Books

These 2 New True Crime Books Have Plotlines That Go WAY Beyond Unsolved Murders

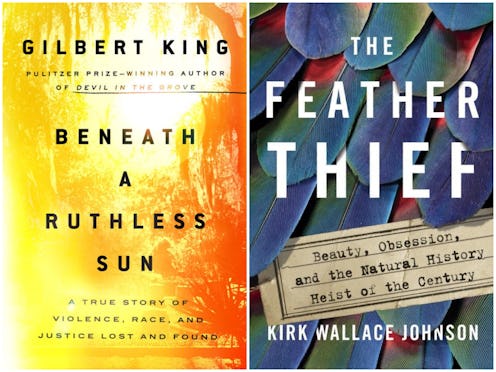

Until NPR’s hit podcast Serial debuted in 2014, the true crime genre was a guilty pleasure many indulged in, but few would admit to out loud for fear of being ousted as simple, or worse, insensitive. For years, detractors of the genre criticized it for being distasteful, disrespectful, voyeuristic, or even immoral. But now, with the rise of both the popularity and the quality of true crime in every form, from weekly podcasts and bestselling books to television anthologies and prestige series, the genre is finally starting to earn a certain level of respectability, and even some critical acclaim. Two new books out this week — Kirk Wallace Johnson’s The Feather Thief and Gilbert King’s Beneath a Ruthless Sun — are perfect examples of what kind of cultural insight, historical understanding, and good old-fashioned entertainment the newly invigorated world of true crime literature has to offer even the most skeptical readers.

In the year 2018, it’s no secret that Americans are obsessed with true crime. We compulsively listen to creepy podcasts like My Favorite Murder, binge watch foreboding series like The Staircase, and tune in every week to see real-life horror come to life on shows like Cold Case Files and Dateline NBC. When it comes to the book world, though, true crime has long been swept to the margins to make way for more “respectable” writing. There are, of course, the occasional bright stars: Truman Capote’s In Cold Blood and Erik Larson’s The Devil in the White City were both published, nearly 40 years apart, to critical acclaim, but they are just two of a handful of exceptions within a genre that has rarely been taken seriously. For years, true crime readers have been deemed unsophisticated while the its writers have been labeled opportunistic or even exploitative. How can an author in good conscience make money from someone else’s tragedy, critics of the genre have long asked, and how can its consumers find enjoyment in another’s pain?

There are a lot of reasons why we seek out true crime stories. Americans have always been fascinated with grisly tales of murder and mayhem, whether they be in the tabloid pages of the early 20th century papers or on our Netflix accounts today, and our appetite for them has only grown in recent years. Now more than ever, we openly and unapologetically seek out true crime to scratch that morbid itch only real life tragedy can, to satisfy our cravings, however dark, for violence. We want to bear witness to criminal activity, to be a part of the danger, to come close to death without meeting it, but more than that, we want to uncover some kind of truth, hence the genre’s name. It may be the notion or murder or the promise of mystery that draw us into true crime, but it’s the opportunity to uncover some kind of answer that keeps us rooting around in the darkness.

That is what has propelled Michelle McNamara's I'll Be Gone in the Dark to the top of the New York Times bestseller list. Throughout her remarkable book, which was posthumously published following her death in 2016, the true crime buff's relentless search for the man behind the Golden State Killer's mask keeps readers turning the pages, desperately hoping McNamara has been able to do what so many others haven't: solve the crime. It is also what makes Alexandra Marzano-Lesnevich's murder-memoir, The Fact of a Body, so irresistible. Not only does the author's account pull readers into the true story of convicted child murderer Ricky Langley, but it forces them to examine the parallels between the life of a monster and that of a regular girl, and it encourages them ask tough questions about morality and the value of a human life. That is what the best contemporary true crime is doing — using the previously disregarded genre to explore our history, culture, politics, and even ourselves — and McNamara and Marzano-Lesnevich are far from the only ones.

With The Hot One, author Carolyn Murnick uses the tragedy of her best friend's murder to explore female friendship, womanhood, and America's culture of slut-shaming and victim blaming. In The Manson Women and Me, award-winning journalist Nikki Meredith tries to find out what it takes to drive "normal" people like Leslie Van Houten and Patricia Krenwinkel to commit horrible acts of violence. Unlike the countless true crime books about the Manson murder before it, Meredith's thoughtful account provides a valuable insight into the minds of two young women who are presented, for the first time, and fully formed human beings. In each of these books, the authors are driven by a a desire even bigger than curiosity, fame, or even money. They are compelled forward in their research and their storytelling by an insatiable desire to uncover the truth and tease out the answers to some of life's most difficult questions.

In Beneath the Ruthless Sun, Pulitzer Prize-winning author Gilbert King is trying to do just that. Through his exploration of a crime committed in one small Florida town over 60 years ago, he strikes at the heart of questions of race, justice, privilege, and corruption that have long been left unanswered. In doing so, his latest work — much like his previous and highly acclaimed book, Devil in the Grove — proves that, in the right hands, true crime stories aren’t just cash grabs. They can be forms of literary activism.

Beneath a Ruthless Sun: A True Story of Violence, Race, and Justice Lost and Found by Gilbert King, $25, Amazon

Beneath the Ruthless Sun begins with a story of a rape committed in December 1957. The victim, a prominent wife of a Florida citrus baron, tells authorities a “husky Negro” was responsible for her attack, and within hours, Lake County’s infamous sheriff and supposed KKK leader Willis McCall rounds up and arrests “virtually every young black male in the neighborhood.” After holding two of his alleged suspects in prison for two days without any contact with the outside world, McCall surprises virtually everyone in the community and lets them go, and instead charges Jesse Daniels with the crime. A poor, 19-year-old, mentally impaired white kid who many in Okahumpka knew as simply “the boy on the bike,” Jesse is obviously not the true culprit of the crime, and yet, he finds himself locked up in a state mental institution without trial. It seems all hope was lost — that is, until Mabel Norris Reese, the editor of a local weekly paper and self-proclaimed nemesis of McCall, gets wind of the story and refuses to let it go until true justice is served.

For years, the intrepid journalist tries to uncover the truth about Jesse’s arrest and discover who is being protected, what is being covered up, and just how deep the corruption goes — a truly fascinating journey King recounts in page-turning detail. A brilliant and heavily researched work, Beneath the Ruthless Sun takes readers along for a wild and thought-provoking ride towards truth and justice. Along the way, it not only tells the captivating story of a true crime, but it takes a deep dive into the very issues at its core: sex, race, class, mental health, and official corruption. Like the best books about the wrongfully convicted, it also makes a compelling argument for criminal justice reform, and perhaps an even more important argument for examining our country’s dark past as a way to build a brighter future.

The Feather Thief: Beauty, Obsession, and the Natural History Heist of the Century by Kirk Wallace Johnson, $18, Amazon

Author Kirk Wallace Johnson peers into the past, too, with his latest true crime book, which doubles as a enthralling exploration of human’s desire to possess beauty and control the natural world. In The Feather Thief, the celebrated journalist recounts the remarkable story of Edwin Rist, an American musician who broke into the British Natural History Museum in 2009 and made off with nearly 300 rare bird skins. Among them were dozens of priceless samples collected over 150 years earlier by Alfred Russel Wallace, a naturalist and contemporary of Darwin whose breathtaking discoveries helped establish the field of geobiology. After hearing about the “feather thief” on a fly-fishing trip, Johnson becomes obsessed with the bizarre story, and quickly finds himself immersed in the feather underground. In engrossing detail and with the skill of a truly talented storyteller, Johnson takes readers on his journey through “a world of fanatical fly-tiers and plume peddlers, coke heads and big game hunters, ex-detectives and shady dentists.” He also sends them hurtling back in time, to the very jungles where Wallace collected the incredible specimens that Rist, a century and a half later, risked everything to steal.

A riveting story about mankind’s undeniable desire to own nature’s beauty and a spellbinding examination of obsession, greed, and justice, The Feather Thief proves not all thrilling true crime has to involve murder, rape, or the exploitation of victimhood. It's story is a gripping page-turner that leads readers on a decades-long wild goose chase — er, wild bird chase — no guts and goriness required.