Life

Why I Still Love Christmas As An Atheist

When I was seven, I prayed for batteries. I could have prayed for a pony if I’d been greedier. I could have prayed for starving children if I’d been more selfless. Instead, I chose to focus my spiritual energy on replacement C alkaline batteries for my red, plastic flashlight. I pictured the Eveready brand, but I was willing to defer to God's judgment on the matter. To make sure God knew I was in it for the right reasons, I crammed a few singles and some change into the empty battery compartment for him to take in exchange for the humble miracle I requested. I didn't want God to mistake my effort to commune with him for simple cheapness.

You're probably not surprised to find out it didn't work out as I’d hoped. I, however, was sincerely shocked to hear the jangle of change when I shook my flashlight the next day.

Though I was a devoutly religious child — attending church every week, praying when I was troubled, and repeatedly reading a biography of 19th century famed Italian Catholic, Don Bosco, under the fort I’d built out of afghan blankets — I have to admit it wasn’t the sense of community or the moral guidance that attracted me the most to the Catholic church. It was the magic.

The idea that there's an all-knowing, all-seeing God who's willing to forgive you for any horrible act if only you repent and change your ways appealed to me. I was also perversely thrilled that the devil competed against him for my very soul, and I had to fight him at every turn as he attempted to guide me into wrongdoing. It wasn’t only deities who were capable of such supernatural powers, either. Future saints, like Don Bosco, could perform miracles. In fact, they had to perform no fewer than three in order to be canonized. I believed in all of it, and I wanted in.

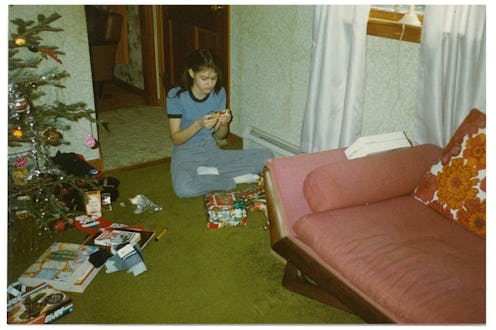

But my most cherished childhood Christmas memories aren’t of going to church. They're of listening to the Gene Autry Christmas album while my mom taped plastic candles to the windowsill (inevitably taking off some of the wood finish during the process). They're of my stocking (which featured a sassy, felt elf) going up with my name printed clearly on it so that none of the gifts intended for me would fall into the wrong hands. They're of my brothers and I waiting impatiently for my mom to wake up so we could open our gifts after shaking them, savoring them, and wondering about them. Even though they would turn out to be ordinary things — socks, toys, records — I remember the feeling that they could be anything. Something I’ve never even heard of, something I’ve never seen! Or, something wonderful that I didn’t even know I wanted.

Part of my family’s Christmas tradition was that my mother never claimed that Santa brought us gifts. Instead, she told us that God brought them. I can’t recall if this was to staunch annoying logistical questions from my brothers and I about the relative speed of reindeer travel, or how many intellectual property violations lawyers worked at the North Pole since the elves were clearly making Legos and Barbies in their toy factory, or if it was simply a logical extension of her lifelong propensity for straight shooting. (The same propensity which prompted her to ask us, even as preschoolers, not whether we had to pee but "urinate.")

Effectively, though, I still believed the gifts came from an unseen source, until a girl from my Brownie troop showed me the stash of wrapped presents in her hall closet one fateful December day. At that point, I knew our gifts were actually from an unimaginably pedestrian source — our parents, via the mall.

As crushed as I initially was, by the time Christmas rolled around, I’d moved on. My stocking was still stuffed on Christmas morning. The lights still blinked on the tree. I’d watched Santa Claus is Coming to Town a few times, and it was as good as ever.

Call me a pragmatist, but it didn’t really trouble me to discover that all that bounty was the work of humans. My grandparents still came over. There was plenty of good cheer. I mean, there was still pie, wasn’t there? It was OK that it was just us. It still felt pretty magical to me.

No matter what you believe, right now is all we have, always, and if everyone acted the way you’re supposed to on Christmas, right now would be pretty great.

I'm not going to say I literally became an atheist after I discovered that God wasn't personally selecting my board games, but it might have started the ball rolling. Shortly after that, I began rejecting church doctrine, partly out of suspicion it wasn't true, and partly, it must be said, out of spite.

Original sin seemed downright unfair. Why am I already guilty of something someone else did when I was doing my best to keep the commandments, and, let's face it, at the age of 10, felt like I'd led a pretty sin-free life? Why were so many of the commandments about worshipping God? If he's so all-powerful, why does he care if we acknowledge him or not? And how can it be that everyone who doesn't follow our particular traditions could be banned from heaven, when after all, it was pure chance that I did, based on my upbringing?

It wasn't long before I was calling out the whole system, and its underpinning, the concept of God itself.

At first, I missed the idea that there was a whole other world that was invisible to me. But it wasn't long before I realized there were plenty of magical things left in the world that were verifiably true. Undiscovered species! Hidden cities! Miraculous scientific advances! I didn't need God to feel the world was an amazing and mysterious place.

But even though I've given up praying and wearing crosses, along with most other American atheists and agnostics, I've never seriously considered giving up celebrating the holiest day on the Christian calendar. Why would I? If anything, the trend toward taking Christ out of Christmas is gaining steam. As more and more millennials give up on religion altogether, and the numbers of atheists and agnostics grow, maybe, someday, Christmas will be a purely secular holiday. As much as the War on Christmas faction would have you believe otherwise, it would hardly change anything. At this point, for most people, Christmas is more of a cultural holiday than a religious one.

At Christmastime, people really are kinder and more cheerful. Most of us prioritize spending time with the people we like and love. There are stories every year about someone paying off all the items on layaway at their local department store just to be nice. Christmas is so powerful it prompted a truce in World War I on the Western Front. No matter what you believe, right now is all we have, always, and if everyone acted the way you’re supposed to on Christmas, right now would be pretty great. The power of that, and the good cheer that goes with it, is as real to me as it is to anyone who believes in a higher power.

Though I don’t believe in God, on Christmas, I understand the idea of God’s unconditional forgiveness, a concept which seemed so incredible to me when I was a kid. When I see people dropping off donations at their local homeless shelters, hugging their friends and neighbors in holiday greeting, sacrificing so their kids can get just what they wanted on Christmas morning, I feel a true love for humanity. I forget about every act of war, of injustice, and every way we've failed. Though it’s not in my power, if I could, I’d forgive us for everything.

So this Christmas, I won’t be reading the Origin of the Species and eating a nutritious meal off a Richard Dawkins placemat. I’ll be cheerfully singing carols along with the radio. I’ll be surfing cable for A Charlie Brown Christmas. I’ll be sending gifts to loved ones, excited for them to receive what I’ve picked. I hope before they open their packages, they shake them and wonder. What could it be? And I hope they’re OK with the fact that their gifts came from me, instead of Santa.

Images: Nancy Matson