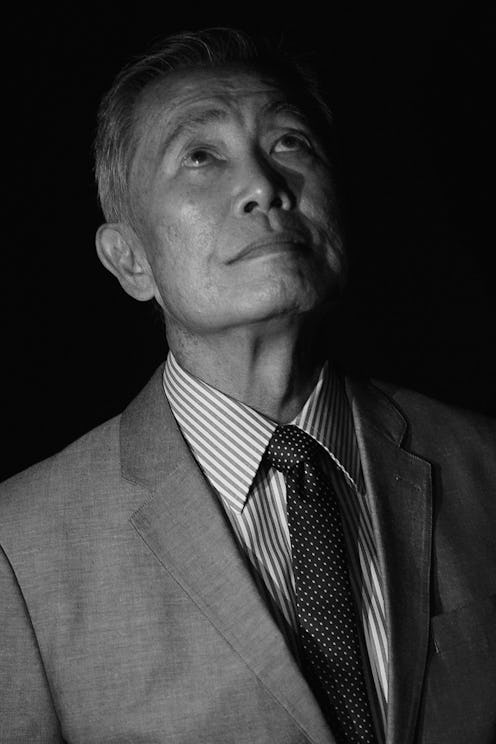

There’s no getting around it: Election night was rough. More than rough — it was what I would argue will be remembered as one of the darkest moments in American democracy. But George Takei’s election night message, which he shared across his social media platforms, does what so many of us need right now: It reminds us that there is still hope. That we’ve gotten through terrible things before, and that we will get through this terrible thing, too. And that the key to doing so is caring about each other, treating each other kindly, and working together.

Takei, whose Twitter bio is perhaps the most accurate and poignant one I’ve ever seen — he describes himself as, “Some know me as Mr. Sulu from Star Trek, but I hope all know me as a believer in, and a fighter for, the equality and dignity of all human beings” — launched a series of seven tweets out starting at 12:46 a.m. EST. As a Trump presidency grew more and more likely over the course of the night, Takei began by addressing “all who voted to defeat Donald Trump and what he represents” — noting that “we may have not prevailed, but we must not despair.”

He continues by affirming how so many of us feel; however, he also reminds us what we can do in response, urging us to action:

Because even if the country we see when we look around us isn't the country we had hoped for, we know what it is we want to see:

We've been through much, all of us, no matter how we got here...

...And no matter what things look like right now, it doesn't mean we've stopped fighting:

I’ll be honest: I’m not feeling terribly hopeful myself at the moment. At 11:15 p.m. EST during election night, I had to step away from my computer for a few minutes because I was crying too hard to do my job. By the time the Associated Press announced that Donald Trump had won the presidential election at 2:31 a.m. on Nov. 9, I thought I had gotten to the point where I was mostly numb; however, then I started to cry again. I cried again as soon as I woke up this morning, and every time I think I have it under control, I start up yet again, because right now, all I feel is despair knowing that this is the country we now live in. I am more frightened now than I have ever been before.

I realize that this fear is, in and of itself, a privilege; as a mostly white, straight, cisgender person who grew up in an upper-middle class household and got a terrific education without accruing astronomical debt, I am one of the most privileged types of people that exist in the United States. I am also a woman, though, so I’m not the most privileged variety of American; that… well, I’m not sure I’d call it an honor, but whatever it is, it goes to white, straight, cisgender, generally wealthy men. But although this country has always and continues to be routinely unsafe for so many people — LGBTQ people, people of color, immigrants, people with disabilities, women, and so many more — I have been stupidly lucky that generally, I have felt, and indeed been, mostly safe for most of my life.

And maybe my awareness of this sense of safety is that much stronger because history tells me that, had I been born a few decades earlier, it all would have gone much, much differently.

Takei has written, spoken, and performed at length about his family’s incarceration in internment camps in the United States during the Second World War. In 1942, when Takei was 5 years old, he and his family were sent first to the converted horse stables in Santa Anita Park, then to the Rohwer War Relocation Center in Arkansas, and finally to the Tule Lake War Relocation Center in California. He was 8 years old when they were released. Said Takei in a 2014 interview with Democracy Now! of those years:

When we arrived at Rohwer, in the swamps of Arkansas, there were these barb wire fences and sentry towers. But children are amazingly adaptable. And so, the barb wire fence became no more intimidating than a chain link fence around a school playground. And the sentry towers were just part of the landscape. We adjusted to lining up three times a day to eat lousy food in a noisy mess hall. And at school, we began every school day with the Pledge of Allegiance to the flag. I could see the barb wire fence and the sentry towers right outside my schoolhouse window as I recited the words "with liberty and justice for all," an innocent child unaware of the irony.

When his family was released, Takei said, “We lost everything. We were given a one-way ticket to wherever in the United States we wanted to go to, plus $20.” They were denied housing; only other Asian people would hire the family; they lived on skid row. Said Takei, “My baby sister, who was now five years old, said, ‘Mama, let's go back home,’ meaning behind those barb wire fences. We had adjusted to that. And coming home was a horrific, traumatic experience for us kids.”

So, remember that thing where I said I was mostly white? That’s true. I look white — something which, again, has afforded me a considerable amount of privilege; because I read as white, my experience in this country has been that of a white woman — but I’m multi-racial. My father is Japanese, and had our family been alive and living on the Pacific Coast of the United States during World War II, it's likely we would have been rounded up and put into the internment camps, too.

This often seems like a far-away thought, but right now, it’s hitting me harder than it ever has before. Because although my family and I may not be in any danger of being in that position now — anti-Asian sentiment is no longer what it was during WWII — the reality is that many other people and families living in this country might be.

As Takei has pointed out, Trump’s rhetoric — the idea of walls, of bans on entire religious groups, of describing immigrants as “rapists” — is the type of rhetoric that leads to things like internment camps. Indeed, Trump even said in an interview with TIME Magazine that he might have actually supported internment camps, had he been around and conscious then. (Trump was born in 1946. After this comment, Takei responded in a Facebook video by inviting him to Allegiance, Takei’s Broadway musical about his family’s experiences so he could actually see what it was like, safely from a seat.)

There have been too many “How is this 2016?!” moments to count during this election cycle, but this is perhaps one of the most WTF of them: That a candidate who has literally said that he might have supported a racist, fear-mongering policy from over 70 years ago, and whose standpoint on other groups of people sound exactly like that racist, fear-mongering policy from 70 years ago could not only become the major party nominee, but actually become the president-elect, should be unthinkable.

And yet, here we are. And I am so scared for so many people, and so sorry our country has failed you so utterly.

This is where Takei’s social media message comes back into the picture. He is right that we have seen wars and grave injustices and slavery and civil wars. And when we look back on our history, we are not proud of these things. But we did find our way through, and so I have to hope that, as he says, we will now, too. We may not be ready to fight right away; many of us need to mourn right now, and we need to take care of ourselves and each other. But when we are ready, it will be time to fight — to build, as Takei says, “the society we wish to live in.” And to start, we can hold our loved ones tight, and tell them how much we love and support them, and, in Takei’s words, “Tell them that it is in times of sadness and in the toughest of days where we often find our true mettle.”

And that mettle is strong AF.