Life

The Internet Is In Love With A 6-Year-Old Skeptic Who Called Santa “Em[p]ty" In His Letter

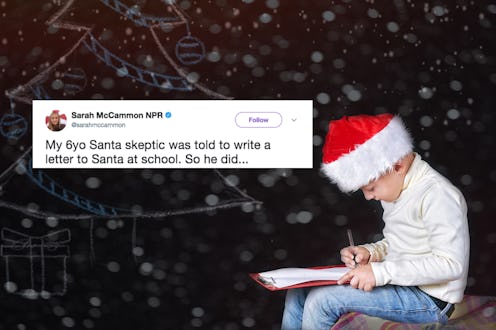

For many children who celebrate Christmas, writing an annual letter to Santa Claus is a time-honored tradition engaged in for as long as they believe in the jolly guy in the red suit — and often for some time afterwards, as well. (If you’ve got siblings who still believe, you’ve got to keep up the act, right?) But this 6-year-old’s letter to Santa? It is… unlike any other letter to Santa you’ve probably seen before. It is truly, truly savage — so naturally, it’s going viral on Twitter.

Sarah McCammon is a reporter who currently covers the Mid-Atlantic and Southeast regions of the United States for NPR’s National Desk; she primarily focuses on politics (she was NPR’s lead reporter assigned to the Trump campaign during the 2016 election cycle), but according to her NPR bio, she also covers science and health, including abortion and reproductive health.

She’s also got kids, one of whom is responsible for the letter in question. The letter was apparently an assignment the 6-year-old was given at school last week (on Nov. 29, to be exact); McCammon subsequently bestowed upon us the glories of her child’s creation on Dec. 3 via Twitter, and honestly, I am still recovering from it. It’s that good. It’s the kind of letter to Santa I imagine Wednesday Addams might write, full of gloom and doom and decorated with a delightfully morbid combination of holiday wreaths and skulls.

Here, take a peek:

I mean… just read McCammon’s translation of her child’s letter again:

“Dear Santa,

Santa Im only doing this for the class. I know your nottylist is emty. And your good list is emty. And your life is emty. You dont knowthe trouble Ive had in my life. Good bye.

love

Im not telling you my name”

And then check out McCammon’s follow-up tweet:

As the youths say: I AM DEAD.

I am also (unsurprisingly) not the only one who was completely and utterly slayed by the existential dread expressed in this “Dear Santa” letter — but even better is the fact that so many other parents and adults with kids in their lives began sharing their own similarly hilarious tales in response. Like this one:

(True; we believe the historical Saint Nicholas died on Dec. 6, 343.)

And this one:

I also appreciate this observation about McCammon’s offspring’s illustrations:

This kid has reached a level of angst even angsty adults can only dream of achieving. Well played, young one. Well played, indeed.

The history of children writing letters to Santa goes back more than 150 years — and, indeed, as Alex Palmer noted at Smithsonian Magazine in 2015, “Notes sent to Santa are an unlikely lens through which to understand the past, offering a peek into the worries, desires and quirks of the times in which they were written.” What’s more, Palmer observed, the “changing ways adults have sought to answer [these letters] and their motivations for doing so” can be just as fascinating.

Santa himself — a sort of combination-slash-reimagining of the real-life bishop Saint Nicholas, the Father Christmas character who personified the spirit of the holiday from about the 15th century onward in England, and the Sinterklaas figure of Belgium and the Netherlands — was originally much more of a disciplinarian to children from the United States; indeed, the earliest Santa letters we know of, which date back to the early-mid 19th century, were actually from Santa and addressed to the children. The letters gave the children assessments of their behavior and advice on how to improve going forwards.

Letters written by children and sent to Santa became more of a thing as the U.S. Postal Service evolved — but it was around 1871 that the practice really started to pick up. In December of that year, Harper’s Weekly published an illustration by Thomas Nast depicting Santa sorting his mail into two piles: “Letters from Naughty Children’s Parents” and “Letters from Good Children’s Parents.” Nast’s Santa drawings had been a staple of the magazine for years at that point, but this particularly illustration had a profound impact: According to Mental Floss, the volume of letters to Santa post offices reported receiving increased dramatically the year following the illustration’s appearance.

Although initially, most Santa letters received by post offices were sent to the Dead Letter Office and destroyed — it is, after all, illegal to read mail addressed to someone else, even if that person is mythical or dead — eventually adults started to feel not great about that; as Palmer put it at Smithsonian Mag, “By the turn of the 20th century, the public and press began complaining that children’s wishes were treated with such neglect.” So, in 1913, the policy was officially changed: After having received the approval of the local postmaster, charitable groups could read and answer the letters. Some 15 years later, after the (non-U.S. Postal Service-related) creation of and trouble with the Santa Claus Association in New York — a huge amount of donation money raised to fund the association went missing and was later found to have lined its creator’s pockets — Operation Santa Claus was launched by the Postal Service to handle Santa letters. This year marks the 105th anniversary of Operation Santa Claus’ creation.

Honestly, I really want to know how the Postal Service deals with letters like McCammon’s child’s. Do they have a Santa Letters Hall Of Fame or something? Because if there is, this one definitely deserves to be in it.