TV & Movies

Vacations Are A Nightmare

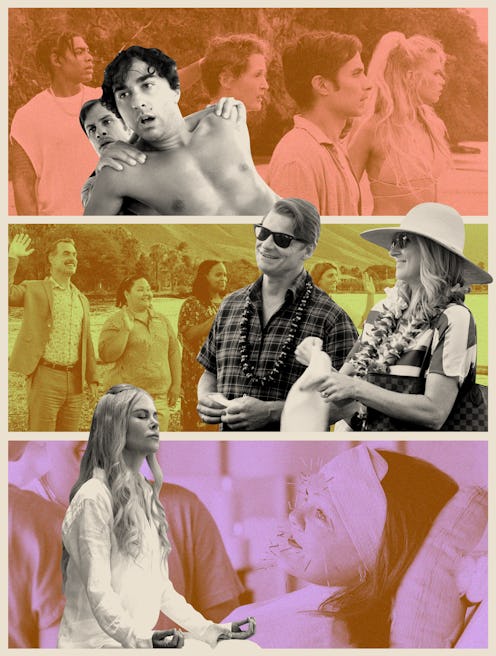

The White Lotus, Old, and Nine Perfect Strangers all feature rich people on disastrous trips that feel oddly representative of our hellish year.

In October 2020, Kim Kardashian uploaded a series of photos to Instagram showing off her lavish 40th birthday celebration on a private island. It was seven months into the global pandemic, and many of her followers were still mostly confined to their homes. Kardashian’s caption about health screens and quarantines weakly attempted to minimize the outrage, but the damage was done. What was to her a nice gift to her family and friends was to the rest of us an example of blind privilege: amid the pandemic, a “safe” vacation was a luxury that only the exorbitantly wealthy could afford.

It seems like no coincidence, then, that this summer’s pop culture conversation has been dominated by shows and movies about rich people’s vacations going awry. In Hulu’s miniseries Nine Perfect Strangers, guests arrive at an exclusive wellness retreat hoping for a quick reset only to find the treatment program is centered around “suffering.” The tropical getaway in M. Night Shyamalan’s thriller Old turns existentially dark when a group of travelers gets trapped on a beach that supernaturally ages them. And HBO’s satirical dramedy The White Lotus follows a group of VIPs at a Hawaiian resort whose high demands cause escalating conflict and, ultimately, death.

In a time when class divisions have widened to new extremes, there’s a delicious catharsis in watching a wealthy, privileged man-child throw a tantrum over the missing amenities in his hotel room or an influencer be forced to give up her phone. But the popularity of these stories is about more than schadenfreude: In each one, fears about the current state of the world teem below the surface. The White Lotus includes a side plot about an Indigenous hotel worker's ill-advised attempt to seek retribution for years of colonialist tourism that robbed his family of their land. Nine Perfect Strangers weaponizes a major symbol of wellness culture — the smoothie — in a way that makes the resort guests think twice about blindly trusting the healing powers promised by its mysterious guru. And Old mines an entire lifetime of data collection for a nefarious big pharma scheme.

This all hits harder against the backdrop of a global health crisis. The pandemic has only made us more reliant on medical companies like the one in Old to manufacture a safe and effective vaccine — and brewed plenty of distrust in them. The guests on Nine Perfect Strangers make increasingly risky attempts to assuage their sadness, not unlike the rest of us contending with rising rates of depression and anxiety. And a White Lotus employee is killed after being pushed to their limits by an entitled patron, which, after a year of watching service workers be maligned and abused for trying to enforce COVID guidelines, doesn't feel like as big of a leap as it once might’ve.

Though these stories unfold in exotic destinations, each is set in a fixed location the characters can’t leave, mirroring the isolation and resulting challenges society has endured for the past 18 months (all three productions shot at a single location due to Covid safety protocols). Secluded together in their own posh versions of quarantine, they must all contend with individual and collective tragedy while mitigating clashing personalities. Each story feels like a social experiment, where the constraints of the beach or resort act as a test of character: Faced with adversity or even simply cabin fever, some people bond and fight to take care of each other; others respond violently and cling further to their individualism. “We will make destructive decisions if we don’t feel safe with each other,” a psychologist trapped on the beach in Old warns early on.

There are times in each story when it seems like the characters may be able to detangle the messiness of their lives or find a way out of their luxurious prison. But there is an undeniable pessimism in watching them crumble beneath their circumstances that feels sharply attuned to our own cynicism about facing the world’s current host of issues. We can’t outrun our problems, even in paradise.

This article was originally published on