Life

So You've Messed Up: Recognising Failures In Your Anti-Racism & What To Do Next

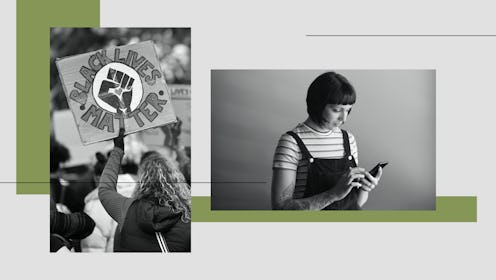

In the past weeks, following the death of George Floyd at the hands of Minneapolis police, thousands of people around the world have joined demonstrations and flooded social media with shows of support for the Black community. As part of this, many are being called out publicly for past and present behaviour, while others are privately reflecting and reassessing. How to recognise your own mistakes to become a better anti-racist ally will require work.

While online activism is important, doing the work offline is also crucial for real change. For many, that will need to begin with self-education about white supremacy and the racist systems it creates and perpetuates. Racism is embedded within our social and political system, and can manifest in both subtle and more obvious ways – there’s a lot to learn.

It is without question a significant time for civil rights, inspiring communities to do more to support Black Lives Matter and related movements, in the call for an end to systemic racism. It’s a learning process, and there’s a lot that’s likely to come up. Here, we work through how to be a better anti-racist ally, what to look out for, and how to right those wrongs.

Recognise the difference between optical allyship & activism

So you posted a black square on Instagram for #BlackoutTuesday, and you’ve taken to social media to show your support for Black Lives Matter and condemn the actions of Minneapolis police officers – you’ve done your bit, right? Wrong.

Unless you’re taking more tangible actions offline too, these displays of support are all examples of “Optical Allyship” – the term coined by Latham Thomas, founder of Mama Glow and author of Own Your Glow. In an Instagram post on May 1, Thomas defined this as “allyship that only serves at the surface level to platform the ‘ally’, it makes a statement but doesn’t go beneath the surface and is not aimed at breaking away from the systems of power that oppress.” Essentially, it’s performative.

As Holiday Phillips writes in Forge: “The problem with performative allyship is not that it in itself damages, but that it excuses. It excuses privileged people from making the personal sacrifices necessary to touch the depth of the systemic issues it claims to address.”

Ensuring you are actively anti-racist, and a non-optical ally, will take research and self-education, plus putting these learnings into practice day to day. So, that said, what are you doing offline, when nobody is looking?

“If, on reflection, everything you do is public,” Phillips says, “it’s likely you’re a performative ally.” She suggests, instead, doing “something that no one will ever know”. Challenge yourself to do things quietly, such as addressing your buying habits and supply chains, confronting practises within your workplace, and calling out racist remarks when they happen. “That way, you know you’re really down for the cause — and not the cause of looking like a woke person.”

Speak to people in your life about issues around race & racism

It would be a mistake to believe that the anti-racism work stops at you. Establishing allyship means addressing the unconscious bias in your community, too, by challenging friends, family and colleagues. It is important here to note that this responsibility does not lie with BIPOC friends, family and colleagues. If white people truly want to make a difference, it’s key to speak to each other about complicity and call it out.

To those who express hopelessness and “what’s-the-point”-ism, with an attitude that implies nothing will ever change, it's important to address their standpoint. As Robin DiAngelo states in a reading guide for her book White Fragility: Why It's So Hard for White People to Talk About Racism: “The perception that nothing can be done often keeps the existing system in place.” In response to in-activism, suggest action; whether reading up, petitioning, donating or protesting.

DiAngelo also suggests a series of sentence openers, or “silence breakers”, to address two common obstacles in the discussion of racism: the fear of making a mistake, and the lack of humility. For example, asking “Can you help me understand whether what I’m thinking right now might be problematic?” sets up a dialogue which is open to mistakes, but looking to resolve them, too.

As Phillips explains: “It’s easy to call people out when you’re hidden behind a keyboard.” You know what’s hard? Calling out your boss when he routinely mixes up your two Indian colleagues, or facing off with your racist relative when they start talking about “immigrants taking our jobs”. If you don’t feel confident enough yet to speak up, that’s also okay, recognise it and commit to working on it so that, one day soon, you can.

Tips for speaking to people in your life about race & racism:

- Call people out in person, including friends, family or in the workplace.

- Share your own mistakes, it helps to normalise personal growth.

- Know that it might be awkward or uncomfortable in the moment, but the message you are communicating is more important than how you might feel.

- Tell a story about how your privilege has protected you, sharing your own recognition of privilege can help others recognise it within themselves.

- “Why do you think that is?” can be just as impactful as sharing multiple facts and figures about a systemic bias. It makes people think beyond the stats.

How to respond if you are called out for problematic behaviour

Don’t become defensive

First things first: don’t become defensive. Being called out can be a clear identifier of intrinsic and unconscious bias in your own life, so take time to think it over before responding. Pushing back will make the situation unnecessarily heightened, especially for the person who stepped up to point out the issue.

Denial and defence mechanisms, in order to avoid accountability or avoid feeling guilty, can quickly turn into racial gaslighting. Learn the forms that gaslighting can take; it's not always as straightforward as you might think. Phrases such as “calm down” and “in my opinion, it isn’t racist” inherently contradict the validity of what you are being called out for, discounting the view of others.

It’s important to accept that you might not always get it right. On last week’s Newsnight (June 1), George the Poet, full name George Mpanga, refuted seasoned journalist and presenter Emily Maitlis’s suggestion that racism in Britain is not “on the same footing” as it is in America. “Our police aren’t armed, they don’t have guns, the legacy of slavery is not the same,” Maitlis said.

“When you talk about the history of race relations, you have to consider the role of the British Empire on the African continent and the political and economic consequences of that interaction,” Mpanga replied. “I hope this is a learning point for many people who think along the lines that you just expressed, that this is an American and not a British issue.”

Listen, in order to learn

Listening is, of course, crucial for non-optical allyship. Knowing when to stay silent, creating space for marginalised groups to speak, is part of the learning curve. If you’re a non-Black ally, your ability to self-educate on the matter is, in itself, a privilege. As makeup artist Sir John succinctly explains on Instagram: “It is a privilege to educate yourself about racism instead of experiencing it.”

Listen to those around you who have experienced racism first-hand, and don’t immediately make the conversation about you/your friend/your aunt’s neighbour. While trying to relate and empathise with personal stories may be well intentioned, now is not the time. Leave the mic with them, learn from their lived experience. And if it makes you feel uncomfortable, sit with it, that feeling is important.

Question & educate yourself

Interrogating your own actions is key to making positive change. Why did you respond that way? Why do you feel like this? What could you have done differently? Asking these questions will help to address the steps you need to take. A good place to start is by educating yourself about racism in Britain and getting to know the Black British experience. (There are books about race you can read, Instagram accounts you can follow, UK organisations you can support, and podcasts you can listen to to further your personal learning on the subject).

Learning from and recognising where you, and those around you, have gone wrong – and accepting that this is bound to happen along the way – can help avoid repeating the same mistakes in the future. Educate yourself, use your privilege to amplify Black and POC voices, challenge yourself to unpack your own systemic issues and stereotypes, and call for others to do the same. Most importantly, don’t do nothing. As Barack Obama wrote: “Sustain the momentum by channeling [your] energy into concrete action.”

This article was originally published on