Movies

Amy Tan Knows Stories Say More Than Words Alone. Now, She’s Telling Hers.

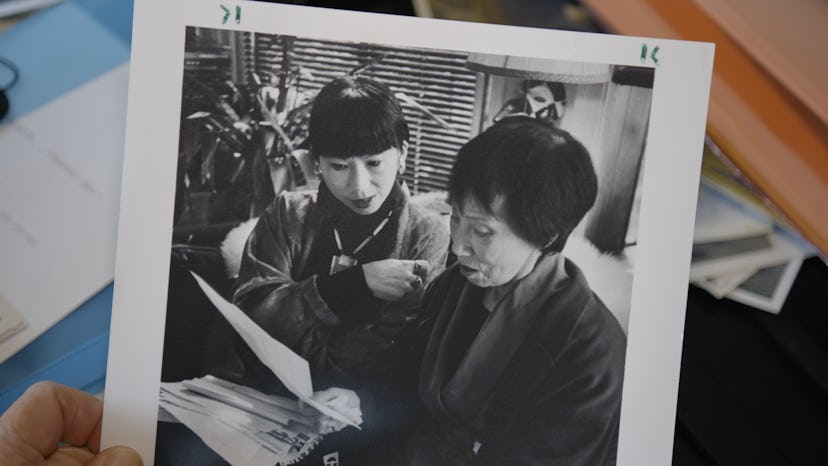

Amy Tan: Unintended Memoir is a linear and intimate portrait of the author’s life.

“I’m a pretty normal person,” Amy Tan says, with a heaping mound of humility. The writer has published six novels, two children’s books, a memoir, and accumulated a smörgåsbord of nominations and awards, including the Commonwealth Club Gold Medal — but as she’ll tell you, Tan isn’t just a writer. On any given day, she’s also an artist, singer, linguist, reader, activist, wife, daughter, or amateur ornithologist; even as she’s pigeonholed by the public, Tan insists her identity fluctuates with her activities and surroundings.

Regardless of how she views herself, Tan is an icon. And that is immutable.

This tension between selfhood and public identity is fertile ground for Amy Tan: Unintended Memoir, which premieres on May 3 as part of PBS’ “American Masters” series. The intimate portrait of the author’s life is directed by the late James Redford, in his final project. Tan’s legacy is one that can’t be refuted or even argued. A trailblazing figure for AAPI writers, she found her writing had near-universal appeal. The Joy Luck Club, Tan’s first and arguably most beloved novel, remained on the New York Times’ Best Sellers List for over 40 weeks after its initial release in 1989. The 1993 film of the same name, which Tan co-wrote, received equal praise, and was preserved by the Library of Congress’ National Film Registry last year.

Chilean writer Isabel Allende — one of Tan’s friends and colleagues featured in Unintended Memoir — says the way Tan writes about family appeals to people of all backgrounds. “Those grandmothers are like my grandmothers, and that makes it so close, so personal, so touching in so many ways,” Allende explains. “I think that’s what every reader feels anywhere in the world, in any language, when they read Amy.”

Crazy Rich Asians writer Kevin Kwan and the film cast of The Joy Luck Club also sing Tan’s praises. But Unintended Memoir doesn’t solely focus on the good. Audiences also see the distressing parts of her life, like the years of experienced and inherited trauma she endured as a child that carried into her adulthood, or the critiques from fellow AAPIs that The Joy Luck Club promotes Chinese and Chinese-American stereotypes and exotification. Tan, however, isn’t shy about the documentary’s less flattering parts. In fact, she welcomes the conversation, acknowledging these hardships are just as responsible for shaping her identity and success.

Speaking via Zoom from her home in San Francisco, Tan, now 69, talks to Bustle about her many identities, from her passion for language, to her time spent as the lead singer for an all-author band, the Rock Bottom Remainders, to her love of birds and sketching.

In the documentary, you said felt wary of identifying as a writer in your early career, even after The Joy Luck Club. Would you say you identify as one now?

As a writer? I definitely do, but I also think of my identity as being so many different things. The way I think of myself isn’t singular, and it always depends on the context. In one situation, I might be Chinese-American, as that could be the most important part of myself in that context. In others, I’m a writer, or a daughter, or a woman. But yes, I definitely look at my life’s work as that of a writer.

In addition to your creative legacy, the documentary delves into your academic background. You have two advanced degrees in linguistics. How has your understanding behind the science of language and its structure shaped the way you write?

You know, no one has ever asked me that question. And I think it’s so important. Even from the time I was a little kid, I have been fascinated with language. Words are supposed to convey so many things and how we use them to express ourselves, including emotion, and how we report things, like lies or facts. I have always been in love with the nature of language, as well as languages. It’s a very important reason why I love the craft of writing, and the way I think about language as imagery. It began with a love of language, and a feeling that words were inadequate to express what I really felt. It takes a whole story to set the context of what these words actually meant.

On a more personal note, one of the prominent aspects that’s explored in the film is the relationship with your family, particularly your mother. Could you describe the experience of revisiting your early life through the lens of the film?

There were a number of moments that caught me off guard. James Redford, the director, had taken a lot of material, like old VHS tapes I was actually going to throw away, and he had them digitized and put in the film. There’s a segment of my mother talking in the living room in 1990, and I’m the person behind the camera watching and listening to her. And I was able to relive that in the documentary, and remembered how, at the time, I said nothing, or as little as possible. The viewer of the documentary might think that I’m bored, as she’s talking about very dramatic moments. I would just nod along silently. But I was silent because I didn’t want to interrupt her. She had this wonderful quality of going into a space of memory and reliving it as if she was there again. All the fullness and emotion from those moments are there. I loved hearing her voice again, and hearing these truths that we said to each other for so many years, and often not with understanding.

The documentary also features interviews from established writers and friends, or both, like Kevin Kwan. You once mentioned in a press conference that the public often groups your work and Kwan’s in the same place, and through that, you’ve struck up a friendship. I’m curious to know how this friendship developed, and the things you’ve learned from him along the way.

I read Crazy Rich Asians when it first came out, and I loved it. I was almost hesitant to say so at the time, because I didn’t want people to assume that I only loved it because it was about other Asians. But it’s a really fun book with a comedic look at society human nature. I know a number of people who were or still are like those people in the book. I saw the movie probably five times. Kevin and I naturally became friends once we met, but what eventually happened that was quite wonderful is that he got me involved in some of the AAPI campaigns during the election. I was already doing volunteer work for another campaign, for both the general election and for Georgia. So Kevin and I started doing them together. We’d show up at events where people were learning to do phone or text banking, and we’d encourage and thank them together, which was fun. We share a similar view of politics and our need to be active in those politics.

You also talk about this metaphorical pedestal that AAPIs placed on you to be a “the voice” of your community, as well as the critiques posed against The Joy Luck Club that it perpetuates stereotypes. I sometimes feel — not always, but sometimes — that just our individual experiences as People of Color are political enough. And especially with everything going on now, I hope those attitudes towards The Joy Luck Club have shifted, because what that book explores rings true for so many people from immigrant families.

These criticisms were understandable at the time, only because of the paucity of AAPI writers who were being published when The Joy Luck Club came out. Some people mistakenly thought I was trying to represent all Asian culture, which wasn’t true. I’m very glad that Jamie [Redford] put that criticism in there, because it shows that my career as a published writer hasn’t always been filled with accolades. I think it’s good to have a discord when thinking about what needs to be out there, and what we need to do to encourage other writers to tell their stories.

But I do have to say that the criticisms that were leveled against me, mostly by male Asian writers, had to do with their feeling that my stories were about stereotypes, like the rape of a woman who is forced to become a concubine, and who later kills herself. That’s what happened to my grandmother. She was not a stereotype. I was writing these stories to discover things about myself through their lives — how my grandmother could not bear a life of condescension, and how having no choice led to anger, desperation, and ultimately killing herself. How my mother, who watched her die, became suicidal the rest of her life. And how they passed onto me — not the suicidal tendencies — but the absolute need to take control, to be in charge of my own choices and create my life, which is why I’m a writer. The people posing these criticisms wouldn’t know that my stories are based on my family history. They just see it as exotica. We don’t know the personal importance of a writer’s stories. But today, I’m glad there are many more AAPI writers out there, and their voices are there to speak about their own truths.

You’re also very involved in other arts, regardless if it directly relates to your writing. I want to talk a little about the Rock Bottom Remainders. What sort of catharsis did you find in singing that felt different from, let’s say, writing?

When I joined the band, I didn’t realize I had to sing. I know that sounds stupid, but I imagined that I’d just be dancing in costume or something. I was mortified when I found out I had to sing. But what I discovered about being in the band was that even if you’re terrified about trying something new, especially around other people, you can also bond over fear and survival. It’s like a near death experience.

I also discovered that performing, which I used to hate, is really about connecting with the audience. And that’s the key to performance. After the end of each performance, we’d always talk about the audience. That’s what performers do. You don’t always talk about how well someone sang or how you performed overall. You’re talking about who you’re performing for, and the energy of that specific crowd. Above all, there is a lot of camaraderie among the Remainders. We still perform occasionally. It is always a chance to deliberately not be serious, and to make fun of ourselves.

Who or what else are you reading these days?

Fiction wise, I’ve started Pachinko [by Min Jin Lee], and the non-fiction book I’m reading is The Human Swarm: How Our Societies Arise, Thrive, and Fall by Mark W. Moffett. He looks at both human and animal society, and how we are geared toward a failure in our social systems. Another book I’m reading is The Nesting Season by Bernd Heinrich, and it’s about what’s happening with our birds and their behavior when they’re courting, mating, nesting, and teaching their fledglings to fly and hunt, which I find fascinating. And sometimes when I want a little inspiration, I’ll read Sparrow Envy, which are poems by J. Drew Lanham, who is a naturalist and an ornithologist. I tend to read several books at a time in each genre, and it depends on my mood.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.