Books

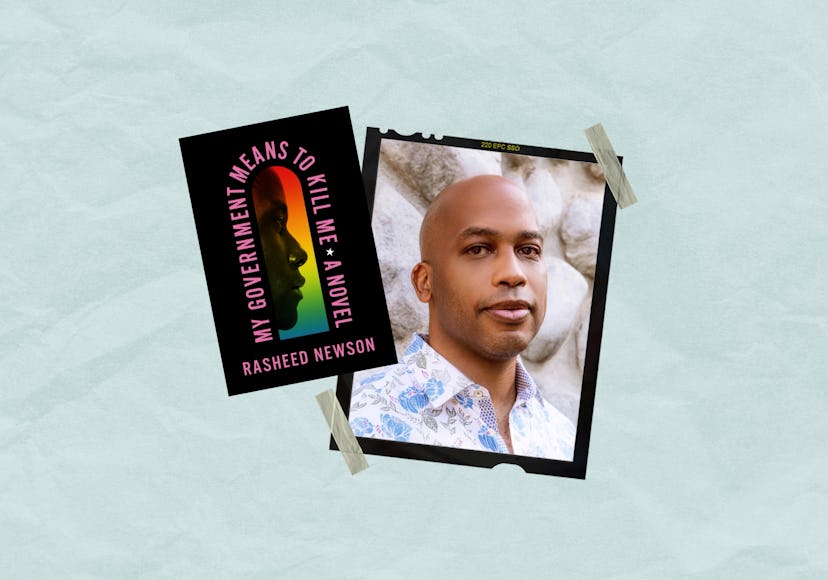

In His Debut Novel, Rasheed Newson Looks At Gay Life Amid The AIDS Crisis

Even during the epidemic, gay men in New York “still found ways to feel alive, young, and happy.”

It began as a thought experiment: “I’m Black and I’m gay, so I’ve spent my whole life wondering what I would have done had I been born during the civil rights movement, or what I would have done had I been 10 or 15 years older during the height of the AIDS crisis,” Rasheed Newson, the co-showrunner of Bel Air, tells Bustle. “If you took some of my personality traits and put them in a character [living in that time], what would that look like?” In writing My Government Means to Kill Me, he got to find out.

Newson’s debut novel follows Trey, a young, gay Black man from Indianapolis. In the summer of 1985, Trey casts both his six-figure inheritance and his college plans aside to pursue a Bohemian life in New York City, where he joins “a hidden society of Black sodomites” — namely, the Black gay men who gather at Harlem’s Mt. Morris Baths. It’s there that Trey strikes up a friendship with Bayard Rustin — the real-life activist and organizer who introduced Martin Luther King, Jr. to the concept of nonviolent protest — and finds himself thrust into activist circles.

The AIDS crisis serves as the backdrop for My Government Means to Kill Me, but Newson isn’t interested in telling a story about the gay community’s pain; although the novel doesn’t shy away from harsh realities, it devotes more time to the joy Trey finds in New York. “I think a lot of times when we do works of art about the AIDS epidemic, you would assume that no one laughed, you would assume that no one found any joy, that no one had any hot sex,” Newson says. “The truth is those things continue, no matter what we’re going through, and I don’t think they’re frivolous. I think they’re really beautiful. I think they’re signs of resilience. I think they’re signs of rebellion.”

Below, Newson discusses information overload, sex positivity in stories of the AIDS epidemic, and what he’s working on next.

To what extent do you consider this to be a plague novel?

I think of it as a coming-of-age novel happening during a plague. I wanted [the AIDS crisis] as a backdrop and a character who, while he was caught up in something very heavy, still found ways to feel alive, young, and happy.

I also wanted to write a novel that was sex-positive, to shake off the notion that people who have sex — even during the AIDS crisis — were promiscuous or stupid or bad. I don’t care what’s been going on in society. People have sex.

When I was in D.C., during college, I volunteered at this foster care center for children who were HIV positive and had AIDS. It’s called Grandma’s House. I would go there Friday night and volunteer. I’d help the paid caretakers, help the kids with dinner, homework, read them stories before bed. And I’d leave there around 9:00, 9:30, and get on my bike and go to Club Chaos, Badlands, or the Fireplace, and I would party and drink all night. I would hook up with guys and have sex.

There was nothing like being in a place where HIV and AIDS are front of mind, and then later that same night, maybe having unprotected sex. Those things happen, particularly when you’re young and feel invincible. I wanted to depict some of that dichotomy without attaching negative judgment to it.

And for Trey, the bathhouse feels like an escape from the outside world, like AIDS is something that exists outside of it.

Yeah, which is probably not technically true, but it’s how he feels. It is also his place of community. I think that can be lovely. I think that’s absolutely fine. If you’ve been ostracized for most of your life, you’ll take community wherever you can find it.

What do you think the AIDS crisis and the government’s failure to respond to it taught us about our society and institutions?

Unless an institution has a mission to look after you, it probably isn’t going to. If it’s not designed to see you, if it’s not designed to care about you, it won’t do that. We’ve had to build our own institutions, our own care facilities, our own clearing ground for information and services. That’s how you get things like the Gay Men’s Health Coalition.

That’s a lesson that’s stuck with us. Whether it’s Black Lives Matter or the gay rights movement, we don’t wait for some government agency to tell us what to do. We’re going to inform and help each other.

What surprised you the most when researching for the book?

It’s fascinating how fractious groups can be, even when they want the same thing. Again, I think over time and history, we smooth out those differences. Now, generally, people would say, “Yeah, we had to close the bathhouses because that’s where AIDS is being spread, and it was the responsible thing to do.” At the time, that was a fierce battle. If you wanted to reach the population that was most susceptible to contracting or spreading AIDS, it would have been smart to meet them in the bathhouses, where you could have provided condoms, information, and testing. But by shutting them down, you didn’t stop men from having sex with other men. You just pushed it into places we can’t track it. You put them into the woods. You put them into parked cars.

I wanted to revisit some of those arguments, because I think they’re healthy and more interesting than all the gay people against the Reagan administration.

Trey meets many real-life figures in the novel, including Bayard Rustin, Larry Kramer, and Dorothy Cotton. What made you want to use real people, as opposed to fictionalized versions of them?

[Laughs.] I didn’t want to use that many real people but the story led me there.

With Bayard Rustin, I thought, ‘Am I really going to put this guy in a sex club or a bathhouse?’ I decided to do it for two reasons. One is that I don’t think it besmirches anybody’s reputation to say they went to a bathhouse. Secondly, I came across the fact that Mr. Rustin had once been picked up for solicitation in Pasadena back in the 1960s. Cruising has been a part of being a gay man for a very long time, and I wanted to put that in the story.

Did you find it challenging or intimidating to — quite literally — put words into their mouths?

Yes! I mean, Larry Kramer was alive when I was writing this book. He was in his 80s, and I was scared like, “God, what if this comes out and he hates it and I get in trouble?”

But there is an incredible treasure trove of audio and video of these people. There’s a part [in the novel] where Rustin explains his thinking about being pushed out of Martin Luther King’s inner circle. I’m not imagining that. He gave that interview.

Do you have another book you’re working on?

I do. I want my next book to be about a Black, queer, gay man in LA, in an earlier time period. When we think of queer life in the 1950s or ’60s, we tend to think of small towns where it’s this shameful secret, whereas in Hollywood, it was an open secret. I won’t say it was all laughs and champagne, but [gay men living there] certainly had more liberties than we would normally think.

I’m interested in people who live in that glass closet and are happy to play that game — “I will take this female escort out to the movie premiere and then have these pool parties with young men” — and feel like that’s a great trade-off. [I want to] take that person and introduce political consciousness into that bubble.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

This article was originally published on