white woman from New Jersey, dream up such a nuanced and realistic character? Although Martin was not available for an interview for this story, David Levithan — a senior editor at Scholastic — offered some insight into the creation of Claudia. Levithan, who edited the original Baby-Sitters Club series from 1993 until its conclusion in 2000, now edits The Baby-Sitters Club graphic novels published by Graphix, a Scholastic imprint.

“Many of the characters, including Claudia, were riffs on people from Martin’s life, whether from her childhood, or in her life at the moment, or kids she knew,” says Levithan. Cucukov, who met and consulted with Martin for the Netflix series, couldn’t confirm whether someone from the author's life had inspired Claudia in particular, but she commended Martin for putting time and care into her writing. “She did her homework. She researched. She talked to people. A lot of what's in there is stemming from either people she knew or situations she knew kids were dealing with,” says Cucukov. That effort is in part why Claudia resonated with so many readers.

“I think so many of us did find Claudia by ourselves, and that's kind of why she was so important to us,” says Ding.

But the radicalness of Claudia may not have been immediately apparent to Asian Americans like Ding who grew up in a homogeneous community and read The Baby-Sitters Club in isolation. Although Ding instantly gravitated toward the artistically inclined teen, it wasn’t until she read Yumi Sakugawa’s homage to the character, a 2013 comic titled “Claudia Kishi: My Asian American Female Role Model,” that she began to understand how Claudia may have shaped her.

“I think so many of us did find Claudia by ourselves, and that's kind of why she was so important to us,” says Ding. “But now because of the internet … there's this whole generation of people who speak about her as an inspiration and who are creating really amazing work of their own.”

In a way, Claudia illustrates just how far ’80s and ’90s pop culture had gone in terms of Asian American representation, and how far it has yet to go. It’s a topic that hits close to home for Ding, who began working on her documentary as a way to call for more inclusivity and diversity in media, in terms of both creator representation and onscreen representation. According to Ding, there are real-life implications when people don’t see themselves reflected in the entertainment they consume. “It's not just that we don't feel good when we don't see ourselves represented," she says, "it's that it really affects what we think of as possible for ourselves."

Kuhn agreed that the dearth of Asian American representation in books also shaped the way she viewed her prospects in writing. “The things I liked to read — sci-fi, fantasy comics books, and romance books — were not really [genres] where I saw Asian American girls centered,” says Kuhn. “So I don’t think I knew I could tell stories about girls who looked like me.” But Claudia provided creatives like Kuhn and comic artist Galligan with a sense of validation and belonging that inspires them to this day.

“Growing up knowing that she was a person on the page who could be me meant the world,” says Galligan. Claudia’s existence assured Galligan that, “no matter what you do, you can make creative choices, you can be yourself, and you're always going to find people who accept that about you and believe in you.”

This article was originally published on