News

Here's Why The "Monopoly Woman" Crashed That Equifax Hearing

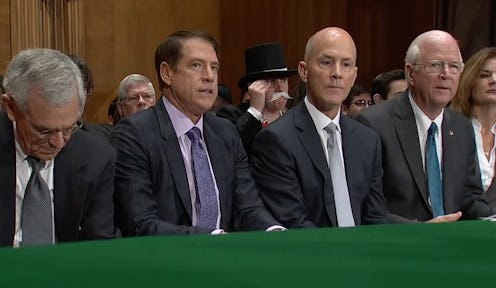

Activist Amanda Werner stole the show as the "Monopoly Woman" at the Senate's Equifax hearing on Wednesday after showing up dressed as the famous board game character. As the credit reporting agency's former CEO Richard Smith testified before the Senate Finance Committee about Equifax's massive data breach, which affected more than 140 million people, all eyes were on Werner, or should I say, Uncle Pennybags.

Wearing a black top hat, red bow tie, and gold monocle, Werner twirled her white mustache in the background of the proceedings. While the internet had a field day with the images, Werner was actually there for a lot more than laughs. A campaign manager for Public Citizen, a consumer rights advocacy group, Werner was speaking out against forced arbitration and how it exploits consumers in favor of big corporations.

Holding a yellow "Get-Out-of-Jail-Free" card with the logos of Equifax and Wells Fargo on it, Werner explained to the press that "forced arbitration allows companies to break the law and not have any consequence because consumers can't actually go to court."

Arbitration is a method for resolving disputes in which two parties present their sides of an issue to an arbitrator or panel of arbitrators, according to ConsumerAdvocates.org. Forced arbitration is when a company requires an employee or consumer to submit any dispute to the private arbitration forum that they've funded. Consumers are forced to waive their right to sue, appeal, or participate in a class action lawsuit. It's mandatory, the arbitrator's decision is binding, and results are not made public.

Forced arbitration clauses are often included in the fine print of contracts and agreements, as was the case with Equifax. Following the security breach, during which hackers stole the names, dates of birth, addresses, Social Security numbers, and credit card numbers from millions of customers, Equifax offered free identity theft protection and credit monitoring to affected consumers, CNN reported. However, the agreement came with an arbitration clause that prevented customers from suing or joining a class-action lawsuit.

While the company later removed the clause after backlash, it's still included in other consumer products, according to CNN. Smith told Senators in September that the forced arbitration clause was not designed to be applied to the breach. "Equifax is a great example," Werner said. "They bury a forced arbitration clause deep in the fine print of a consumer agreement that no one ever reads, and people lose their right to a day in court and didn't even realize it."

Werner calls this a "rigged system" that leaves consumers with little to no options. "There's very little opportunity to appeal a case if they decide wrong, and you have barely a chance to present your evidence," she told press outside the courtroom on Wednesday. "In fact, a recent study from the Economic Policy Institute found that the average consumer ends up ordered to pay the bank or lender $7,700 in arbitration."

She explained that while someone discovered the forced arbitration clause in Equifax's agreement, that's not always the case. Three years before Wells Fargo was caught creating millions of fake accounts in customers' names in 2016, consumers had been attempting to sue the company over the fraudulent accounts. "Because those consumers were forced into a secret arbitration system," Werner explained, "[Wells Fargo was] allowed to continue defrauding customers for another three years."

In a release on Public Citizen's website, the organization's president, Robert Weissman, reiterated Werner's point that "forced arbitration gives companies like Wells Fargo and Equifax a monopoly over our system of justice by blocking consumers’ access to the courts." He explained that the Trump administration is currently attempting to use the Community Reinvestment Act resolution to roll back the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau's arbitration rule, which allows consumers to choose between arbitration, individual legal actions, or class-action lawsuits. "[It's] a virtual get-out-of-jail-free card for companies engaged in financial scams," Weissman said. "It should not pass go."