Books

Your Fave Nursery Rhymes Are Actually Teaching Children Some Sinister AF Lessons

What's your first memory of being told a story? Chances are it was listening your parents or another adult read to you at bedtime. The way most people first experience fairytales and nursery rhymes is via the spoken word, which taps into a long tradition of oral storytelling. Sometimes those bedtime stories were soothing. But other times, behind the gingerbread and glass slippers, there was something darker and more disturbing at play — with sinister motives and dire consequences for the slightest missteps.

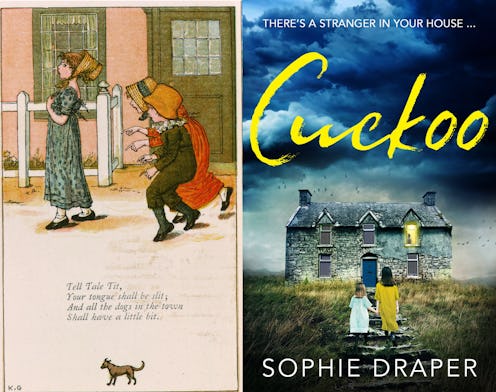

Writer and storyteller Sophie Draper's debut novel Cuckoo sees nightmares in the nursery become the source of waking terror for Caro, who returns to her childhood home following the death of her stepmother Elizabeth. Draper's work taps into both the light and the dark of traditional storytelling. Here she explores how nursery rhymes and the gruesome imagery disguised by jaunty rhythm and rhyme can shape our understanding of the adult world.

There’s something dark in the nursery. Things that go bump in the night. An old woman living in a cottage with chicken-leg stilts, a stepmother cooking up little-boy stew. Never mind the three talking severed heads floating in a well. Fairytales that haunt us with images that linger long after their supposed happy ending.

When I was about four, I slept in a tiny box room under the eaves with curtains that featured swans on a lake. The swans were brown and red, caught in a winter storm, the trees almost vertical across the water, dead leaves blistering in the wind. The birds weren’t graceful but tormented, like in the story of the twelve brothers turned into swans by a witch. In my head, a rhyme repeated over and over again:

"Matthew, Mark, Luke and John,

Bless the bed that I lie on.

Four corners to my bed,

Four angels 'round my head.

One to watch and one to pray,

And two to bear my soul away."

At that age, I had no idea what a “soul” was, but it sounded like those swans were waiting to catch the threads that frayed at each corner of my blanket, to sweep me out over that brooding, black lake.

Why do we do this to our children? Sing them songs and tell them tales that are so dark and gruesome?

"What are little boys made of? What are little boys made of?

"Snips and snails and puppy-dog tails, that’s what little boys are made of.

"What are little girls made of? What are little girls made of?

"Sugar and spice and all things nice, that’s what little girls are made of."

As my mother recited that, I saw boys made of animal body parts and a little gingerbread girl with her head bitten of. Traditional stories and rhymes have always been highly visual — it’s what makes them so memorable, that and the beating rhythm of those words:

"Ding, dong bell, pussy’s in the well. Who put her in? Little Johnny Flynn!"

(You’ll find that one in my book, Cuckoo.)

It’s those little lurid titbits that grab your attention, listening again and again as the young mind tries to process the words and their meaning; the rhymes and tales that stand the test of time, remembered because they’re so compulsive and something resonates.

There’s one nursery rhyme I loved, a joyous pattern of words:

"This old man, he played one,

He played knick-knack on my drum.

With a knick-knack, paddywhack, give a dog a bone.

This old man came rolling home…"

Until I learnt that “knick-knack” means a beggar playing bones, and “paddywhack” was a phrase for hitting someone hard. And the old man rolling home? Either kicked out unkindly, or drunk. This was a rhyme born of violence and poverty.

Even worse is this one:

"Tell Tale Tit!

Your tongue shall be slit;

And all the dogs in the town shall have a little bit!"

I remember it from school, kids baiting one another or picking on one child in particular. But the rhythm, the tune with which it’s said, is irresistible, isn’t it?

Perhaps we’re innocently repeating the taunts of another era, or simply teaching our children that this exciting new world is in fact a darker place, where loved ones die, and friends and families betray each other, and to win a fortune or fall in love, means a long, arduous journey. That’s real life, isn’t it?

So how about this one as a grim life lesson:

"Solomon Grundy, born on Monday, christened on Tuesday, married on Wednesday, took ill on Thursday, grew worse on Friday, died on Saturday, buried on Sunday."

What a fantastic, terrifying summary of what to expect in life.

You can find out more about the author at sophiedraper.co.uk