We often think of fairy tales as being idyllic and gentle, just as we believe childhood itself is. What we tend to forget as adults, though — in an era in which re-imaginings of classic stories are quite literally a dime a dozen — is that these stories are old. Really old. And as a result, the history behind certain fairy tales is often super creepy. Not that that’s a bad thing; on the contrary: Being able to confront things like death and cruelty in fairy tales is essential to our psychological development. But it’s worth remembering from time to time that just because something is a “fairy tale” doesn’t necessarily mean that it ends with everyone living happily ever after.

Of course, it can be difficult to trace the historical inspirations of tales that are this old; as such, a lot of what we’re dealing with here are theories, rather than confirmed fact. In many cases, though, the arguments are quite convincing — and even if the entirety of each story isn’t necessarily based on a historical event or person, it’s fascinating to look at how tiny kernels of truth may have made their way into the stories and legends that have become such key parts of our culture.

These six tales may very well all have historical precedent —and honestly, the history behind them is way freakier than anything you’ll find within the stories themselves.

1. The Pied Piper Of Hamelin

The story: A dude dressed in colorful clothing and carrying a pipe appears in a town suffering from a plague of rats and offers to rid the townspeople of their problem — for a price, of course. The mayor agrees. By playing infectious music on his pipe, the piper lures the rats away and into a nearby river, where they drown. The mayor then reneges on his agreement to pay the piper the fee he’d been promised — so the piper returns one day when all the adults are at church and plays his pipe again. This time, though, he lures the town’s children away. They’re never seen again.

The history: To be honest, we don’t totally know what happened in the town of Hamelin — but according to most historians, something did happen there prior to the 13th century that led to the birth of the Pied Piper tale. We’re pretty sure that whatever it was, it was traumatic. And we think it took out the town’s entire population of children.

Here’s how we know:

There was once a stained glass window in the church of Hamelin. It’s believed to have dated to around 1300; it reportedly contained the inscription, “In the year of 1284, on the day of John and Paul, it was the 26th of June came a colorful Piper to Hamelin and led 130 children away,” although sadly it was destroyed in 1660. There’s also the Lueneburg Manuscript, which is dated 1440 – 50 and reads, “In the year of 1284, on the day of Saints John and Paul on June 26, by a piper, clothed in many kinds of colours, 130 children born in Hamelin were seduced, and lost at the place of execution near the koppen.”

The figure of the pied piper is believed to be a personification of forces the people of Hamelin couldn’t otherwise comprehend — their way of making sense of something huge and tragic and of great enormity.

2. Bluebeard

The story: The powerful and wealthy Bluebeard has been married several times, only to have his lovely wife go missing each time — until he finally meets his match. He goes to a neighbor, asks to marry one of the neighbor’s daughters, and takes the young woman to wife. One day, though, he tells his wife he has to go on a business trip and leaves her the keys to their glorious chateau. She can open any door — except one. There is one that she is not to touch, under any circumstances.

She opens it, of course — and finds inside the decaying remains of each of Bluebeard’s previous wives. Through trickery, however, she and her siblings band together and kill Bluebeard, leaving her an independently wealthy widow. She and her siblings all marry people they love and live happily ever after.

The history: There are a lot of different versions of this tale in a variety of different countries and cultures; you might, for example, be more familiar with the Grimms’ version, “The Robber Bridegroom,” with its repeating refrain of, “Be bold, be bold, but not too bold, less that your heart’s blood should run cold.” However, “Bluebeard” is the French version, and as such, it’s got some particular inspirations.

One is Conomor, known as Conomor the Cursed, an early medieval ruler of Brittany. We don’t know a ton about him — indeed, he’s as much a party of legend himself as he is of history — but he was likely a tyrant; what’s more, one legend clinging to him has a few key similarities with Bluebeard: A woman named Trephine agrees to marry him in order to stop him from invading her father’s lands — and one day when her barbarous husband is away, she finds a room containing the remains of Conomor’s three previous wives. After she prays for them, their ghosts appear and tell her that if she becomes pregnant, Conomor will kill her — his ire has something to do with a prophecy that he’ll be killed by his own son (so, now we’re also kind of getting into Oedipus territory). She does get pregnant, so she runs away; although she does manage to give birth before Conomor finds her, find her he does and immediately beheads her. She’s restored to life by a saint, but after she dies of natural causes, Conomor finds her son and kills him, too.

The second source of inspiration is Gilles de Rais, a former military leader who fought beside Joan of Arc and was later accused and convicted of murdering dozens of children who went missing in the Nantes countryside in the 15th century. He was executed in 1440, although recently there’s been a move to exonerate him; the argument is that the evidence simply wasn’t there for the conviction.

Charles Perrault was fascinated by these two figures — particularly Gilles de Rais (because, y’know, France) — and is believed to have taken his inspiration from them for the 1697 version of “Bluebeard” published in Histoires Ou Contes du Temps Passé.

3. Snow White

The story: Beautiful girl, evil queen/stepmother, seven dwarfs, poison apple, prince, magical kiss, you know the deal. Fun fact: At the end of the Grimms’ version, the evil queen is forced into a pair of red hot shoes and made to dance in them until she falls down dead.

The history: I should preface this one with a disclaimer: It’s really only a theory, and it’s got some holes in it. But for the curious, there currently two candidates vying for the title of Possible Real Life Inspiration Of “Snow White” — both of whom, curiously, are named Margaret.

Let’s talk about Margaretha von Waldeck first. In 1994, German historian Eckhard Sander published a work called Schneewittchen: Marchen oder Wahrheit?, which translates to Snow White: Is It a Fairy Tale? Sander claimed that a German countess born to Philip IV in 1533, Margartha von Waldeck, was the basis of “Snow White”: It seems Margaretha’s stepmother, Katharina of Hatzfeld, wasn’t terribly fond of her and forced to her move to Brussels when she was a teenager, where she met and fell in love with Phillip II of Spain. However, her father and stepmother weren’t wild about this development, either… and then Margaretha suddenly died without warning at the age of 21, thereby solving her parents' problem. The theory is that she was poisoned.

Sander also points to inspirations for the dwarves (children whose growth had been stunted working in Margaretha’s father’s copper mines) and poison apple (an incident in German history where a man retaliated against kids stealing his fruit by giving the tykes poison apples — kind of like a notable American urban legend I could name).

Then there’s Maria Sophia Margaretha Catharina Freifräulein von Erthal. According to one group of researchers in Lohr, Bavaria, this noblewoman, who was born in 1729, might also have inspired the “Snow White” tale. Maria’s father, Prince Philipp Cristoph von Erthal, is said to have given a mirror to his second wife as a gift — and this second wife appeared not to like Maria overmuch, making her life quite difficult indeed. Said Dr. Karlheinz Bartels according to Mental Floss, “Presumably the hard reality of life for Maria Sophia under this woman was recast as a fairy story by the Brothers Grimm.” Like the Margartha theory, this one posits that the seven dwarfs are an interpretation of mine workers in the region — this time being not children, but men of very small stature.

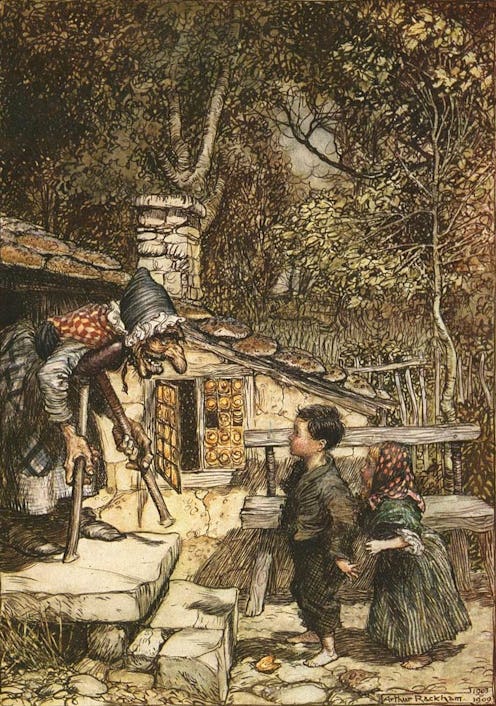

4. Hansel and Gretel

The story: Hansel and Gretel, a brother and sister, live together with their parents in a cottage in the forest. Although their father, a woodcutter, is kind, he’s kind of spineless, so when his cruel wife tells him that in order for them to survive a famine, they’ve got to abandon the kids in the woods, he does so. The kids find their way home a few times, thanks Hansel’s cleverness; once, though, he tries to mark their path with breadcrumbs, rather than stones, and finds that the crumbs have been eaten up by birds, which results in the children getting lost.

Eventually the stumble upon a cottage made of gingerbread, where a seemingly kindly old woman offers to feed them — but it’s a trap. She forces Gretel to do her drudgery, and she starts fattening Hansel up so she can eat him. The kids eventually trick her, though, pushing her into her own oven and cooking her alive. They steal all her valuables and head home, where they discover their mother has died. They live happily ever after with their dad.

The history: Again, this one is more a theory than a fact, but it’s believed that the themes of "Hansel and Gretel" have their roots in two elements of German history. First, as SurLaLune Fairy Tales notes, Maria Tater’s Off With Their Head!: Fairy Tales and the Culture of Childhood points out that child abandonment and infanticide were not unheard of as ways for families living in poverty to cope with their situations; indeed, the practices were still going on in the 19th century, when the Brothers Grimm were collecting the folktales they’d later publish.

It’s also possible that the Great Famine, which struck Europe between 1315 and 1317, had something to do with “Hansel and Gretel.” Again, child abandonment and infanticide occurred with some frequency during this period; everyone was starving, after all. That’s the setup for “Hansel and Gretel,” so it’s not out of the question that it may have been an inspiration for it.

5. Rapunzel

The story: When Rapunzel’s mother is pregnant with her, she has the worst pregnancy cravings ever for the green for which the little girl will eventually be named — which, as luck would have it, grows bountifully in the garden of the witch next door. She convinces her husband to steal some for her; however, the witch catches him. She says he can have all the rapunzel he wants if he’ll give her the baby when it’s born. He agrees to the trade.

When Rapunzel turns 12, the witch — who she believes is her mother — shuts her up in a tower to protect her from the outside world (read: MEN). The only way into the tower is to climb Rapunzel’s impossibly long hair. Eventually a prince wandering the woods finds her, climbs up her hair, and falls in love with her/asks her to marry him/has sex with her/all of the above, depending on which version you’re reading. They plan her escape, but the witch finds out, cuts off Rapunzel’s hair, exiles her, and tricks the prince into climbing the hair that is no longer actually attached to Rapunzel’s head before tossing him to a patch of briars below, blinding him.

While wandering the wasteland, Rapunzel gives birth to twins. The blind prince eventually finds her and identifies her by her voice. Her tears restore his sight, they return to his kingdom, and they live happily ever after.

The history: Saint Barbara, an early Christian Greek saint and martyr (who, to be fair, may or may not be mythical), is believed to have been an inspiration for at least part of the Rapunzel tale. The history is a little patchy, but we think she lived in either what’s now Turkey or Lebanon in the third century. Her father allegedly locked her in a tower to protect her (sound familiar?) — but not necessarily from men; he was more concerned about her coming in contact with Christianity, because he was pagan himself. She found Christianity anyway, though, and although she did manage to escape her father before he killed her, she was later caught, tortured, and beheaded. She’s the patron saint of armorers, artillerymen, military engineers, miners, people who work with explosives, and mathematicians.

6. Beauty and the Beast

The story: A merchant with a huge family going through a tough time seeks shelter during a terrible storm. A beautiful palace opens its doors to him, feeds him, and allows him to rest. In the morning, before he leaves, he spots a rose garden and takes a flower to give to Beauty, his youngest child (and also objectively the “best” one — she’s smart, beautiful, and kind, whereas the merchant’s other kids are jerks) — but when he does so, he’s caught by a “Beast,” who tells him that because he stole a rose after accepting his hospitality, he must die. However, they strike a bargain: The merchant can go free if one of his daughters returns.

Beauty goes, because she is kind and good, and she is welcomed with open arms. Her life is honestly pretty fantastic, but she gets homesick and asks if she can go visit her family. The “Beast” agrees on the condition that she return in one weeks’ time. She goes, and her sisters are super jealous of the beautiful clothing she’s wearing and keep trying to convince her to stay longer than a week so they can ride her thunder. She relents — and then she discovers via a magic mirror that the “Beast” is dying because she didn’t return to him.

She’s horrified and goes back, crying over him when she believes that she’s too late to save him. At her tears, he transforms into a human, revealing that he had been under a curse; their love broke the curse, and now they can live happily ever after.

The history: This one is creepy not because of the existence of the “Beast,” but because of how he was treated during his early life — that is, we’re looking at the horrors of humanity’s own cruelty. Awesome.

Petrus Gonsalvus was born in 1537 on Tenerife, the largest of the Canary Islands. He had hypertrichosis, which resulted in thick hair growing all over his body. Then, as now, people who were visibly “different” were often treated as oddities or curios; Gonsalvus, for example, was captured and kept as a “wild man,” being forced to live in an iron cage and fed raw meat and animal feed.

People are the worst.

In 1547, though, when Gonsalvus was 10 years old, he was gifted (yes, gifted — again, people are the worst) to King Henry II of France. It turned out to be fortuitous: Henry did not think that Gonsalvus was a wild animal and chose to educate him as a nobleman — he learned not only to speak, read, and write, but to do so in three different languages. (I mean, Henry still wasn’t great — and his wife, Catherine de Medici, looked at Gonsalvus as an “experiment” more than anything else — but at least he wasn’t being forced to live in a cage anymore.) After Henry’s death, Catherine de Medici married Gonsalvus off to another Catherine, the daughter of a court servant. They were married for more than 40 years and had seven kids together.

We’re fairly certain that Petrus Gonsalvus’ life inspired French novelist Gabrielle-Suzanne Barbot de Villeneuve to write “Beauty and the Beast,” which was published in 1740 in LaJeune Américaine et les Contes Marins.

There are far more fairy tales than just these out there, of course, and a lot more horrifying history. But I think it's worth remembering that this is where it all comes from: Ourselves. The monsters of real life? They're usually us.